Cutting Edge and Corrugated Iron

by Deborah Bogle

Out here in regional Australia, if you want to see classy acts on stage, you usually have to hit the road and drive to the big smoke. (To be fair, local entertainment venues do feature touring performers, and fans of Kevin Bloody Wilson and his ilk need not travel far.)

The red dirt flat outside a Murchison shearing shed might well have been a more likely setting for Kevin Bloody Wilson than for a performance of avant-garde music. Perhaps some of the locals, clearly somewhat bemused by the sight of musicians screaming into their violins, might have been more comfortable with Wilson. If that were the case, they were too polite to say so, and applauded enthusiastically at the end.

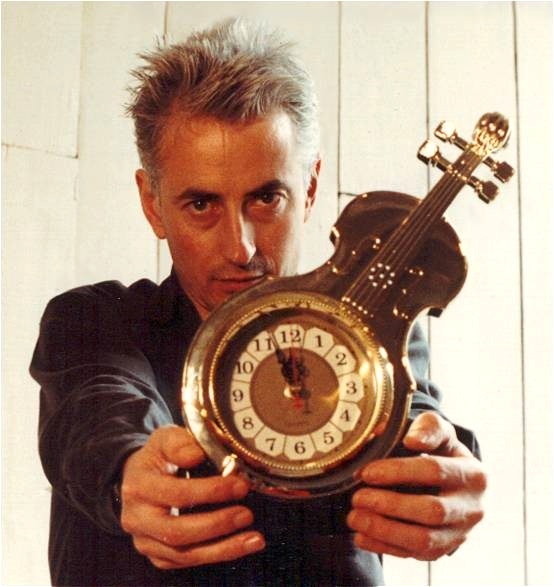

Jon Rose, composer, violinist, and new media artist was still shaking his head in wonderment on the morning of the performance, on Easter Saturday.

"This would have to be the most unique new music experience I know of," he said. As one who performs in Europe and Japan as well as Australia, he's accustomed to having to travel to find the slender proportion of audiences with an ear for the avant-garde. But out there? Amazing, we both agreed.

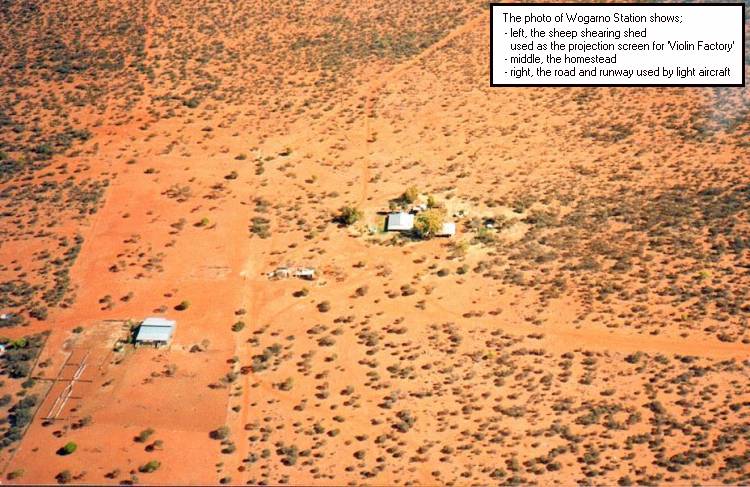

The bush setting at Wogarno Station, south of Mt Magnet and about six hours' drive north of Perth, was part of the Totally Huge New Music Festival's drive to bring new music and its aficionados to "the parts of the land they normally only fly over" (www.tura.com.au).

And so, on Good Friday, we piled our swags and camp ovens and eskies into our 4WDs and headed off to see Violins in the Outback.

Campers who wilted in the 30-plus heat and were driven to distraction by the flies might have wished they had only flown over this land. When the sun was high, shade was scarce, and there was no river or dam to cool us down.

At sunset, the campers gathered with their picnics, as music lovers will do, from Glyndebourne, to Leeuwin, to the Domain, to well, right there in the red dirt of Wogarno.

