stringsville

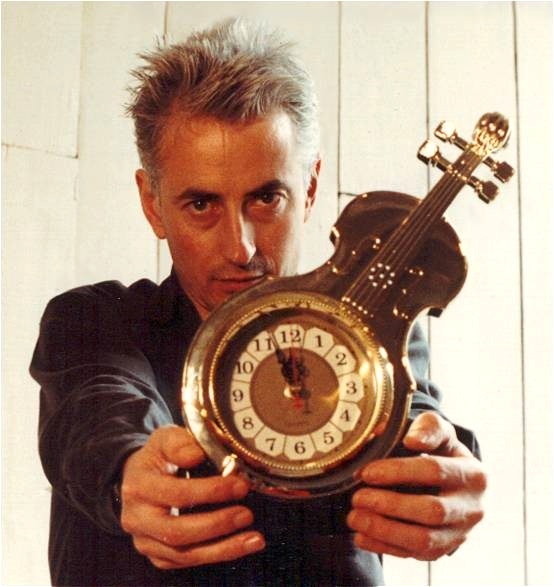

Harry Lookofsky

Throughout the history of western music, fakes, thefts, copies and parodies have always been scattered liberally amongst the perceived genuine article . Amongst them are Kreizler's fake Baroque compositions, Brahms' Hungarian Dances, Mozart's imitation Handel fugues, Bartok's piss take of Shostakovich in his Concerto for Orchestra, and Stockhausen's claim to have invented Buddhist monks in his rip off piece 'Stimmung'. No musicologist or performing rights society has ever held up its hands in horror about the wholesale copying and copyrighting of the aural tradition (Folk music) by western music composers. In fact until recently when ethnomusicology became big business, the official view seemed to be that a composer was doing this primitive stuff a real favour by making it all into proper music. (by curious Reaganomic perversion, the same can be said for some improvisers in the 1980's. In New York and Amsterdam, there was a glut of musician's running around turning improvised music into their compositions.). Until the nightmare of Jazz education arrived, Jazz itself was one area where the idea of a fake was deeply frowned upon. This was probably due to its original inherent quality of being an improvised music dependent on an aural tradition, and developed largely through the business of live playing. Well, this was true up until the 70's at least; since then it's become just another academic study with its consequent demise as a living artform.

Here's an odd piece of jazz history that doesn't fit at all into the defined character, practices or the modern decline of that music. It's about an innovative jazz player who wasn't a jazz player. He invented an improvisationary language that never existed (and his name was not Rosenberg either). He was an unsung genius of 20th century music and his name was Harry Lookofsky.

In 1989 I had the opportunity in Berlin to organise a Festival around the violin - The Relative Violin Festival. A sort of look at the instrument from a contemporary music viewpoint. One of the violinists we invited was called Harry, I spent quite some time on the phone trying to get him to come. In the event he never made it to Berlin but the conversations we had I edited down and wrote out for the Festival catalogue...

In 1958 a record was made for the Atlantic Label in New York, it was called Stringsville and it featured a relatively unknown violinist named Harry Lookofsky. Play this record to any violinist or knowledgeable jazz fan and a warm smile will come over their faces, followed by reliable exclamations like 'incredible chops' or 'unbelievable playing'. They will probably have to agree that this is THE definitive Jazz violin album. It makes Stuff Smith and Eddie South sound quite unimaginative and crude and Grappelli sound even more like sirup (the fusion players of the 70's don't rate a mention I'm afraid). Lookofsky's playing has the sophistication and power of a classic Bebop horn player...a Charlie Parker or a Sonny Rollins. Yet this album is almost totally ignored by jazz history books. Why? As we will discover further, it was not a REAL jazz record and it was not played by a REAL jazzer. But it was arguably played by one of the all time greats of the violin.

Harry Lookofsky was born in Paducah, Kentucky in The United States on October 1st, 1913. He started to play the violin at the age of 8 years (quite late by classical virtuoso standards) and received his training in St. Louis, Missouri. In his early teens he played The Vaudeville Circuit in the South with a small jazz orchestra.

'I had as my model in that time, the violinist Joe Venuti. I used to listen to him all the time'.

He stayed in St. Louis until 1938, having in 1933 also joined The St. Louis Symphony Orchestra.

