Press Quotes 2014-2019

Jon Rose

what others say

This page consists of descriptive reviews from The Wire, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Guardian, Cadence magazine, The Voice, Realtime Magazine, The Australian, New York City Jazz Record, Cyclic Defrost, Time Out New York, All About Jazz, Limelight Magazine, and many more.

'The composition and Rose's performance were phenomenal. From the staccato beginning to bow air swipes and syncopated percussion, the whimsical aspects had patrons stifling laughs, and orchestra members smiling. Rose employed just about every violin technique imaginable and some you've probably never thought of; his serene face mismatching his output. A masterfully constructed piece with dreamlike harmonics, double bass sounding more like wind, and a percussive finale was received with elation.'

GLAMAdelaide

'Sparks fly when the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra rubs up against a clutch of avant grade musicians. Elastic Band coaxes sounds out of the Adelaide Symphony that may not have been heard before, not least the string section slashing the air with their bows while soloist Rose, standing like a matador (who is the bull?), plays notes that sound like a stressed-out R2D2...a huge success.'

The Guardian

'Bold experiment in new music a winner. At last the Adelaide Festival has come up with a bold and creatively memorable musical program. David Sefton, in his second year as artistic director, has given the festival a long overdue dose of innovation at music's pointier end. What it particularly showed was how improvisation is the real lifeblood of new music. Paving the way were two festival commissions performed by the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra. Elastic Band, by Elena Kats-Chernin and violinist Jon Rose, was unique as far as collaborations go, superimposing Rose's frenzied improvisations over a written structure that both he and Kats-Chernin had notated for the orchestra. Cheeky in its bizarre confluence of styles, it was engrossing to witness.'

The Australian

'This is a remarkable trio. All three operate in their own space but unite to make a true group music. This fully improvised set dwells in minute details taking the listener deep into their sound spectrum. The group interaction is acute and all three seem to are on the same wavelength. Rose plays violin and tenor violin. Oddly, this sounds like an almost purely acoustic music, odd considering Barrett's electronic presence. But the sounds he elicits are such complements to Rose and Kneer's otherworldly string playing (lots of spectral harmonics, unorthodox bowing methods and percussive pops from the body of their instrument), that acoustic vs. electronic issues never enter into it.'

Cadence Magazine

'Rose pulled his strings in every imaginable direction and as frequently whipped his bow in the air or bounced it off strings as he carved expressive passages from his instrument.'

New York City Jazz Record

'The first day opened with the biggest blockbuster of the festival - Colophony trio in the cast of Jon Rose (violin), Meinrad Kneer (bass) and Richard Barrett (keyboards and electronics). Rose returned to the stage after a protracted illness in phenomenal form, a constellation like this for him is literally living water. Unfortunately this trio set the bar too high, thus more stars of the evening remained somewhat in the shade of a supernova.'

The Voice

'The train and its journey is a metaphor for white Australia's long history of struggle to cross borders, join isolated towns and pretend Australians are 'one people' with a shared goal - to produce, to provide, to survive and to conquer. Jon Rose's Ghan Tracks includes footage taken by Rose and Mark Patterson of the huffing, muscle-bound contemporary Pichi Richi Railway (the only part of the Afghan Express still operating) and the Old Ghan rusting in retirement, against archival footage of her heyday when she was a 'slow silver ribbon' with polished interior finishes and plush dining-cars.

Rose - an artist who has staged his work on, along or across boundaries such as fences dissecting the Strzelecki Desert, the USA-Mexico border and the Separation Fence in the Israeli Occupied Territories-excavates the romance, the struggles and the ironies of this mythology in a sound/performance/installation work involving seven musicians, a lighting artist, a sound technician and himself - a white-haired, hyper-charged piston engine driving the work through transitions by waving pieces of numbered, coloured paper at his orchestra.

Along with clarinet, tympanum, sousaphone, piccolo and corrugated iron, the ensemble also includes a rain machine harnessed by pedal-power and a canvas draped like pastry over a turning pin, which is wound like an oversized meat-mincer to create the sound of wind. Several times, Jennifer Torrence shovels gravel into a cement mixer, walks behind, turns the mixer, and then tips it out into the pit again. The steady dryness of this action, the brittle grind of the sound and the measure of Torrence's footsteps is enthralling. This above all else serves as a synecdoche of the desert, of the hopes that people kept pinning on 'good prospects' and full crops (which all failed) north of the Goyder line, representing the gap between expansionist dreams and the moisture desperately longed for but which never returned. This dry truth is also echoed in the gap in tuning between the equal-and just-tempered vibraphones, to my eye matched also by the footage of coiffed women with slender fingers pointing to a dream outside the train window that we never get to see. Not quite visible or audible.

What I appreciate most is the delicacy in the use of film, a rhythmic/visual intervention appearing and disappearing in and out of score as do the instruments themselves. There are archival stills of Aboriginal children posed in stiff dresses beside sombre, starched white women, or taken on camel-rides by the Afghans. Another camel carries a pianola strapped to its back; where we might expect romantic keyboard tones, Rose overdubs the camel's screaming song. A low POV shot, taken from the track itself as the Ghan passes over, is an apt symbol of obsession overrunning reason. Footage of the last run of the Old Ghan, pulling up its own tracks as it passes, like a spider eating its own young, is a sad homage to the folly of its past. As if we too could hoist up our limbs and say goodbye to dreams laid in sand.

Readings from old newspapers performed by Patrick Dickson and Lucy Bell capture the dashed hopes of the early settlers. The only strange element here is the full downlight on them, suggesting human superiority in the telling of this tale while the stage is otherwise discretely lit, spotting the curve of the sousaphone, the bell of the tympanum, the gleaming edge of the vibes.

Rose has been careful to document what the train meant to desert elders. A shot of the engine appearing like a caterpillar around the corner of a fat gravelly mountain is accompanied by a voiceover of Peter Paltharre Wallis telling the story of the black 'devil dog' eating up the ground. There follows a beautiful tract of Arrernte language, unmitigated and untranslated, holding its own.

Copious program notes unwind of Rose's critical politics. Yet Ghan Tracks is a curiously conservative listening experience, its structure built on regular metre (appropriate, perhaps to the rhythmic forces of a train, but certainly not to the Old Ghan's breakdowns!), albeit full of surprises and textures of which I value the reminder to take heed. The Ghan is less a radical take on the world around us than a reminder of the constancies of the battle between us and the environment, but yes, a cautionary tale (as Rose would have it) on how we may lay tracks into our future.'

Realtime Magazine

'In short, the concert was incredible. The composition's arrangement, coupled with the projected multi media pictorial and audio narrative, enabled audience members to totally immerse themselves in multiple tiers that mapped The Ghan histories. The piece's duration and cyclic crescendo conveyed the expansive Pitjantjatjara country north of Adelaide. The timely immersion of an electric cement mixer (visual) and stone/concrete pit (audio) into the composition was inspired. Good research uncovered remarkable histories, including an audio track that documented a Pitjantjatjara man's first responses to seeing The Ghan. At first, he and his friends/ family thought the train was a giant caterpillar. Additional pictorial footage from the outback featured Afghan camel drivers and Lutheran missionaries. The inclusion of archival material helped map an understanding of how The Ghan impacted upon the cultural life of this remote region.'

