| |||||||

|

Bows and Wheels new and old bowing technologies |

|

|

The bow you are listening to on this page is the interactive the k-bow in combination with my tenor violin. I'm manipulating (with the left hand) the pitch side of the equation very little; most of what you are hearing is actualised by bow techniques. Sensors measure the bow speeds, starts and stops, bow positions relative to bridge and tilt, bow hair pressure, and the parts of the bow used from frog to tip. These movements are converted into MIDI information which then transforms the actual sound of the tenor violin in real time. There is no sampling used in this extract, the sounds are rendered in quadraphonic playback (reduced to stereo here) transposed and altered by various room resonances (reverbs). That's it. But a warning: the k-bow is no longer supported by its manufacturer Keith McMillen.

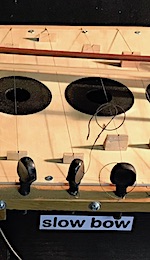

An interactive bow might be framed as technology enhanced music because my use of digital technology does not replace the kinaesthetic relationships or the haptic feedback between musician and instrumental technique, it just extends the creative possibilities. Out of the myriad of bow techniques (détaché, spiccato, ricochet, circular, col lego, etc), extreme and slow bow pressure is the one that classical violinists never go near (I guess they don't do circular bowing either, as they are taught on pain of death to keep a straight bow at all times). This is not to be confused with sub-tone techniques - controlled extreme bow pressure but much faster - producing tones below the normal range of the instrument ( Mari Kimura is a virtuoso at this technique). Having found a box (suitable sound resonator) on the street, I decided on making an automaton that would perform this function and fit well into the new series of bots for the Rosenberg Museum. Unlike a Homo Sapien, a machine will run until mechanical breakdown or someone switches the power off. However with a little human intervention, a wide variety of sonic results are revealed with the Slow Bow. Materials created in the second half of the 20th century never cease to amaze in their musical potential once the original function is bypassed eg. polystyrene vegetable boxes are loud if unsubtle sound resonators. I am forever grateful to Martin Riches for discovering the extended uses of Acrylic Perspex. While busy at work on the Data Driven Violin, he looked for a more reliable material for the wheel bow than the traditional wood used in the hurdy gurdy, and the wafers used in the Violano. He discovered that a Perspex wheel has great gripping power (without the use of Rosin) producing that classic slip-hold-slip-hold phenomenon that gives us the saw tooth wave pattern of the bowed string sound. There are two installed on El Lubricato. And in recent years I've experimented with this idea and come up with a hand held battery powered, flexible wheel. The little 3 Volt motors don't have much in the way of torque but make up for it in speed. I have augmented four to be used with the 32 String Web Automaton. Friction is another way of describing the bow at work and the Help Violin! provides a disturbing use of a violin as dowel holder grinding away on a sonic table top. 'Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of two solid surfaces in contact' it says in the dictionary and who's to argue with that? And unlike a digital loop the Help Violin never quite repeats its call for aid the same way twice. Why reference the golden age of mechanical music as a lunch pad for experimentation? History is rich in options that can be repurposed to take on our current predicaments. The Data Driven Violin delivers, not so much enhanced functionality, but philosophical rationals and processes as to the how and why music should exist. In this case, the real time grubby workings of Wall Street traders and their algorithms can be used to drive a musical instrument that was first witnessed via a church fresco in Milan in 1530. The ugliness of contemporary capitalism consumes the traditional notions of European beauty. Despite automation, the physical limits of the instrument and the imperfection of materials create non repeatable sonic artefacts such as seemingly random harmonics (evident here in the Chromatic Fantasy). AI can already churn out compositions in the style of Bach or Charlie Parker but so far it has proven a less than satisfying agent in the physical expression of music; music remains quite basic in evolutionary terms. Jon Rose 2019 |

|