Derek Bailey

Guitar Innovator

This text is taken from the programme notes to The Kaos Festival, which took place in Podewil, Berlin, 2-16th November 1992.

The full concert is now available here

In 1985, I invited Eugene Chadbourne to Australia to take part in a small festival of improvised music under the title of The Relative Band. As usual, suitable venues were hard to find in Sydney and we ended up sharing The Performance Space with an experimental theatre group.

After some sensitive discussions we eventually obtained a small playing area in the corner of the main room; the rest of the space was covered waist high in straw. To one side was a mass of barbed wire with an almost inaccessible chair parked in the middle of it, creating an austere presence in the room. We were informed by the theatre group's director that the structure could not be moved. It was non-negotiable.

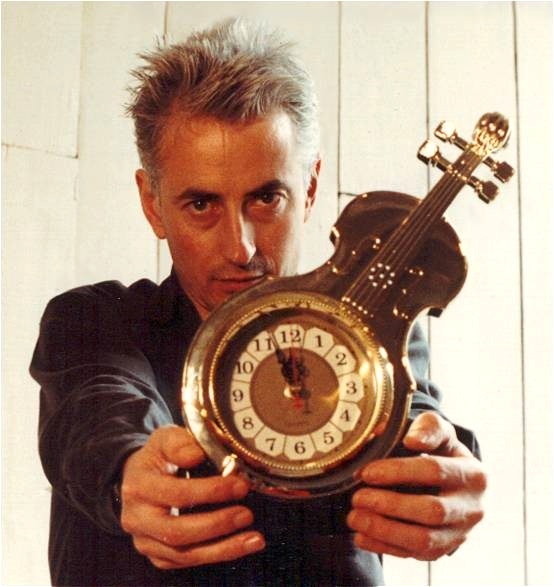

"That's the seat for Derek Bailey", quipped Chadbourne as he strolled in for the gig. It was a joke of course - but that image came back to me when I started to write notes for the Kaos Festival. To a public seeing Bailey perform solo for the first time, he probably represents the classic image of what used to be called the avant-garde: an isolated, Spartan figure, dry, uncompromising. Here's what I do, I play the guitar - take it or leave it.

Perhaps this projected image is part and parcel of the traditional, no-nonsense Northern English character. Those musicians who have had the pleasure of working with him also know that he possesses that wry Northern sense of humour too.

If Jimi Hendrix's major contribution to guitar playing was the sophisticated manipulation of amplified sound through movement in space (i.e. controlled feedback), then Derek Bailey's main influence has probably been his use of the harmonic series as the main structure for pitch events and melodic invention. With his mobile and constant manipulation of pitch through open and stopped harmonics, Bailey introduced and developed the Klangfarbenmelodie concepts of the Second Viennese School into an improvised guitar language. This was a fundamentally different view of the music normally associated with the guitar - it represented a shift from the tyranny of the diatonic chord to a new freedom of pitch relationships based on the natural sonic qualities of the string.

The importance of this cannot be underestimated in the context of improvisation. It would be hard to imagine any of the more interesting guitarists who have emerged in the last two decades doing what they do without having been influenced in some way by Derek Bailey: Fred Frith, Elliott Sharpe, Davey Williams, Bill Frisell, John Russell, Greg Kingston - the list could be endless.

Last year Bailey brought out a new solo CD on his own Incus Record Label. Since his first solo album on Incus dates from 1971, it's a chance to look at his guitar language over a twenty-year period.

