Ghan Tracks

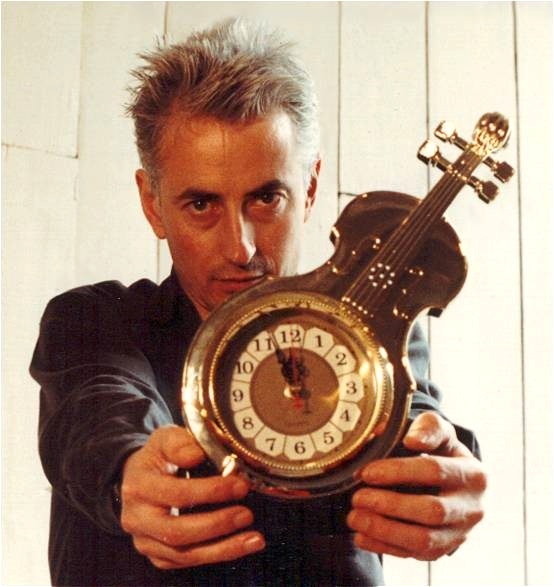

a project from jon rose

Ghan Tracks situates itself somewhere between a multi-media performance, an installation, live radio, and a documentary. It is above all a meditation on the notion of progress that underscores the Australian story with all its assumptions, optimism, conceit, miscomprehensions, and failures.

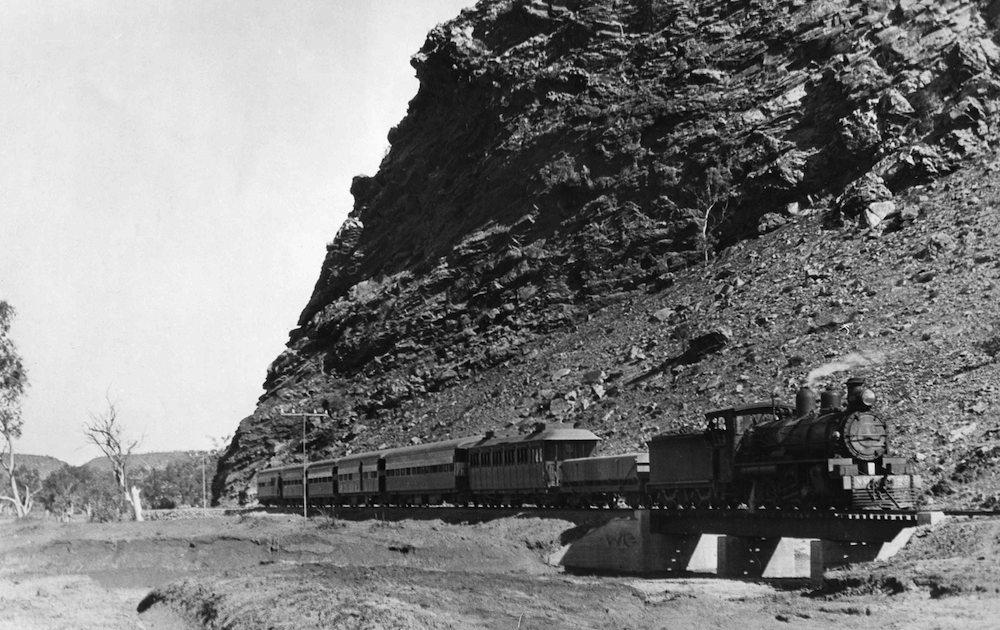

The present day Ghan is one of the world's great train rides, running as it does nearly 3,000 kilometres from Adelaide to Darwin; it was finally completed in 2004. The story of the building of The Old Ghan from Port Augusta to Alice Springs (1878 - 1929) and its final demise in 1980 is, however, a story that takes us on a journey through a collective memory of what it means to live on this continent, what we take, and what we cannot have.