Museum of Fathers

'When a nation reflects on lives lost in far-flung wars, the uncomfortable truth may be that closer to home that there are some horrors that remain forgotten and shrouded in silence. But not until we face them can we find peace. Adelaide's new music innovators Soundstream Collective made that abundantly apparent in "Silence Augmenteth Grief" a concert themed around "the tragedy of war and the suppression and silence that follow", to quote the group's artistic director, Gabriella Smart...Jon Rose's Picnic at Broken Hill, receiving its world premiere, consisted of a musical transcription for detuned upright piano of suicide notes left by two protesting Muslim camel-drivers after they opened fire on a picnic train near Broken Hill in 1915. Two "voices" on the colonial d-tuned piano meandered against one another, one high and the other low, without ever quite coinciding in time. Adding to this piece's simple but powerful impact were images projected on a sidewall in Adelaide's Samstag Museum of photos taken after the shooting, showing a Turkish flag and bullet holes in the side of the train.'

The Australian

'The Rosenberg Museum... is musically perverse, historically bent, and politically incorrect. What weighs more, "The Rite of Spring" or Kate Bush's "Running up that Hill"?'

Art in Berlin

'In "Not Quite Cricket", Jon Rose reaches into the well-known story of the first Australian cricket team to play at Lords and draws out a tragedy dressed up as music hall comedy, in what he calls a "historical intervention".

Rose is an Australian-based polymath creator: a musician, inventor, composer, improviser, educator and entertainer. Radio production is just one strand of his prolific body of work. Over decades he has forged an innovative style, a distinctive radio form. His work has always been a fusion of genres, a hybrid of fact and invention with composed and improvised music carrying its own narrative. With music as a given, Rose has politics, history, and often sport in the mix. As an advocate of Indigenous language and culture he's worked with a number of Aboriginal elders, teachers and performers in his radio pieces, and projects over some years reflect this commitment. "Not Quite Cricket", like other recent works, has the loss and partial restitution of Aboriginal language at its heart. Cricket was the first white team game in Australia and squatters [land owners] soon had Aboriginal workers playing this quintessentially English game. It was an Aboriginal team with members recruited from the Western Plains of Victoria which, in 1868, toured the United Kingdom. Rose retells a tale that has often been represented as a triumph for Aboriginal Australians and his take isn't so positive. He challenges the assumption that this was a glorious moment for Indigenous sportsmen and reveals what's latent in the unquestioning versions of the tour; he views it as a titillating racial freak show, a historical record of racism, exploitation and brutality.Jon Rose's striking music and characters conjure a palpable world. It's true radio virtuosity, playing with the medium and creating a radical, satiric review of history, using music and seductive humour to deliver a tough, sometimes shocking, message.'

Radio Doc Review

'Brilliant Australian violinist and fabulist Jon Rose.'

Time Out New York

'It is a music of the landscape; the phenomenal sustain created by long stretches of tensioned wire seeming to amplify the magnitude of the land. Metaphors abound, and when the wire is barbed, they assume a darker hue. Initially, Rose stopped playing between the film's short segments, but when he began to play across those "rests", a stronger, more coherent dialogue between live and recorded music emerged, his violin commentary adding layers of contrast and complexity. One could debate the ultimate relevance of virtuosity to free improvisation. Certainly, Rose's phenomenal command of his instrument increases the sonic options at his disposal, especially in terms of colour, texture and density. These were more fully explored in the first-half duets with guitarist Julia Reidy.If he has a bottomless pit of ideas, then Reidy is fast digging one. With both instruments amplified, innocuous sounds could become a frenzy at the push of a button.

Regardless of dynamic level or intensity, the interaction between Rose and Reidy was intricate, open and sufficiently propulsive to avoid stasis in one sonic zone. Just as the mood could flick between humour and drama, all aesthetic options were on the table, from exquisite beauty to belligerent feedback. Then there was the intrinsic theatre of the extended techniques that both employed, resulting in a myriad of exhilarating sounds.'

Sydney Morning Herald

'The result is unusual to say the least, and often stunning, not the solemn or reverent sounds you expect in churches, but rather the nervous and agitated sounds that correspond with nature on a windy day, when trees and grasses and plants wave back and forth, pushed in the same direction, full of intensity and relentless dynamics yet without moving as such, still firmly rooted somehow in the natural sound of each instrument. Or is it not? Not entirely, because not only are the organ stops used to create microtones, the strings are also tuned differently to allow for a better and more surprising interaction and dialogue. Jon Rose compares the collaboration of organ and strings to the most basic animal digestive system : wind, guts and pipes. This sounds irreverent, and the music itself is not as digestive as described here.

Quite to the contrary, the effects of the quarter and eighth tones result in quite surprising music, totally unfamiliar and new, yet at the same time strangely welcoming too. You do not always grasp what is going on - at least I don't - yet the combination of sounds is strong, and leads the listener to dark atmospheres, fresh surprises, light and playful interactions. Like with all good music, you can only surrender to what is being presented, and enjoy the journey, even if it leads you to uncharted territories.'

The Free Jazz Collective

'Violinist Jon Rose is a regular guest at People's Republic, in fact he's described as a 'mentor' of the place, and tonight he's playing a duet with improvising guitarist Julia Reidy, formerly of Gumbo, who's just returned home from Berlin. She has an array of implements she uses on her guitar, including a drum stick, steel wool, various metal objects, and what looks like a computer mouse but turns out to be a bottle of blue fluid. Both she and Rose play electrified instruments, and sometimes it's difficult to tell which is which, with Rose alternating between bowing, plucking and hitting the wood. Both musicians provide a dazzling array of amplified sounds, few of them conventionally associated with either instrument, and an intense level of interaction.'

Cyclic Defrost

'But, given the central role of the organ, the strength of this album is the way that the three instruments come together in a coherent three-way collaboration that is not noticeably dominated by any of them. The tour was publicised as 'exploring new territories in micro-tonal tunings using pipe-organs and re-tuned string instruments.' Sure enough, the tunings of the cello and violins are different to normal but they work well with one another and with the organs, the three always being complementary if not conventionally harmonious. The proof of this pudding is in the listening - and it works well, handsomely repaying prolonged listening and revealing new facets over time. Yes, Tuning Out is definitely a positive addition to Emanem's already excellent canon of albums featuring improvising strings.'

All About Jazz

'Jump Up Review: Let the games begin. While composed music can be playful, improvised music almost inevitably is, with more overt 'game' elements sometimes emphasised or even formalised. From an audience's standpoint, improvisation unfolds in real time as both a process and a finished product simultaneously. Jump Up was a one-off collaboration between eight improvisers who had never played collectively before. Rather than leaving them entirely to their own devices, violinist Jon Rose curated the concert in ways that guaranteed a diversity of musician combinations and dynamics. The first half consisted of a single 40-minute improvisation in which, with a digital clock as a reference, Rose provided the players with a timeline of who would play with whom, when, in combinations from octet to solo, and with occasional dynamic indications. At the kick-off, anarchic humour set the tone when pianist Mike Nock's gentle, almost pastoral, introduction was suddenly trampled by a mad cacophony...'