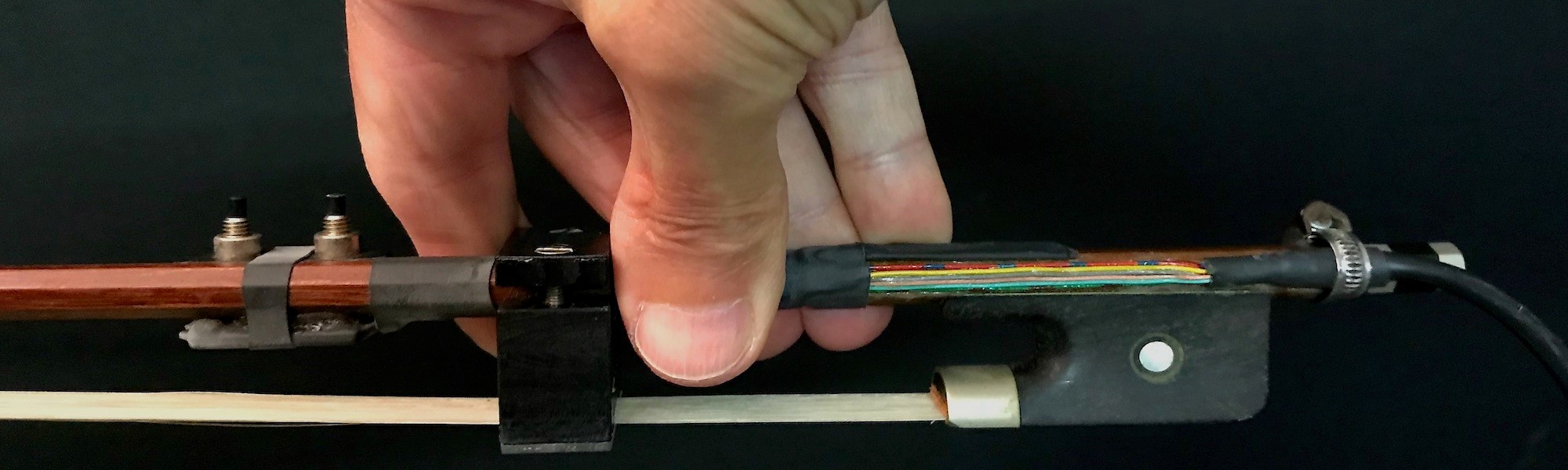

I think it's important to stress that Bailey plays the guitar with a plectrum - he is no Segovia. The plectrum is a weapon (like the violin bow). It's the most fundamental thing in his guitar 'play'. His often brittle style shows a fascination with the initial contact and subsequent transient sounds. Where and how the string is plucked brings into focus the magical world of natural frequencies and nodes - or to put it in an official way: the initial amplitudes of oscillation of the various nodes are influenced by the nature of the excitation. And this focus on the excitation process brings Bailey a highly refined timbral palette. To highlight this ever-varying set of relationships, the guitarist liked to tune his instrument slightly above A 440 to increase the intensity of the sound.