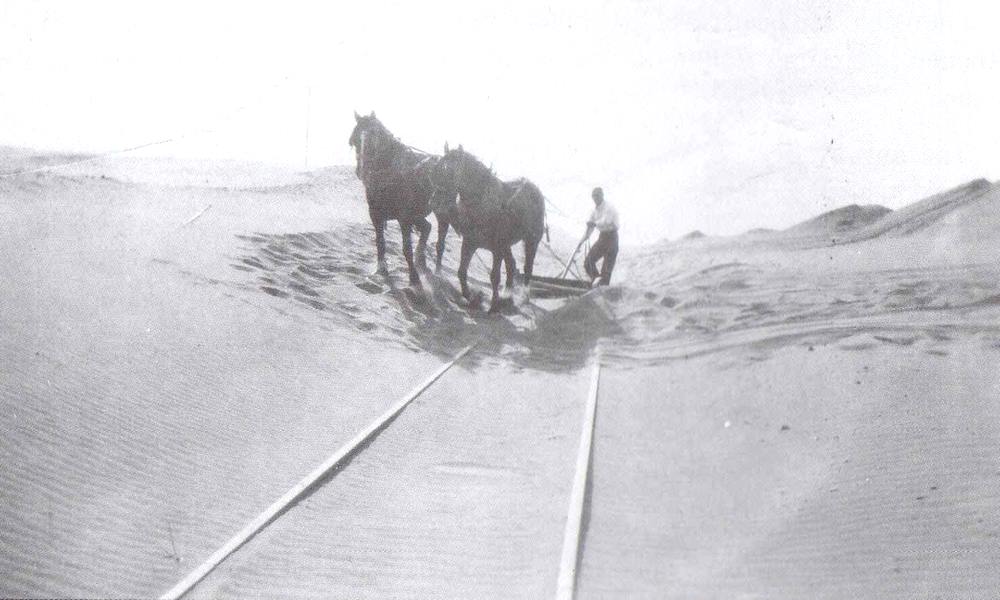

Once, The Old Ghan famously arrived three months late in Alice Springs, the train having been delayed by floods in its cross-desert ramble from Adelaide. As we know now but did not then, rivers in outback Australia remain dry sometimes for decades, and then suddenly it rains - a lot. The original Ghan was notorious for washouts on one hand, and the bewildering and belligerent arrival of sand dunes over the track on the other; the flatcar immediately behind the tender carried spare sleepers and railway tools, so that if a washout or sand drift was encountered, the passengers and crew could work as a railway gang to repair the line and permit the train to continue. As you can read in the Train Timetables of 1949, the top speed allowed for the Ghan was a massive 32 kph; anything above that was considered dangerous.

When the building of the Ghan was started in 1878, the white population of South Australia was no more than 300,000. The British had occupied Adelaide and its surrounds for a mere thirty years. After the successful building of the trans-Australian telegraph line in 1872, the authorities decided that South Australia would be connected to the Northern Territory and that a railway was required to maximize the great colonial adventure - the assumed potential, the exploitation of central Australia.