Sydney Morning Herald

'Experimental violinist Jon Rose joins the ensemble for The Threepenny Violin. Bright introduces the piece: 'I like fences and shapes but Jon just wants to be free.' This tension plays out in a furious improvisation bound together by samples of playwright Bertolt Brecht giving evidence in 1947-48 before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Rose propels the music forward with a flourish of crunching pizzicato, his bow bouncing radio static on the strings. 'Bertolt Brecht' repeats over and over again. The music is a devilish hoedown, flecked with slapstick comedy and frenzied energy, the voice of the interrogator needling: 'Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist party of any country?' Chaos splinters into moments of lyricism with quiet impressionistic piano from Bright. Rose declaims loudly in German. A militant snare drum heightens the sense of anxiety and the bass clarinet lends a cabaret festivity. Rose's bow shredding reaches a fiery climax: the band cuts off, leaving the violinist alone to play a blistering cadenza. Light taps from the drum-kit gradually bring the other instruments back in for a lighter, swinging conclusion.'

Realtime Magazine

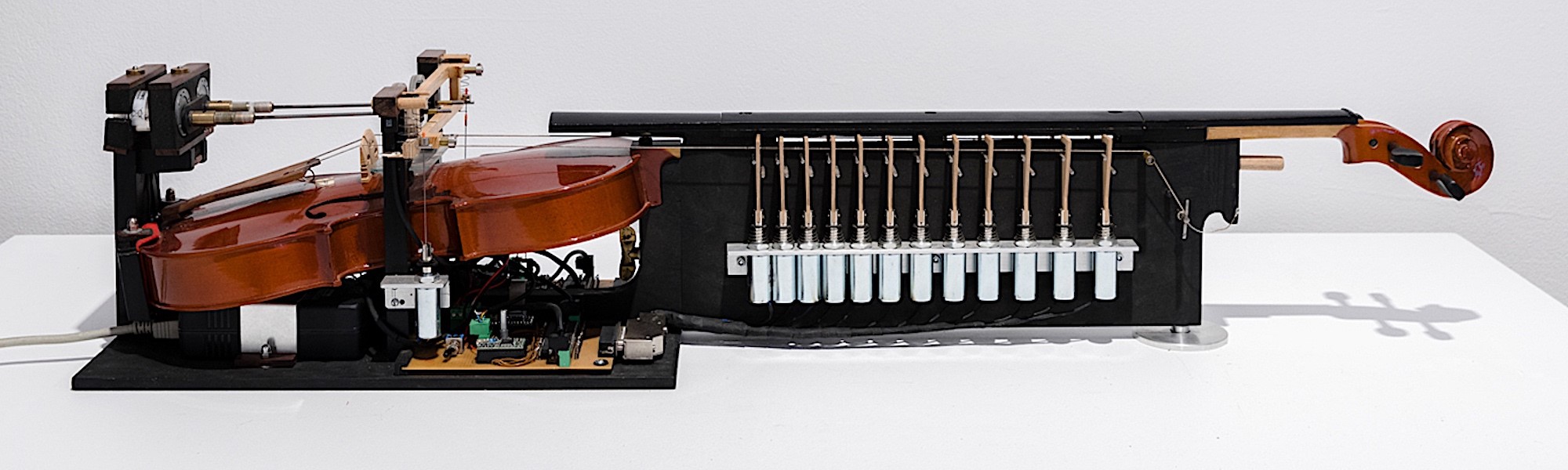

'Experimental violinist Jon Rose creates a terrifying performance that brings his museum of instruments to life. A gritty buzzing came from the centre of the room, where a violin, expanded with machinery, produced a discordant, random-sounding music. The Data Violin - a robotic instrument that turns information from Wall Street into sound - was the centre-piece of experimental violinist Jon Rose's Music in a Time of Dysfunction - Part 1.