'Then I came to New York and I joined Toscanini and the NBC Symphony - that was something!'

Was Stringsville the first 'jazz' album he made?

'No, the first record I made was for the Epic Label of Columbia -the name? I'm having trouble remembering. I'll have to write you a letter! And there was this saxophone player, Leo Wright - used to play with Dizzy Gilespie; I made a record with him, yes, I played on half of it in fact. I'll send you that.'

This record actually came out on The Atlantic label after Stringsville, it was called 'Blues Shout'. There are two solos from Lookofsky that are quite extraordinary. In terms of jazz styles and history, these float in a Steve Lacy sort of way over the rhythm section. Incorporating elements from Joe Venuti as a jump off point, the violin lines hint at the whole development of jazz up to and including Bebop. The solos have the classic saxophone and trumpet phrasings of small repeated rhythmic units, slurs and grace notes. On 'Angel Eyes' the playing is spacial and hangs there in a vibratoless line. Indian Summer on the other hand is full of condensed phrases that seem to come out of nowhere...accelerating through the barlines. Towards the end of this solo comes a wonderful and continuous piece of effortless bop phrasing...a superstructure of referential tonality (bound to earth unfortunately by the rather pedestrian changes.)

Harry Lookofsky was the first (and perhaps only) violinist to sit down and spend a lot of time figuring out how to play Bebop on the violin, an instrument which is a nightmare of technical demands. But he cracked it. In some ways he rediscovered 'Early Music' techniques which have become now so fashionable in the playing of Baroque (and later) music... eg. lack of vibrato, or using vibrato as an affect instead of continuously as in the standard playing of the classical repertoire. eg. using very light, fast bowing similar to the 'Messa di Voce' bow strokes of the Baroque period and before. (These two techniques are of course an integral part of the world music string tradition in many countries but lost in the western music education system in this and the last centuries.) Lookofsky combines his bowing with a faultless intonation from the left hand in all positions and at amazing speeds...apart from having talent (lots) a violinist only gets these kind of chops through years and years of practice.

The music never sounds stiff...the usual and often correct complaint about classically trained violinists (check out the hideous duo records of Menuhin and Grappelli). Often the bowing is reversed, so the normally stronger 'Downbow' happens on the second and fourth beats of the bar (generally the weakest beats in classical music but the 'swing' beats in Bebop). Some of the rhythmical phrases on Stringsville are extraordinary...crossing bars, metric subdivisions, slowing and speeding of tempo, colliding rhythmic ideas together in mid phrase, etc.

'Why don't I write something down for you and send it over, I'll put the bowing marks through it...then you'll see the kind of thing I did on the album. Oh! I just remembered the name of that first album; it was called 'Miracle with Strings'. It was different to Stringsville, it was the beginning. I made it at the time that Charlie Parker was popular, in the early 50's. Oscar Pettiford played bass and Charlie Swift played drums. I've been trying to find a copy of it, I don't have one. There must be one somewhere, I've have to call you back ...

In those days, there were no multitrack tape recorders, only single track. So Epic records had me play each string part (3 violins, 2 viola parts) on a separate tape while I listened to the rhythm track, which was itself on a separate tape: Then, lining up 6 single track Ampex machines, each with a part and all connected to a common 'starter' box, they did their best to put it all together! After many starts and stops together with splicing, they wound up with the album. It was different when I came to do Stringsville'.

The opening track on Stringsville is an arrangement of the Monk classic 'Round Midnite'. The theme is 'placed' rather than 'played'. On the repeat, the violin takes off on an unexpected, breathtaking flight at top speed, the complete contrast. (See the first music example of Harry's written out solo with bowing marks). This kind of extreme juxtaposition is typical of much of the playing on the album. In the middle 8, another element is introduced...a multitracked string section...close parallel harmonic movement, sometimes an internal moving line. Again this is very characteristic of the album; it's as if the whole Duke Ellington Band had turned up on the session playing violins.

'Moose The Mooche' features a tenor saxophone solo. And that's the only way to describe it, played I assume on... a tenor violin?