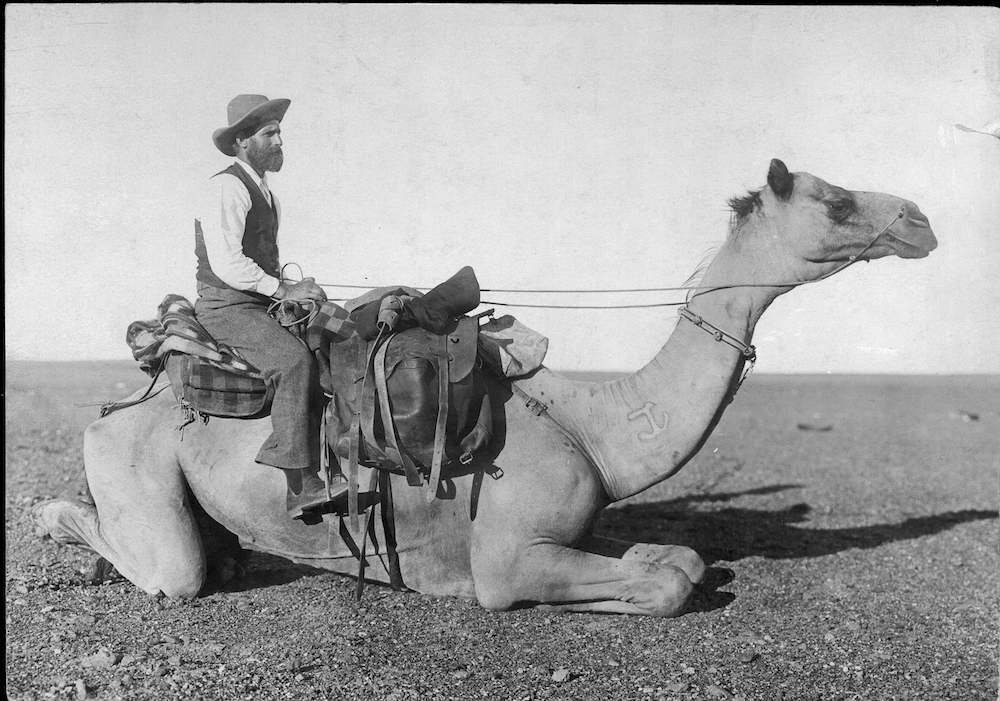

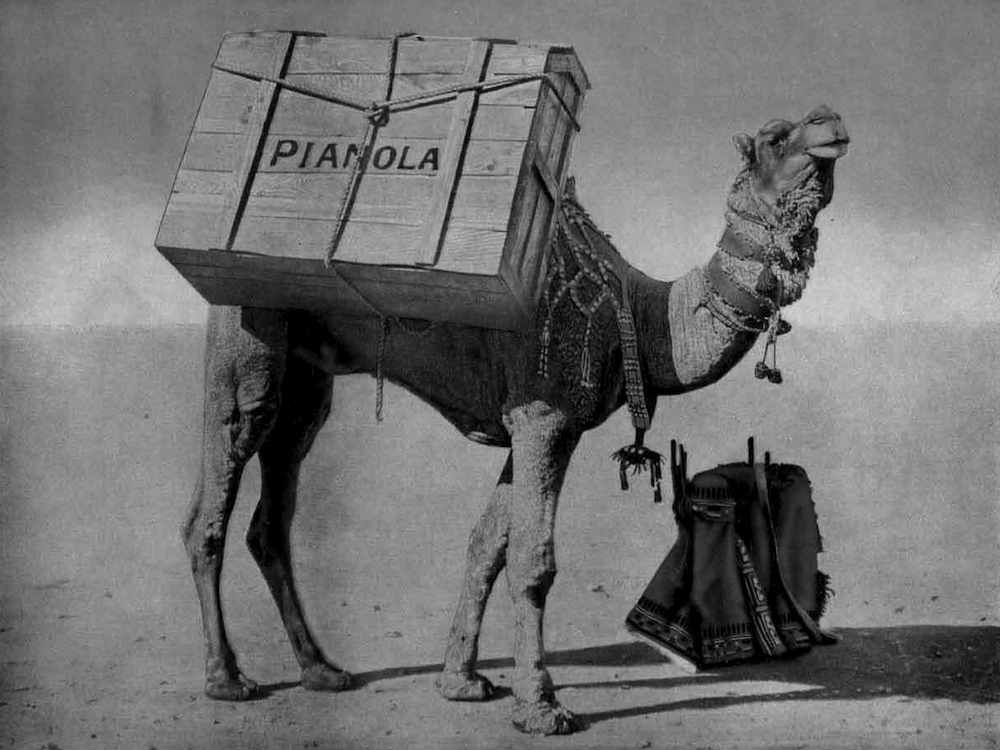

No one knows exactly who gave the Ghan its name. First, it was known as the Great Northern, then as the Central Australian, and finally (as the irony of conceit slowly dawned on the colonialists) as the Ghan - thus downsizing the initial imperial optimism of the enterprise - incorporating flexibility in the guise of willing foreigners who could share the blame and responsibility if it became necessary. The history of the "train to the north" is intertwined with the "Afghans" or "Ghans" who gathered at the newly arrived railheads, wherever they had reached, and with their extended camel "strings" connected the ever-expanding commercial interests of "Centralia" with the coastal populations and empire. The Afghans (actually a mix of nationalities from what is now Pakistan and Afghanistan) with their camels provided and controlled the transportation of goods and artifacts over vast tracts of Australia up until the introduction of motorized conveyance in the 1930s. The Ghans went where the train had not yet reached; one cannot tell the story of the train without referencing the story of the cameleers. Besides, the exotic camel was much more flexible than the railway as an instrument of delivery.