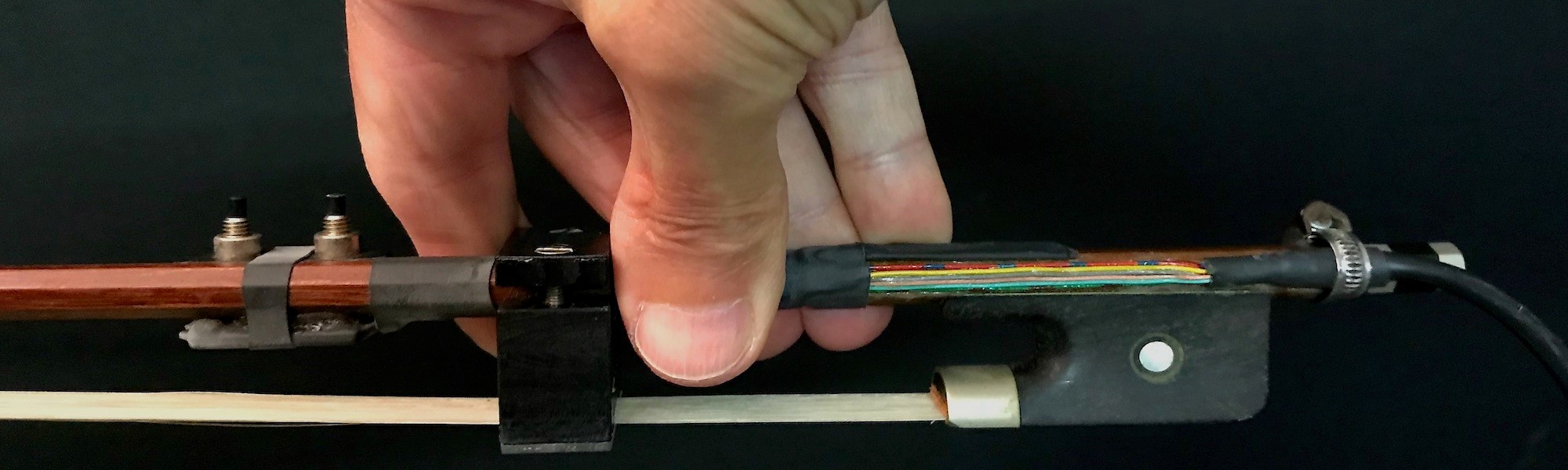

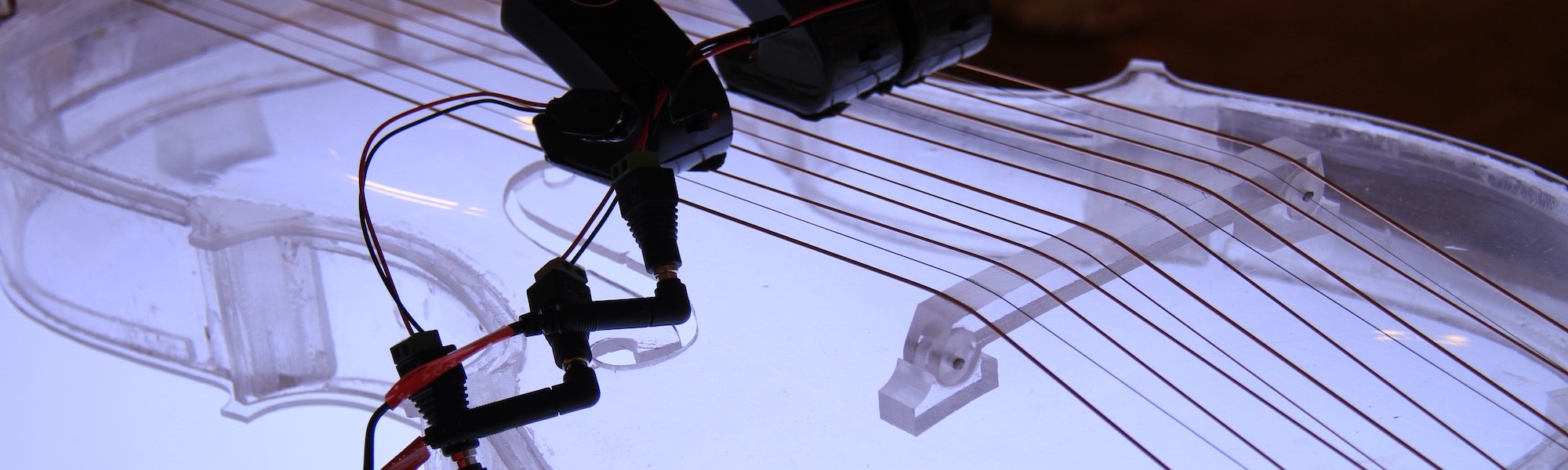

The Data Violin intermittently whirred to life and fell silent. Sometimes it sustained tones from one or both of its strings and at other times frantic activity from the mechanical hooks that lined each side of the instrument threw out virtuosic flurries of distortion-heavy notes, the tone not unlike that of an overdriven electric guitar. Beneath the more violent sounds of the Data Violin, a softer tinkling of piano came from behind the audience - a player-piano performing a transcription of the sounds heard on a walk around the busy gaming room of the Sahara Casino in Las Vegas. The instruments are part of The Rosenburg Museum - Rose's personal collection of violins and violinalia, which includes everything from bizarre instruments and images of violins, to home-made creations, toy violins and violin-shaped scotch bottles. Rose took the stage to make an adjustment at the Data Violin and queue Julia Reidy on electric guitar - a staccato repeated note - before taking his place at a strung, electric, wooden two-by-four that served as bass and percussion. Rose and the other instrumentalists - an expanded 10-piece Ensemble Offspring - surrounded the audience, the performance taking place across space as well as time. Plunged into darkness, machines whirred to life - automaton musicians augmenting the live ensemble - clicking and tapping coming from all directions as standing lamps flashed on and off, snaring the audience's attention and splintering it across the space. No matter where in the room you sat, there was no way to take it all in. A string quartet played from a platform, shooting harmonics and slides, while percussionist Claire Edwardes bowed an instrument consisting of a large metal frame strung with different kinds of fence wire - a product of Rose's investigation of the sonic qualities of fences across Australia. Edwardes produced shining harmonics, brittle, scouring barbed-wire sounds and guttural low notes from the amplified instrument, crisp pops and echoing thunder as she bounced the bow on the wires. Pianist Zubin Kanga drew ethereal sounds from a decrepit junkyard organ. The click of the standing lamps became part of the bewildering sonic and visual environment, rapidly spotlighting musical gestures - a sensory overload of flashing sound and activity that fuelled a swiftly rising anxiety. It became impossible to parse which sounds where human and which mechanical or electronic, the museum transformed into a kind of mad, haunted-house. Reidy put down her electric guitar to mount a pedal-bike-turned-instrument that produced a textured rattling until she hit a button that filled out the sound with amplification and roiling pitches, her legs pumping the pedals. Electronic distortion and static spurted out of speakers, angry buzzes as if the flashing lamps were shorting out, the machines catching fire. Rose warped sickening lawn-mower pitches by adjusting the strings of his two-by-four. Tonal figures from the string quartet permeated the onslaught, the sound-world disintegrating. The quartet's music became lush, almost romantic, against cooling-engine ticks, like a record player that is somehow still playing, weakly, in a bombed out city.

Rose packed an enormous amount of sensation into a performance that clocked in at a little over 30 minutes. This was not a comfortable experience, but it was intensely vivid and engaging, with a frightening, economic lighting design consisting almost entirely of standing lamps. Music in a Time of Dysfunction - Part 1 was a masterful curation of chaos, highlighting the alarming experience - which is part of, but veiled in everyday life - of being held in thrall to complex systems we cannot fully grasp.'