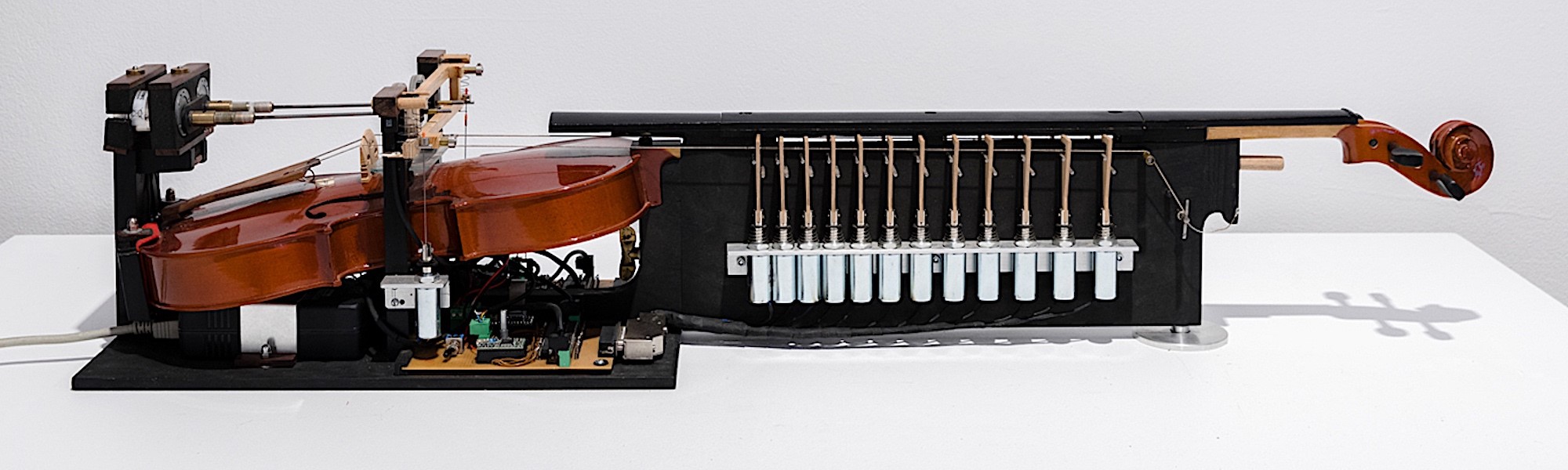

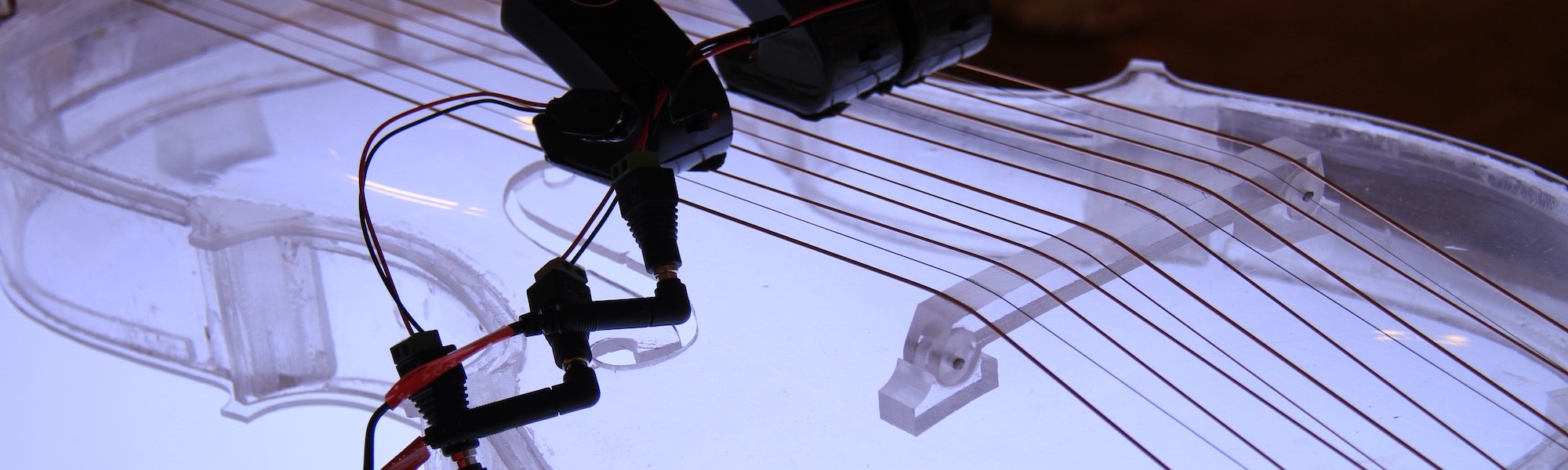

Jon Rose's Violin Factory 2 was the centrepiece of the weekend event. Against the corrugated iron backdrop of the shearing shed, a 22-piece orchestra of violins and a three-piece percussion section performed the hour-long piece. Lilting, melodic passages were followed by cacophonous outbursts, with saw, hammer and various other percussive effects, all punctuated by the exhortations (in Mandarin) of the Red Army guard, urging the factory workers on from her position behind the stage, high atop the loading ramp. Meanwhile, images of modern China and Chinese violin factory workers were projected onto the shed wall.

I've spent many nights in the Murchison, but never one like this. It was extraordinary.

Rose has long been fascinated by the idea of communicating his work to audiences in remote parts of the country, and using technology to allow artists in distant locations to perform together.