The next tune is 'I Let A Song Go Out Of My Heart' and has some beautifully played 'flat' notes on the E string, a great full horn glissando (a la Ellington again), and a solo line that balances tonal ambiguity on a knife edge (predating I suspect The George Russel Lydian Chromatic Concept, which has been regurgitated by every Jazz student world wide for the last 20 odd years).

On 'Little Willie Leaps', a tune written by (pre-face lift) Miles Davis, the head is played in octaves (tenor and normal violin). Like many Bop tunes, this falls very awkwardly for the fingers on a violin. Lookofsky takes it at a blistering speed. The first solo break has some short motive figures that cross the pulse in a kind of 'no-time' land. The third break starts with nearly three octaves of fourths piled up on top of each other...quite a radical way to start a Bop phrase, it's more like the modal approach that was to come in the 1960's. For most of the time on this tune, it is an interchange between Bob Brookmeyer (Trombone) and Lookofsky. The other players on Stringsville are Hank Jones (piano), a pre-Coltrane Elvin Jones (drums), and Paul Chambers alternating with Milt Hinton (bass). They are all in excellent form.

Side 2 continues with one of the hottest versions of 'Move' imaginable, the violin powering through a blur of 16th notes.

'Champagne Blues' and 'Give Me The Simple Life' are both medium tempo numbers and the violin section work mimics the clichés of the 1930's in their arrangements. Then there is a bizarre 'tag' on the end of 'Life' with a wild echo chamber effect on the violin part, like a sound track to a horror movie. The last track 'Dancing On The Grave' uses straight out Blues phrases against a background string section doing an 'Ol train 'a comin' routine as a soundscape...high kitsch this one! It avoids painting a complete picture of deep south romance by injections of straight ahead material, kicked along gently by Elvin Jones.

On Strinsville then, Harry Lookofsky plays violin, viola and tenor violin - all with phenomenal technique, flare and feeling. But what exactly is a tenor violin?

'I read about this kind of violin in a New York magazine and I went to Wurlitzer and asked the manager if he could get that instrument for me...and he did. They were in business with this firm, it was a German Firm in Mittenwald. So they sent away and got it for me. It was like a viola but with much deeper sides and the strings were tuned an octave lower than a violin. It had strings on it that didn't sound so well, so I went to a string maker and he made up a special set for me...they were very thick! The instrument suited my purposes perfectly...I made it sound like a tenor saxophone. I don't have it anymore, somebody stole that instrument from me'.

Lookofsky has no trouble going from one instrument to another, the intonation remains unbelievably true.

'Oh yes, I use my ears! And I bend my fingers a little bit more than I should. It was also an unusually large viola, it was really too large for me to play'.

There is evidently more than one Lookofsky on Stringsville but had multi track recording then, aleady arrived by 1958?

'I did this on the first multitrack recording machine that was commercially available, it was an Ampex 8 Track. We put all the rhythm section down on one track, that left 7 tracks. So then I would record using 6 tracks and then transfer them over to the seventh. Then I would record on 5 and transfer them over to the sixth...and so on. Some of it was very deceptive stuff! Making each part start in a slightly different place, for example, is not so easy...but when you hear it back, it sounds like the whole orchestra is in sync, playing as one'.

Who made the arrangements?

'Well Hank Jones wrote some very nice things and also Bobby Brookmeyer. Those two did most of the writing. But a lot of things I worked on myself. Bobby and Hank weren't string players. There was plenty of room to do what I wanted to do. The solo passages I worked on mainly with Hank, we tried things out. He might suggest a phrase and I would see if it could work on the violin or not'.

So this is definitely against the rules and hype of jazz! Most of this record was played from written music, all of Harry's 'improvisations' certainly were. It sounds like he's really blowin' (man) on this record but he was reading the whole thing off a music stand from beginning to end! So is it authentic jazz? Living as we do now in a world of sampling, jazz 'educators', play along CD's, video clips, obscene jazz festivals and virtual reality home remixing of your favourite idiot rock star...Stringsville seems a remarkable and exciting document, musically, technically and conceptually.

The idea of playing a written out solo and pretending that it was improvised would not have been a very 'hip' thing in the 1950's. So no mention was ever made about this on the record sleeves. Indeed elsewhere, Leonard Feather keeps the jazz myth in tact by writing a total fabrication 'The ex-symphony man who stopped in mid career to become a jazz violinist'. Harry was all the time playing with Toscanini and the NBC, he never stopped to become a 'jazz man'. Leonard Feather, however, has a vested interest in making sure jazz history and mythology runs how it is supposed to run.