Limelight Magazine

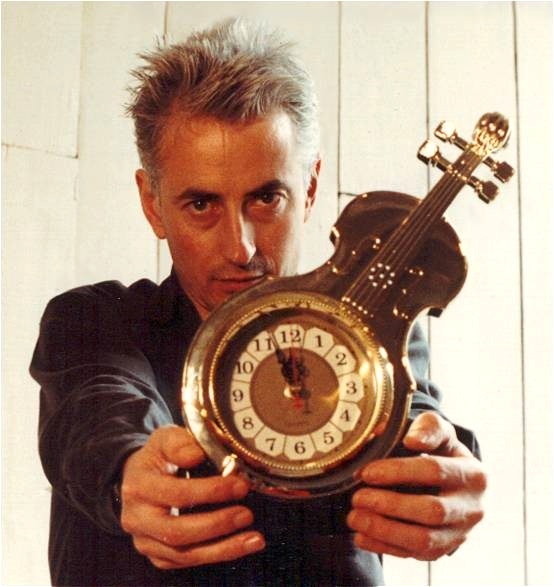

'An ominous thumping emerges from a coffin standing upright in a corner. The black box emits a roar, the door crashes open and the room reverberates with amplified thunder, the wooden casing employed as a full-bodied resonating chamber. The coffin-turned-instrument is just one of the many exhibits on display in The Rosenberg Museum, the private collection of experimental violinist Jon Rose - a bizarre stockpile of violins, violin-like instruments and violin-related paraphernalia collected, invented or built over the course of the artist's career. Violin-shaped liquor bottles cover shelves, coloured violins with inset clocks hang in a row on the wall. A 1970s issue of Life magazine with a young, violin-wielding Richard Nixon on the cover, is on display next to the 'Sex & Music Issue' of Playboy from 1998 featuring Linda Brava posing seductively with a white violin. A pedal powered violin is displayed next to a kind of musical surveyor's wheel. It is among these exhibits - the first time the collection has been displayed in Australia - that the second instalment of Music in a Time of Dysfunction takes place. On one side of the room is a player piano delivering a transcription of the sound of the busy gaming floor at the Sahara Casino in Las Vegas - 'The sound of extremely poor people losing the rest of their money,' quips Rose. He introduces us to the seemingly random notes dribbling out of the piano. The pokies, Rose explains, are tuned to C major and while the notes sound haphazard, over the course of the performance the key area provides a point of stability. In the centre of the room is the robotic Data Violin, which turns trading activity on Wall Street into music. Mechanical hooks line the side of the instrument, each 'finger' representing a company; the longer the tones are sustained, the more money is changing hands. The performance begins with these two instruments: music generated by the sound of money. Sparkling flourishes from the piano-poker machine payouts adorn the huskier, drilling sounds of the Data Violin, 'billions of dollars going down the plughole.' As Rose points out, 'They talk to each other.' The lights dim and the performance shifts gears, Rose shoots out a single violin note, illuminated by a standing lamp that clicks on and off in synch. Robotic instruments - the SARPS (Semi Automated Robotic Percussion System) string quartet controlled by Robbie Avenaim - add a rattling voice to the mix. A junkyard organ warbles softly. Rose spins bright flourishes from his violin while Clayton Thomas imitates the hammering robot string quartet on his bass. The Data Violin seems, impossibly, to respond - as if the players are influencing the trade on Wall Street with their music. The piano and Data Violin are switched off and the players ride their own momentum, Rose's frenzied fiddling a sinister hoe-down while static hisses through speakers and the robot quartet jackhammers away. Thomas produces soft harmonics while Rose's violin emits a far-off screaming that becomes a guttural roar. The lid of the coffin [Jon Rose tells the editors that old style violin cases were commonly called coffins] bangs open and shut, an onslaught of percussion while the amplified string inside growls. With a shout, the lid swings open to reveal an ashen white figure. Dancer and choreographer Tess de Quincey, ghostly white, completely naked, wails and screams, slamming the lid and convulsing as if electrocuted.

She fills the room with wild ululations - Rose's violin screaming in sympathy - as an arm and a leg emerge, cabaret style, from the coffin, lights strobing. A number plate wedged into the double bass's strings sends splintering white-noise through the speakers and De Quincey screams at the audience before she leaves the coffin to walk out through a green-lit Exit, the coffin generating a residual hum of feedback that bathes the audience before Rose cuts it off. Music in a Time of Dysfunction - Part 2 emerges from and recedes back into the Rosenberg Museum exhibition as if the strange, experimental instruments have all come to life on their own. The result is a chaotic experience of a performance that embraces experimental sounds infused with a critique of contemporary life and capitalism, alongside kitsch, Halloween playfulness. Rose has indicated that this may be the last time the collection is displayed and the exhibition definitely has the feel of a retrospective. A room off the main space displays footage from Rose's bicycle and fence projects and the museum's guide-book is full of reminiscences. An anecdote about being stopped by the border guards between East and West Berlin and made to explain his 19-string cello - the unusual number of strings disqualifying the instrument as a cello in the eyes of the suspicious guards - is a kind of comic microcosm of Rose's practice as a whole. But while The Museum Goes Live might draw a line under one part of Rose's career it is by no means an ending. With the violinist having recently been awarded the Peggy Glanville-Hicks Residency for 2017 there is no doubt we will be hearing more of Jon Rose.'

Realtime Magazine

'In the company of visionary musician audio pioneer and provocateur Jon Rose, anything can happen. Audiences at his mysterious Rosenberg Museum of the violin have encountered bicycle-powered and robotic instruments, dust for violin and flies, and a musician sawing up violin cases then putting them in a blender to make marmalade. 'The mayor and his wife had arrived hoping for Mozart,' Rose says of that performance. 'They spent the concert with their backs to the wall, waiting to make their escape.'

For four decades, the museum and its vast collection of 800-plus eccentric hand-built instruments, violins and violin iconography amassed by Rose have resided in a Slovakian town called Violin (improbably but true). Now the whole caboodle has travelled to Sydney, where Rose and some of Australia's finest experimental musicians will bring it to life in a series of nightly performances from October 30 to November 6 at Carriageworks, where the collection can be viewed by day. Expect to see a female dancer playing a real coffin (equipped with a single string) from within, and Rose playing a fence with a violin bow. 'I call it the museum that messes with your mind,' a gleeful Rose says. 'I want people to leave thinking: what the f--- was that?'

Despite his humorous anarchy, Rose's work and his outlandish instruments are no stunt. The music he coaxes from them is beautiful, haunting, and acclaimed globally. His fence music, which has been performed with a violin bow upon the world's greatest and politically symbolic fences - including about 30,000 kilometers across Australia - is layered with messages about humanity.'

Sun Herald

'Every Sydneysider knows what the Harbour Bridge looks like, but Jon Rose must be one of few people to have considered the sound of the iconic landmark. In one of his latest projects the veteran experimental musician and violinist - who has spent a lifetime looking for music 'where it's not supposed to be' - has attached microphones to the bridge. 'When it heats up and cools down the whole thing makes these huge bangs and crashes you never hear because of the sound of the traffic,' he says. 'It's just full of these sonic events. There's also the traffic on the bridge and then there are these high, long sustained sounds which sound like wind but aren't - they are the traffic resonating through the bridge as well. However, 'listening' to the bridge in this way is not without its practical challenges, including attracting unwelcome official attention. The police come along and see all these cables and shit and think you're going to blow it up," says Rose. When he has collected enough recordings Rose will turn them into a vocal work. It's one of the projects he will getting to grips with during his year as the 2017 Peggy Glanville-Hicks resident. Under the terms of the award, announced this week, Rose receives $20,000 and the opportunity to live and work for a year in the Paddington terrace bequeathed by Glanville-Hicks. The award comes just as Rose and his partner, violinist and composer Hollis Taylor were considering leaving Sydney for Alice Springs. 'But now instead of moving out of Sydney we are moving right into the jaws of the beast,' he says. 'Real estate hell - except we're not paying for it! It's very exciting. I'm really delighted because I do actually like Sydney. I just can't afford to be here. 'Currently, Rose is staging a combined exhibition and performance at Carriageworks, part of the venue's Liveworks festival. The exhibition is a reflection of Rose's lifelong obsession with every aspect of violins and violin playing. The items on show are all from his private collection and range from the quirky (an automatic string quartet) to the downright bizarre (a replica of the penis of legendary violinist Niccolo Paganini). Many of the exhibits are the result of Rose's restless tinkering with violins, creating new instruments such as the Data Violin Robot, which 'plays' data generated by trading activity on Wall St. 'It's the sound of money,' says Rose of the curiously disturbing sound generated by the Heath Robinson-esque device. However, Rose believes this is the last time the collection, dubbed the Rosenberg Museum, will go on show. 'It won't exist any more after this,' he says. 'It should have a permanent home but I can't find anybody. It's just too weird.'