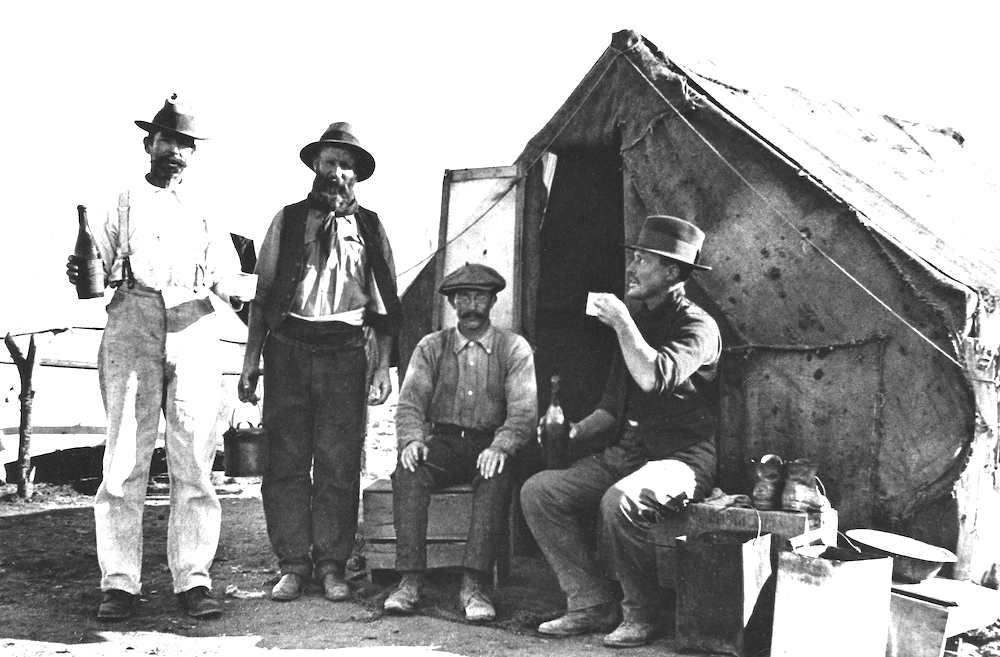

Just the building of the Ghan railway fills the archives with frontier stories of extreme deprivation, levels of hardship outside contemporary perception, spontaneous violence, blatant ignorance, bravery, hilarious stupidity, and environmental conditions that eventually saw the original railway's demise only fifty years after it was finally finished (that is, the link from Oodnadatta to Alice Springs). The final minutes of Ghan Tracks contain video images that show the last Ghan in 1980 fitted with an ingeniously conceived contraption that pulls up the very rails upon which the train sustains itself, and without which the entire venture cannot function or survive. Such a metaphor in the contemporary environmental context in which we find ourselves cannot be more succinct. However, it is too easy, from the comfort of a 4WD, to look in hindsight on the works of earlier generations with a condescending smile - and despair. The pioneers of the tough colonial adventure were, despite the unpalatable racist attitudes of the time, an extremely positive bunch with an amazing ability to survive, improvise, create and entertain, with little in the way of resources at their disposal. How would we cope in such circumstances?

The Arrernte version of the Ghan's arrival into Alice Springs can be heard here as Peter Paltharre relates the indigenous story of the wild dog from the south that comes to destroy their land and culture.

The pdf programme of Ghan Tracks with full texts, credits, and photos can be downloaded here.

A pdf of the Ghan Timetables from 1949 includes some extraordinary details such as how to rig up a temporary telephone to the overland telegraph line in the event of a breakdown - it can be downloaded here.

Ghan Tracks also exists as an ABC radiophonic composition Ghan Stories broadcast on soundproof in February 2015.