The first performance of Violin Factory, in December, 1999, was staged in the Vienna Radiokulturhaus, the concert hall of Austrian National Radio, and was simultaneously broadcast on Osterreich 1, the station's cultural channel, and webcast over the internet to a concert space in Vancouver. There, against a backdrop of webcast images of the performers in Vienna, a group of musicians interacted with their colleagues in Vienna with improvisations that were in turn fed back to Vienna and to the Osterreich listeners. Audiences could also listen in to the performance via web radio station Kunstradio (http://kunstradio.at/).

Rose presided over a similar web-enabled performance, this time a trans-continental one, way back in 1994, in the ABC-FM concert spectacular 'Violin Music in the Age of Shopping', with the orchestra live before an audience in Sydney and the choir in Perth.

Even as recently as the 1999 Violin Factory performance, this was bleeding edge stuff. Why bother, one wonders, when we have existing media - radio and satellite television - that do this kind of thing quite well, albeit at a high cost? Rose shakes his head. Feeding those images across the web was, he admits, "a pain in the neck". Anyone who's been involved in a webcast will be familiar with the stress of trying to maintain a jerky feed via a Net connection, even a high-speed one.

Expectations are high, and disappointment inevitable. Until broadband is widely available, one might just as well save all that creative and technical energy.

Rose agrees. Forget the images. He's most excited about web radio. RADIO was, he says, the first virtual reality, long before the phrase was ever coined. A child of the 50s, growing up in the UK without TV, his love affair with the medium has been long and fruitful. His first access to the radio waves was late one night at a local BBC station in Birmingham. It was short-lived. Management didn't approve of the broadcast - a version of The Archers sound effects, re-engineered to make it sound as though the characters were tripping on LSD.

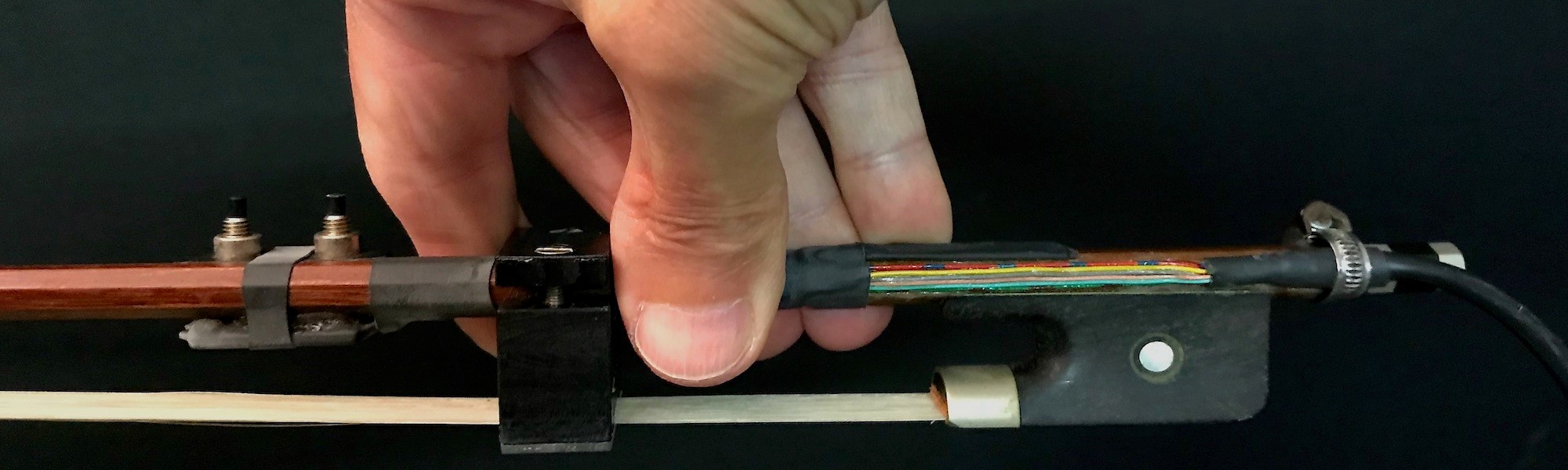

Much later, equipped with a $3 Dick Smith radio microphone built into a cheap Chinese violin, he again gave rein to the audio terrorist within. With a range of about half a block, the mikes broadcast chaotically on a number of frequencies, allowing him to break into his neighbours' living rooms, via their FM tuners, with his distorted violin signal. It was the first version of Radio Violin.

These days, you'll find it on www.jonroseweb.com - not really webradio, but a collection of sound files of his performances. He's measuring traffic to the area - already much higher than expected - and if the figures justify it and he can find the funds, he intends to parlay it into a proper web radio station.

Meanwhile, he continues his longstanding association with Radio National and its avant-garde Listening Room program. He has just completed an artist-in-residence stint there, working on the Australia Ad Lib project, documenting grass-roots, do-it-yourself, improvisation across the country. It will be available as an interactive archive on the ABC's website by August 20th.

© Deborah Bogle, The Australian, (03/05/2001)