Sydney Morning Herald

'Featuring Jon Rose on violin, tenor violin and 'The Bird' (a tenor Hardanger' violin) and Chris Abrahams on Steinway grand piano Model L, these six pieces were recorded live during Rose's Peggy Glanville-Hicks House residency in 2017. Peggy is a showcase of two of Australia's finest improvisors. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the sensitive interaction of both players is a defining feature of this music. Almost as an introduction to this modus operandi, Abrahams only plays single notes on the first piece, Peggy 1, a move that seemed like a conscious decision to not 'outweigh' the single notes played by Rose. Of course, later in the album Abrahams does play much more densely. And so does Rose. But listening to Peggy I was constantly impressed by the way both musicians blended the articulations of what they were playing. On Peggy 3 this togetherness takes the form of a hyperkinetic collection of strummings, tappings and twitterings. There are some wonderful moments where one player is sort of accompanying the other - such as on Peggy 5 - but time and again this album returns to the theme of togetherness and unity. One is constantly struck by the focus and attention exuding from these two players. While this type of thing is easy to witness during a live performance, we can hear this close and virtuosic 'listening' in every moment of this album, an achievement that I think all recordings of improvised music aspire to... It could only be made by these two master improvisors. Highly recommended.'

Music Trust Magazine

'Swirling around glissandi, cadenzas and key clanks and clips at speeds ranging from moderato connective to showy, multi-key, pseudo-ragtime, Abrahams makes the perfect foil to Rose's string swagger. Spraying staccato lines at incredibly high pitches, double stopping, sawing and moving onto thin spiccato runs, the violinist hardly pauses between one swift string slash and the next. By 'Peggy 4', the two have come up with a working aural definition of post-modern music. As Rose abrasively scrapes unusual textures from what's probably a Hardanger fiddle at a high velocity, the pianist's tremolo patterning skips along in a contrapuntal manner. Finally Abrahams uses a waterfall of notes to modify the fiddler's dissonance, so that as his patterns gallop from the bottom of the keyboard's range by 'Peggy 5' he has made common cause with Rose's stops and shuffles...Not anything to play for fanciers of conventional piano-violin duets, the sheer intensity of this duet shows why both players are experts in communicating improvised music.'

Jazz Word

'Two musicians who have known each other for forty years, committed in a lively overall study, made of popular excerpts, contractions, pauses and compact blocks. The action of the strings of Rose, constantly feeding independent and specular melodic lines, Abrahams, intesser and structuring, reactive and flexible tonal grids on which the writhing cords are treated as graft. A game of overlapping planes broken and changing, with the shrinking of the third movement and the clouds coming in on the sixth over everything. An admired exclamation of applause is a logical final.'

Kathodik (Italy)

'The collaboration of two musicians who have been known each other for decades has resulted in half a dozen major piano compositions and unorthodox tuned strings effectively snapping their tone and counterpoint with their main concern by pushing sounds to the edges as conventional instruments sound more like electronic and industrial.'

Periodiko (Greece)

'In residence at Peggy Glanville-Hicks House in Sydney for a year, violinist Jon Rose presented several concerts, including one with fellow pianist Chris Abrahams, immediately completed by another the next day in the same company. It is strange that these two musicians did not think of dialogue earlier in their long career, as their duo goes without saying and often exceeds the addition of the two instruments to form a hybrid whole, and this is particularly true when the piano and the violin are percussion instruments. Jon Rose uses several violins including the one he calls 'the bird', equipped with sympathetic strings. The two musicians deploy in every room an extended but never demonstrative vocabulary, which takes pleasure in being outside the habits of harmony and tone imposed by the rules of harmony of Western music - so that some people's ears may feel assaulted by the unusual relationship that Jon and Chris bring into play. Prepared piano, struck violin, acid, semblances of melodies, sudden whirlwinds, everything goes, without ever, once again, that the game employed does not screen common speech, remarkable.'

Revue et Corrigee (France)

'The Rosenberg Museum is an unstable mixture of factuality, false attribution, music history, twisted aesthetics and humour. It blurs the lines between reality and fiction that even direct participants in this project are at times unable to discern.'

Arts Review

'IIn the late 1920s, Shostakovich was given a challenge to re-orchestrate the then-recent 'Tea for Two,' which he was supposed to complete in under an hour. Fast forward nearly a century, and when Rose and Curran get their hands on it, they bring a new meaning to the word arrangement. Quarter-tone-inflected pianos in impossible registers bolster and buffet Rose's sentimentally warbling saw, destroying all, or most, sense of pitch, tempo and swing as the inevitable bric a brac conclusion invades, like a virus. Fans of Art Tatum should take note, but the two-minute historical and stylistic distillation is only the tip of the iceberg. Curran gets a chance to plumb the misty depths, evoking all from Miles Davis to Bill Dixon but on shofar, while Rose provides droning accompaniment via three-meter drainpipe with strings. Even these fairly streamlined arrangements provide quite a sonic feast, beautifully recorded as they are, but they don't prepare for the full-on assault of an epic like 'Adorno's Boiled Egg', which opens the disc. Sure, it all starts out close to civilized, but the piano and violin interplay (or is it some sort of lower-register violin?) soon breaks off and is then shredded by technoscreams on a vast scale. As it turns out, all elements are merely developmental components that are gradually superimposed and dropped willy-nilly around the soundstage. We get beats, scratches, tonality and whatever its opposite might be in dizzying arrays as distorted clangs and drones gradually pervade all, all that is until a sudden and nearly sickening stop brings unexpected silence.

What's the point of spoiling the fun? Those in search of something like this will know from reading this far. Headphones are recommended, as, despite nearly incessant confrontation, the duo makes room for moments of beauty and subtlety, as on the quietly tail-chasing interplay commencing 'The Marcuse Problem.' The disc demonstrates undimmed invention and insatiable sonic searching in tandem, and the ride is well worth taking.'

Dusted Magazine

'But the playing, with Rose's violin skittering dangerously around and Curran in his self-declared cocktail pianist mode, is positively playful. How two men whose combined age is around 150 manage to generate so much sheer energy is a minor miracle. For all his association with Musica Electronica Viva and other pioneering improv situations, Curran quite naturally settles into grooves, and Rose comes on like he is playing at a wedding. 'Shofarshogood' features that instrument in a short poignant ballad that could equally serve as a Kraken's love song or a lament for the lost and the dead, and one of the genuinely moving and provocotive things about Café Grand Abyss is not knowing whether you're meant to smile or cry. These are two musical flâneurs, observing society and recent history but not at the usual saunter. Associations race past...but basically it's a violin and piano album, an impeccably classical combo that never, ever, even in Beethoven's hands, shook off its café society associations. That's what makes this record great. It takes its pleasures seriously, and it makes its deeper musings seem as light as mousseline.'

The Wire

'There are many crazy interactions here, hardly a surprise knowing these two plays are gifted improvisers. They play intensely, quietly, minimal, maximum, joyful and sad, atmospheric and vivid. The samples of Curran are weird and hard to place. In the Rome recordings, this brings some fifty minutes of call and response, whether or not it is intended and some fine music. The Sydney pieces, eleven minutes in total, are a different thing. It is some fake bar music that they meltdown and re-shape radically. Not strange since both musicians worked in bars and restaurants to earn money in their younger years and here and here show off how not to do it properly but at the same time improve quite a bit on it. There is some excellent stuff happening here.'