The Ghan Tracks Promo can be viewed here.

Ghan Tracks live video extracts can be viewed here.

Ghan Tracks review in Realtime can be seen here.

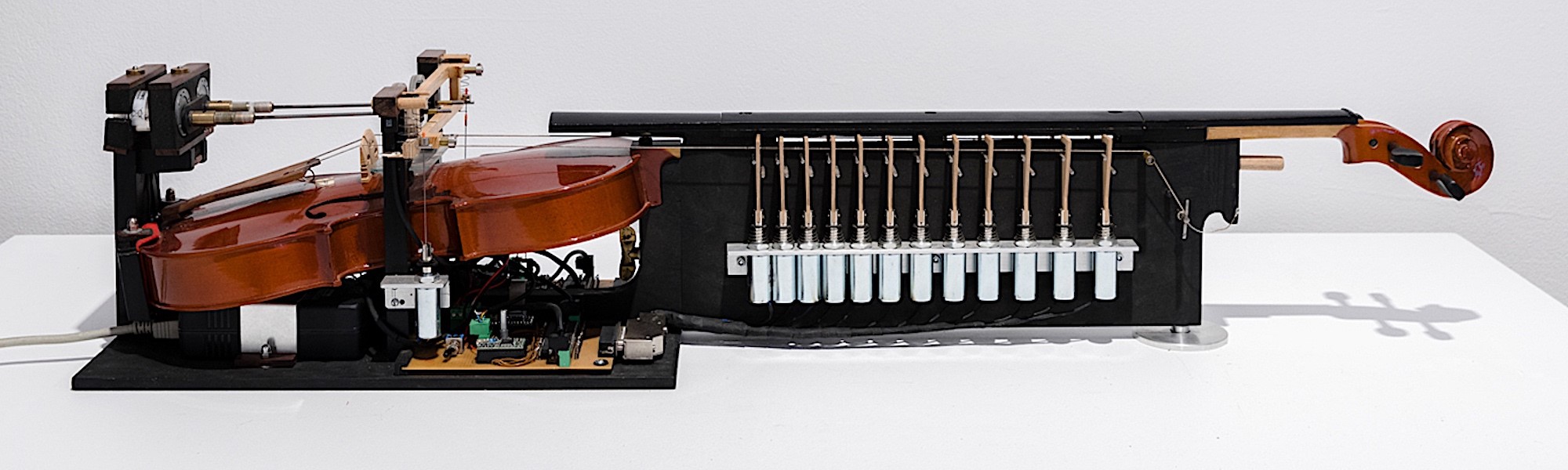

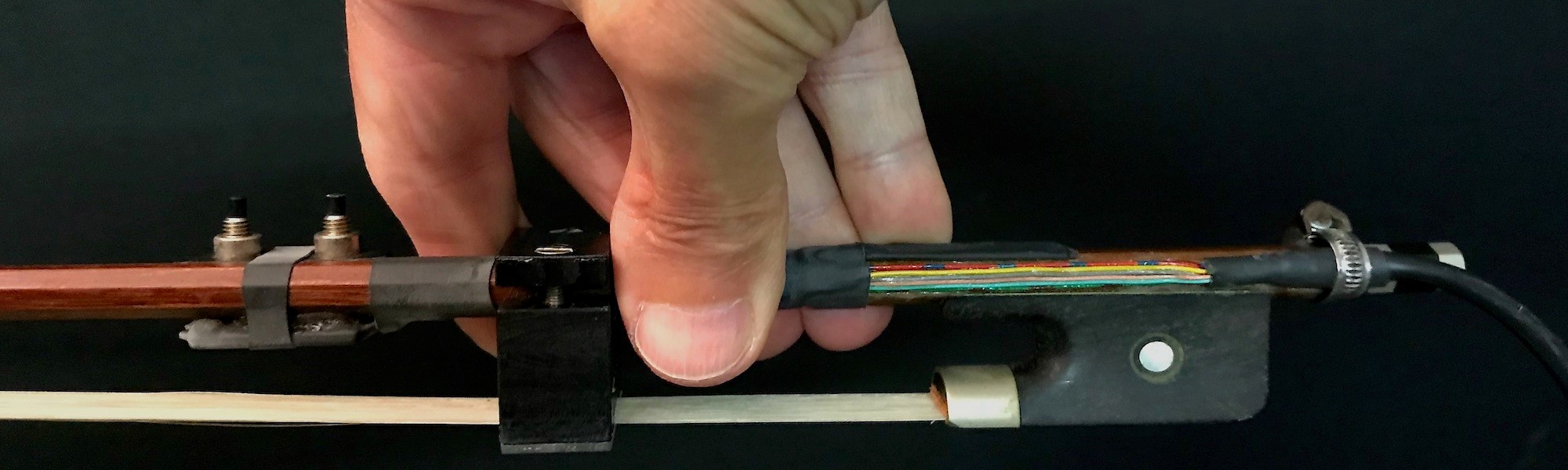

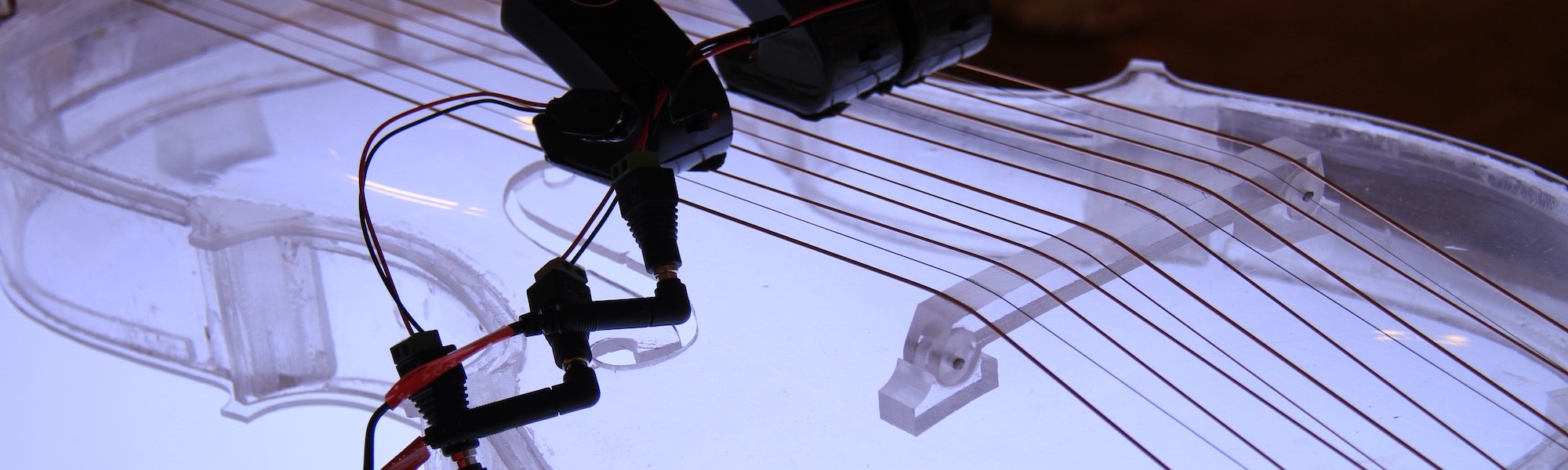

Ghan Performers: Claire Edwardes (vibraphone - equal tempered), Eugene Ughetti (vibraphone - unequal tempered), Jennifer Torrence (percussion, cement mixer, wind machine), Lamorna Nightingale (piccolo, flute), Jason Noble (bass clarinet), Cazzbo (sousaphone), Clayton Thomas (double bass), Damien Ricketson (the plectraphone, wind machine), Lucy Bell (actor), Patrick Dickson (actor), Peter Paltharre Wallis (Arrernte Elder and story teller), Doris Stuart (Arrernte Elder and story teller), Jon Rose (composer, writer, research, multi-media, conductor), Aaron Clarke (production), Jeff Khan (executive producer).

© Jon Rose 2015