Anyone listening to this record can hear that, no matter what kind of process was involved in making it, it is clear Harry L. has total empathy with, respect for and love of the bebop idiom. Nevertheless, he was an outsider who arrived in jazz history, made an extraordinary contribution, then disappeared hardly noticed. Were there any other motives for making this record? The original sleeve notes quote Harry as saying...

'To me it seemed to be a problem of communication. As a violinist, I had to find away to talk to jazz musicians - and in their language. I knew that if I could, I could make them accept the violin in a jazz group, as another 'horn', not just part of the background'.

How long did it take to record?

'Well, we put down the rhythm section material in two sessions. It was a very small studio, I remember everyone had to walk sideways to get around the piano and drums. Then I think I came just twice to put all the strings down. I knew what I was going to do. There was only one second 'take', I had to re-record the start of one of the overdubs. You know the equipment was very primitive, each track on the Ampex leaked over into the next one. Apart from that I don't remember having to do anything over again, we sailed right through it'.

So the Stringsville album was made. Having created this achievement, hadn't Harry also wanted to fulfill the American dream and become famous, if not rich as well?!

'No, it never interested me all that stuff. First of all I was playing with Toscanini throughout this whole period and I really loved to do that... I didn't want to stop. And I wanted to keep studying, I kept practising all along. I got up this morning and practised. I'm really just a violinist. All that travelling, jazz life...well, I wasn't really into it, though I knew the scene intimately. I used to go down to Birdland with Quincy Jones to check out the players. When Toscanini retired, I also quit the NBC and went over to the ABC as concert master of their orchestra. I was with them a long time and then there were economic cut backs, so they got rid of all the strings. In the last 10 years I've been getting by doing Television jingles - that kind of thing...and playing golf, I like that a lot'.

The archaeology of jazz is the record album; the myths and the everyday working realities of this music are stored in that medium. In some ways, Harry Lookofsky made a set of beautifully crafted fakes....it certainly (by intent) wasn't anything to do with jazz transcriptions. He created from and played with the full range of aesthetics (musical and otherwise) that go to make up the jazz culture; he made a jazz album about jazz albums. Stringsville was a post modern project way before its time.

'You know after the last time we spoke I was looking through some old stuff and I came across a tune that Clifford Brown wrote for me. I don't believe anybody else has it because he wrote it just for me, would you like to see it? I can send a copy over to you. I knew Clifford Brown and felt crushed by the news of his death (26.6.1956 in Chicago). A sweeter person never lived and of course we all know his playing greatness. When I asked him to write something for me, he graciously said he would and invited me over to his hotel room on Broadway and 53 Street. I brought some manuscript paper from the ABC where I was working as a staff musician. (At that time also on the staff, amongst others, were Billy Butterfield, Bobby Hackett, Peanuts Hucko, and Ruggerio Ricci!) When I entered Clifford's room, he quickly put on his underpants and, while in that state of dress, sitting on the bed, he dashed off this composition, with a solo on the second page. (see the second manuscript illustration).

In more recent times Harry Lookofsky has become interested in the idea of 'jazz transcription' on the violin. The last project was actually about gospel music. Quincy Jones asked him if it was possible to imitate the sound of a gospel singer on violin, for a film sound track. Harry thought he would give it a go. Aretha Franklin singing Amazing Grace was selected. Lookofsky made a version dubbing 29 times the exact contours and inflections of the original voice improvisation. The result is a beautiful warm, lagging and singing line. In the event of course, the director dumped this quite original idea for a (true to market principles) piece of mundane funk.

'I'm sorry I can't make it to your Relative Violin Festival, but what could I do? I don't think I could really add anything to what I did back then. It was a statement. Also Berlin in January...I don't think I'm up to it. I want to go to Florida and play golf'.

Taken from the ReR Recommended Source Book 0402 (1995). © Jon Rose 1989.

Recordings of 'Stringsville' are available on request from Harry's widow Sherry Lookofsky.

Email: sherrylookofsky@comcast.net