Vital Weekly

'In addition to the celebration of all things Wesley-Smith there were some additional performances that came as a welcome surprise. Violinist and composer Jon Rose improvised a kaleidoscopic cacophony of light, heavy, beautiful and distorted sounds whilst he recounted memories of his experiences performing with Wesley-Smith at the Centre de Georges Pompidou in Paris.'

Limelight Magazine

'The 6 pieces by Café Grand Abyss are clearly to be assigned to the areas of contemporary music and free jazz. The main instruments here are the violin and the piano, which carry all the pieces and also ensure that the experimental eruptions always return to a song-like garb. Overall, the two set a variety of exciting and very experimental sounds, but you always manage to keep a certain structure and direction. Quiet and melancholic parts of violin and piano knit reassure the high-boiling sound experiment again and again and thus ensure a good flow of the album. An exciting and not overambitious work with a good mix of melody, atmosphere and exuberant experiment.'

Musik an sich

'The Rosenberg Museum: Violin Generator. The three-part composition, based on tone C, uses the prescribed interaction between the six stringers, sitting in the background in the semicircle, and the centrally placed WEB, which sometimes plays automatically, is sometimes provided with 3 percussionists. In individual parts, the WEB is illuminated with different colors, and the strings also trigger the lights with the pedal switches according to the exact instructions in the score. But it is not cheap spectacular performance, but chaosmic music for our fluid time, in which reality blends with fiction beyond recognition. The biggest compliment for both the organizers and the project participants was therefore the disappointment of one of the viewers: 'Until now, I thought Rosenberg was a fictional character.'

His Voice (Czech Republic)

'Musicians operating in the realm of instant synthesis (this usually translates as finest improvisers) are defined by the ability to exploit the elusive qualities of information overload. What appears as a chaotic, and ultimately insufferable cacophony to idle ears and brains transmits instead a refreshing sensation of cosmic clarity (ha!) to people capable of sight-reading the profound score of legitimate diversity. When artists turn a plurality of discordant trajectories into a rational explanation, the unprejudiced witness instinctively knows that something special is happening. Jon Rose and Alvin Curran have so much experience in the sonic field that even hinting at a fragment of their curricula sounds ridiculous. We're discussing performers who, among innumerable projects, have extracted consequential music from marine foghorns (Curran's Maritime Rites) and barbed wire fences (Rose and Hollis Taylor's Great Fences Of Australia). Meaning that these gentlemen belong to the scarcely populated category of humans who were born in sound. For them, there's no difference between a piano sonata, a ritual chant, an exchange of complex phrases on any given instrument, a troubled TV preacher, an industrial clangor. Regular folks making noise through their sheer nonsensical presence can sometimes be accepted as a part of the wholeness, if one's tolerant enough. For the circumstance, the duo focused on improvisational structures for piano, sampler, shofar, violin, amplified tenor violin, 6-string drainpipe (!) and singing saw (!!). In the press blurb, Curran describes Café Grand Abyss as an imaginary place after enlightening us about the recurrence of cocktail pianist elements in otherwise non-figurative ways of approaching the improvisation. If imagination sounded so vivid for every being on the planet, most problems deriving from faulty minds would be solved once and for all.

Each event is meaningful: as time unfolds, infinitesimal occurrences specify a transition towards the truest conception of harmony. The latter is an abused term in the mouths of the ignorant, and this writer is getting increasingly reluctant in using it. However, having scrutinized a track named 'The Marcuse Problem' the lingering feeling is that of standing extremely close to the polyphonic quintessence of everything we hear, feel and live while realizing - yet again - that nothing can be pinned down by a pitiful description. In this record, intricacy rhymes with poetry. Virtuosity is a waterwheel refracting the sun rays of a superior counterpoint typified by an impressive speed of response. Nonetheless, the interplay is entirely deprived of egoistic issues and purposes, positively influencing the listener's mood. This melange of reminiscence, quick detours, lyrical openings, animal agitation, crumbled meanings and ironic covers - check 'Tequila For Two' - attests an acoustic (and mental) pliability that can only be yielded by a lifetime spent investigating resonant molecules, whatever the source. The necessity of so-called communication that has brought countless weak souls to relinquish silent listening to privilege analphabetic intellectualism and enforced social gathering is all but forgotten.'

Toneshift

'It's when you get to the QuickTime videos and suddenly we have a visual element that it all starts to make sense. The footage of Robin Fox and co riding bikes fitted with everything from guitars to record players and literally the kitchen sink in Pursuit says it all. It's sonically interesting, visually head scratching, freakishly creative and utterly stupid. Then there's the violocycle that Rose rides in a velodrome, creating this amazing elongated moan. It's truly a beautiful sound. He plays fences, somewhat hyperactively on the Wogarno Fence, creating almost electronic textures via his extended technique, that he approaches with the rigour of a concert hall performance. But that seems to be Rose in a nutshell, whether he's duetting with flies by scraping his violin across a window, using a kobelco front end hoe excavator with a minimum 250 kilo loading, a midi controller bow, a quadraphonic k-bow, a violin record player, or a 19 string cello, he does so with boundless creativity, curiosity and focus. Rosin collects some of Rose's unique musical obsessions over the years. It demonstrates a unique personal vision alongside an endless curiosity about tradition, social convention, and cultural icons. He's not just using music to make sense of the world, but constructing pieces of music offering equal parts humour, absurdity and insight, that ask us to reconsider our own relationship to sound. A true musical icon.'

Cyclic Defrost

'Overall, the two (Curran and Rose) set a variety of exciting and very experimental sounds, but you always manage to keep a certain structure and direction. Quiet and melancholic parts of violin and piano knit reassure the high-boiling sound experiment again and again and thus ensure a good flow of the album.'

Trans German

'Of all the many wonders of free improvisation, perhaps the most extraordinary is the way the music places itself beyond the confines of time. This happens both in the moment of creation, and, if recorded, on playback. Transient time, as we know it, ceases to exist, to be replaced by an infinite series of instants of now, and this immediacy gives the music its remarkable sense of eternally lying outside idiom or convention. It could have been made 50 years ago, yesterday or deep into an opaque future. But for this suspension of chronological time to occur, the music must have the throat-gripping intensity that it does here. Alvin Curran (piano, sampler) and Jon Rose (violins and assorted other bowed devices) seem to expand your mind and ears as they stretch musical possibilities beyond accepted elasticity. Where most artists of any sort work within defined aesthetic palettes, Rose and Curran keep re-contextualising each other's sounds, so beauty is subverted and subversion is sanctified. My own levels of surprise, alarm, amusement, enchantment and exhilaration actually increased with successive listenings. Factor recovery time into your schedule.'

Sydney Morning Herald

'Two masterful, virtuosic and inquiring musicians - Alvin Curran on piano, sampler & shofar, and Jon Rose on violins, 6-string drain pipe and singing saw - in an incredible album of improvisation that seems to know no boundary, farcically claiming to be revisiting their earliest experiences in cocktail club bands, but instead shredding the concept with breakneck speed and surprise; wow!'