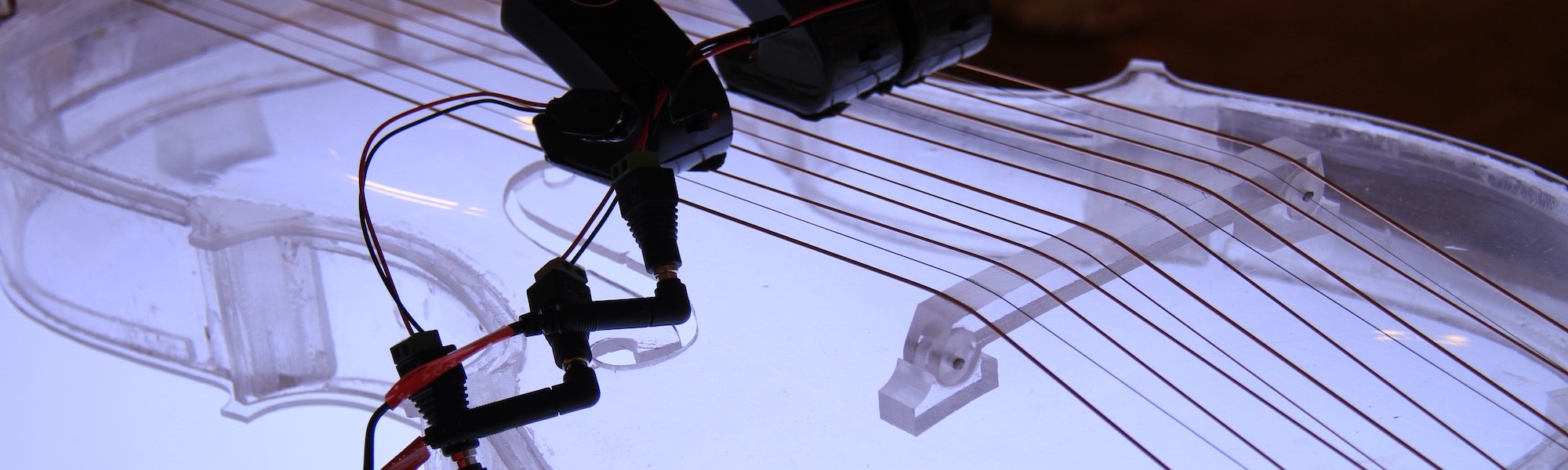

At the centre of the electric guitar is the electro-magnetic pickup. The pickup is 'deaf' to all other nodes on any given string. The pickup position is also critical in the excitation of even or odd numbered frequencies - hence the timbral choice available with two of the standard three electro-magnetic pickups. Exciting the strings in certain positions can cause frequency nodes to cancel each other out or lead to quite chaotic oscillations. There is something even more basic to mention: an electro-magnetic pickup will not work properly if the string is not excited in the first place!

Once the string has been excited, Bailey often spends time interfering with its natural course of sustain and decay. Strings can be dampened, bent behind the bridge, scratched laterally. The use of noise elements underlines a paradox of what is a primarily a melodic style and improvisational procedure.

Another obsession with the guitarist is tuning. Rarely an improvisation goes by without Bailey tinkering with the relative pitch relationships between strings - as well adjusting the standard open tuning for a six-string guitar. (The piece was rarely stopped for this activity). It's not used anymore (sadly), but he used to play a monstrous 10-string guitar with one of the string's pitch controlled by a foot stirrup - the extra length string going through the bridge, out the other side, and down to the stirrup.

In the early 1970s, Bailey used a stereo amplification system and a contact microphone placed near the bridge of his Gibson ES 175 electric guitar. This enabled him to utilize and project in space a larger range of sonic resources than those normally heard from an electric guitar (in particular, transients and some acoustic body sounds). Volume pedals enabled the envelope of attack, sustain and decay to be reversed in real time; a distortion pedal could be used to push clusters of beating harmonics to the edge of feedback - and sometimes over. Added to this was an asymmetric sense of rhythm, texture and pitch transformation, which gave the feeling that the music could go in any direction at any time.

It's interesting to note that the guitar used in this radical treatment was the same one Bailey had used earlier while playing in the ³commercial music business². In recent conversations, he has made it clear that, for him, the development of his guitar playing from session player into free improvisation was a natural one: As a working musician in the late 1950s and early 1960s, an instinct for improvisation and quick changes were a necessity if you wanted to stay employed.

Somebody once said that the history of the electric guitar was the history of amplified sound. It's a point. The basic sound of the electric guitar was not really the most exciting of electronic sounds; many guitarists found it necessary to introduce the 'dirt' with wall-to-wall effects pedals, making the basic amplified sound more expressive (that should draw a few complaints!) How much the affect of these 'effects' had in eventually removing the relationship between guitarist and guitar would probably make a good subject for a book.

For his acoustic guitar playing, Bailey uses an old 1936 Epiphone Triumph, a large guitar with a large sound. His last solo CD is all-acoustic. The music appears simpler; it is clear and spacious - mostly monophonic. There is often a lazy sort of pulse through it. There are still passages of extreme virtuosity - huge jumps change of shape with the left hand, combined with new finger positions and function for each string. Bailey's fascination with playing the same pitch in three or four different ways (reaching the note with harmonics from other strings, or even open strings) remains an important structural signpost in his music.

Structure - now there's a word. To most audiences and critics, it is the lack of this word that keeps freely improvised music on the edges of our culture. By structure, the inference is pre-structure - something reliable, something expected, something that will repeat, something obvious, something not missed. Most writing on music seems to present the notion that expression and form are two different things - opposites, if not contradictions. To me, Derek Bailey's guitar playing presents an entirely structured musical experience. He is not playing any music; he is playing guitar music. The structures and forms derive almost completely out of the business of playing the guitar, and that is also his expression.

© jon rose 1992