| |||||||

|

Violins in the Outback Strings Magazine, USA |

|

|

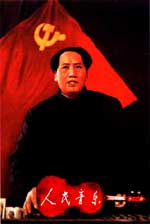

The result was The People's Music (Violin Factory 2), his wild surrealist fantasy featuring string orchestra and conductor along with the various and subtle rhythms of industrial process manufactured by three young Perth composers. Rose served as a second conductor for these "industrials," plus he performed live orchestral sampling and interactive accelerometer-driven string samples (this while conducting with Mao's embalmed left arm, which looked to me suspiciously like a pink plastic dish washing glove). An audience of over 700 had somehow assembled here in the middle of the outback to witness this improbable vision. A Red Guard factory guide was perched above the orchestra on the sheep chute, saluting the agony and ecstasy of the thousands of violin makers in The People's Republic of China with Mao's stern words alternately in Chinese and English. Meanwhile, two videographers projected images onto the sheep shearing shed, a riveting mix of pre-filmed images of Chinese violin factory workers and the live string players. Counterpoint is obviously key to Rose, and this was evident in many small details, such as the portraits of individual string players which ran on rhythmic loops in conversation with the orchestral rhythms. This hour-long work is first and foremost a memorable piece of music and could be approached without the visual and textual components. The string writing alternates between a sort of lively industrial music which manages to impart the factory cliché without being a cliché and inspired moments of meditation reminiscent of Messiaen. Often the chords seemed to be corrupted versions of major triads with extra tones fixed to them, like barnacles to a ship. If elegance is found in refusal, The People's Music is elegant indeed. Formulas and easy tricks were in short supply. For example, Rose incorporated both scored and improvised sections, and while much of it was evidently in loops since the page turns were nearly non-existent, the effect was of a through-composed work. Loops were never placed on a platter for us to admire a la Minimalism but instead disguised, and the result was surprisingly fresh. The next day began with Fence Music--Rose applying a bass bow, plus fingers, hands, and the occasional leg, to amplified fence wires. Two small microphones were embedded in the natural holes of the wooden posts. Several hundred people gathered, not new music fans particularly, but local people nonetheless open to the unfamiliar sounds of familiar objects, open to their landscape suddenly perceived as soundscape. Following the fence music, I fiddled acoustically on an Aboriginal site, Lizard Rock. Even to find it was an adventure. Situated about five miles from the homestead up a four-wheel-drive road with diminishing signs and arrows, then a hike up a rocky hill, the Lizard Rock country revealed an even more rugged beauty then I had yet seen. Several hundred people stood in the direct sun on this enormous red rock to hear me, and I was touched by their committed curiosity. After brunch back at the homestead, we headed out to another remote site for Wire Music. Perth physician and sound artist Alan Lamb had set up several wire installations. For the major one, he stretched two long lengths of heavy duty wire over large boulders and up a hill to collect the sounds produced from the wind. We hiked through the tortuous and aptly named needle grass and across the kinder and gentler rock outcroppings to hear it for ourselves, then descended to a landing where flat rocks lay strewn about like pieces of a gloriously impossible puzzle. We lingered until sunset, 300 strong. I felt like a member of a tribe, our communion enhanced by a stash of champagne on ice in the bed of a pickup truck, its presence seemingly just another natural wonder. see also an article by Deborah Bogle: 'Cutting Edge and Corrugated Iron' (The Australian;03/05/2001) and the new CD 'The People's Music' |

|