Squidco

'Yet the charm of the song of birds, nature’s first musicians as Olivier Messiaen called them, mingled with music in seven recent Australian pieces, did not fail. Most magical was Hollis Taylor and Jon Rose's Bitter Springs Creek 2014, featuring Taylor's recordings of pied butcherbirds in the MacDonnell Ranges. The year is an important part of the title since Taylor has established that not only is it possible to identify individual birds by their calls but that those calls evolve over time.'

Sydney Morning Herald

'Jon Rose, comes from a long line of 20th century artists, from Dada through Fluxus, who poke fun at the seriousness of modern music or art while making us question what is music? Mr. Rose does not just play the violin, having long manipulated a wide variety of stringed instruments as well as non-instruments like fences, bicycles and saws. Over three CDs, Mr. Rose explores and presents a wide variety of mostly Australian artists: street & folk musicians, a department store pianist, an Aboriginal ladies choir, chainsaw & bowed saw orchestras, too many other oddities to name here. Throughout more than fifty tracks (nearly three hours), Mr. Rose presents a wealth of strange and wonderful sounds: music, voices, some unadorned and others messed with. The datadisc is not a DVD but can be played on your computer's Quicktime video program. Since a great deal of what Mr. Rose does is visual, this disc shows many of the unique instruments and hybrids like the 19 string cello, a barbed wire fence, the bowed saw orchestra, the burning violin, a violin record player and the viocycle. Watching Mr. Rose be apprehended by a security guard for playing solo violin in front of the Sydney Opera House, is pretty amusing in itself.'

Down Town Music Gallery NYC

'There is a visible tendency towards minimalism, noise and jazz here, but this musical encounter might perhaps best be described as maximalist. Just when you think the parameters are aligned, an unexpected reversal occurs. We are embarking on another journey - extroverted and joyful, followed by the sudden appearance of darkness and wonder. The creators of Café Grand Abyss imaginary space Jon Rose and Alvin Curran continue their collaboration started in 1985 in Berlin, with this piece of music that is neither as comfortable nor 'old-fashioned' as the CD title might suggest and based on the experiences of contemporary academic and experimental music. They use elements that relate to concrete, spectral or sonoristic music. The compositions are based on modern concepts, innovations, inventive musical decisions, vital expressions, and complicated structure.'

Radio Belgrade

'Seasoned music experimentalists, American Alvin Curran and Australian Jon Rose, take the listener on a wild ride around the free improvisation cabaret circuit...By contrast many of the sampler elements of Benjamin at the Border involve recognisable instrumental elements such as percussion, brass and vocals, and the violin playing is insistently frenetic. For the most part the textures are relentless including the duet between violin and piano occurring about a third of the way into the performance. However what follows is a slow and contemplative interaction between violin and piano which gains momentum with the addition of a complex and aggressive sample collage. There is welcome grand pause before a rhythmic groove begins and builds. The track ends with sustained sample elements overlaid with skittish violin gestures. There is a marked change of pace with Shofarshogood, a short track featuring Curran's slow and highly decorative shofar solo accompanied by drone-like textures from Rose's home-made 6-string drainpipe. For me this improvisation is the highlight of the release.'

Music Trust (Australia)

'Jon and Alvin on terrifying form: Alvin spookily surefooted in his deployment of an often-counterintuitive palette of sounds, and Jon just brilliant. Living legends: Alvin recently left 80 behind, Jon is facing down 70. The two have known each other since 1985, when they were both living in Berlin, and they've worked together on and off ever since. On this CD they look back to their earlier careers, when they were gainfully employed in bread and butter club bands: Jon in the house band of Club Marconi in Sydney where, in addition to playing Italian favourites and film music, he backed funky soul singers and topless go-go troupes, and Alvin, who says: 'So embedded is the cocktail pianist in my music, there are times when I think in medium bounces, or up-2's, slow 4's or Viennese 3's with the accent on the delayed 1, offset by single triplet rest.' Curran doesn't scratch or filter his samples but takes them straight; it's the choice of the samples that leads away from the main path. Rose responds - or ignores - with regular and amplified tenor violins. And when Alvin reaches for the Shofar, Jon picks up his 3-metre drainpipe with strings. And did I mention the singing saw?'

Forced exposure

'That happens in full in the interplay between Curran and Australian violinist Jon Rose. Rose has the other's floor. Here, two veterans have tested the party ends of the violin countless times. And even now he continues to do that with full dedication. Ironing, hitting, tapping, grinding, and if necessary a peasant dance. Curran flies over the keyboard with fingers, wrists and elbows. Turns some buttons to make equipment scream. Rose does not move far behind, and presses his effects pedal under the floor. Two veterans have built a party here that is unparalleled. Party animals up and honk.'

Gonzo Magazine (Holland)

'Together, the two musicians (Curran and Rose) create a musical world far from being as cosy and vintage as the albums artwork suggests it to be with the opening composition 'Adorno's Boiled Egg' bringing on a hard to swallow information overdose whilst incorporating influences from (Neo)Classical / Contemporary Classical, Free Improv, FreeJazz, bar piano, feedback-oozing Noize, experimental cut-up music, HipHop- sampling, Dada and way more - within a total playing time of a little more than 12 minutes only. Which is an awful quite a lot to take in in this short amount of time. Following up are five additional tracks of similar intensity, meandering in between extremes whilst bringing joy and thrill to the most advanced of the advanced listeners whereas other might give up due to the multilayered complexity and seemingly chaotic, yet structured but extremely demanding nature of this longplay piece. Give it a try if you dare.'

Nitestylez (Germany)

'Dramatically intriguing, The Marcuse Problem is built upon thickening a narrative constructed from angled fiddle runs and keyboard clinking to reach such a level of echoed intensity that it appears the pressure can't be further amplified - and then it is. Finally the theme is deconstructed, leading to an appealing conclusion. '

The Whole Note (Canada)

'Jon Rose is extracting wide range of timbres and tunes – from elegant and soft, tiny and sweet to rough, aggressive, sharp, dramatic, weird, murmuring, scratching, noisy, screaming, waining, shrieky or low, dreamy and solemn. All wide palette of timbres is extracted here – musician creates a colorful and rich texture, expressive musical language and gorgeous background. He's open to new ideas, interesting combos, exotic rare tunes and modern innovations. His instrumental section is completely based on extended, rare, experimental and innovative ways of playing, special effects, modified timbres, research of strange tunes, expansion of technical abilities and fascinating sonoristic experiments. Dramatic, bright and luminous culminations are full of thrilling exciting solos, expessive vital melodies always accompagnied by textures, ornaments and expressions of all kinds. It's also the source of awakening ideas, experiments, modern expressions and the basic of driving, colorful and independent melody line. Synth tunes, electronics, computer sounds, ambient, drone, out-puts, in-puts, glitch, sonoristic experiments, field recordings and other similar playing techniques are beautifully mastered by Alvin Curran.'

Avant Scena (Italy)