the relative violins

questions and answers 3

a conversation between Jon Rose and Hollis Taylor 2001

HT

I don't think non-players realise how different even the standard violins are one to another, for example in timbre, response time, and finger placement. In my composition Trail Mix for five scordatura violins, each in a separate tuning, the challenge was even greater--how to blend them into one soundscape, and harder still, how to find my way around a seemingly familiar territory where the signposts have been changed. Your personal crusade clearly has its roots in history, but is there any history personal as well?

JR

My father made instruments in a Japanese prisoner of war camp for three and a half years, one of few to survive that long. While there a concert pianist asked him to draw a keyboard on a table so he could practice. He decided to make a piano instead. After a year he had gotten two keys working. He made the sound board by trading Red Cross cigarettes for material. The strings were aerial cable. Until I found out about this history, I used to think that I improvised with junk, but it was nothing compared to what he did in those conditions. He was working with next to nothing. The glue was the sludge after the rice had been boiled away. He also made a two-string cello-like instrument. The bow hair came from parachute cable. It was called 'The Little Bastard' because it made such a terrible noise. After one year they had to move camp and he bribed the guards with more cigarettes to tie the piano under the lorry, but the roads were very rough and it fell off before they made it there. He only told me about this after he had seen some of my Relative Violins. 'Oh yeah, I used to do that,' he said.

HT

Most players find four strings to be difficult enough, so why add more? What are the rewards for expending so much time and energy to master these new parameters?

JR

Nothing is as exhilarating as to string up something new that never existed before. It's a fantastic buzz. I have always had a love/hate relationship with the violin. It demands so much, and I have put my whole life into it. I guess I am a workaholic. To glimpse 'the other' is part of my character.

HT

Did this workaholic nature provoke your marathon concerts?

JR

Maybe. In 1980, I started a series of these marathon concerts on the violin to test how far I could go with an improvised language and what would be the effect of fatigue on the music. The first one lasted 12 hours in a suitably-named 'Sound Barriers' festival in Sydney. I tried to play well for as long as possible. I didn't coast. I had to move my position a lot--sitting, lying down, leaning next to a wall. I didn't seize up at all, although my childhood violin teacher had always written on my reports 'Posture is terrible.'

The final marathon that I did was in 1986 at New Music America in Houston, Texas. I played for ten hours, but I had a task. This was to provide a continuous violin sound track to one of the major American TV networks. There I was playing in front of a television set for ten hours, but I can't say that it provided me with much stimulation to keep going.

Back to my old violin teacher, Anthony Saltmarsh, he did have a positive influence on me. He was an exponent of the Knud Vestergaard arched 'Bach bow.' This bow was created to play the Bach unaccompanied violin sonatas and was based on the misconception that the chords in these works were intended to be sustained precisely as written. The bow has a huge arch and is fitted with a mechanical lever worked by the thumb, which enables the player to adjust the bow hair for monophonic playing or, fully untensioned, to sustain all the multiple stops continuously.

HT

That was dealing with the classical problem. In the world of fiddle music, players have been flattening their bridges as a strategy for triple stops, or more extreme, unscrewing the hair from the stick of the bow and placing the hair on top of the strings and the stick underneath the instrument. In such a manner, four strings can easily be accomodated.

JR

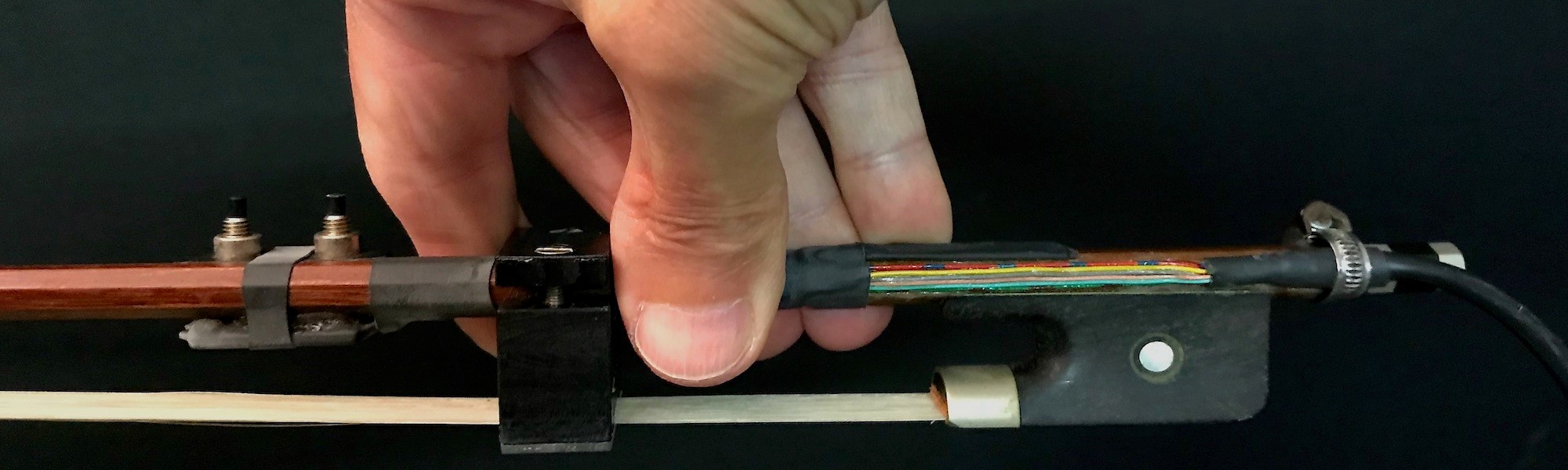

Yes, and they have been doing it for generations. I took all this on board. With help, construction ideas, and heaps of second-hand bow hair from Harry Vatilliotis, I got experimenting with bows. I wanted very short, heavy bows to use as percussion instruments, a bit like a cembalom stick. Often I would serrate the stick itself. This idea was inspired by Paganini who, for contractual reasons, was forced to play a second-rate violin concerto by a certain Valdabrini. Paganini hated the piece so much that instead of a bow he used a reed stick.

In Korean music, they use sticks rather than bows. You get great phasing effects if used laterally. Of course, a lot of anal violin education is about keeping the bow absolutely perpendicular to the instrument. (The Zeta MIDI violin is also designed to ignore or not respond to illegal bowing.)

The bow is much older than the violin, harking back to our hunter-gatherer state. It was and still is a weapon. It is also an ancient and very beautiful musical instrument in its own right. Musical bows, like the African Umuduli, have resonators attached for amplification purposes.

The music, the language of music at its best, is defined by the instrument it is played on rather than cultural expectation or notions of power and control as expressed through western history in forms such as the symphony orchestra. That is the point, that the instrument is central to the music. The primary essence and residue of that exists in the unaccompanied Bach sonatas and partitas, where the sonic strengths and limitations of the instrument are as critical to the musical expression as are the actual notes themselves.

In oral traditions of music, such understandings are axiomatic. The gong and key metallophones of the gamelan are tuned finely but quite freely by the bronze smith instrument makers themselves, who are regarded as wizards who bring sound into existence. No two Javanese gamelan sound the same or are based on the same pitch, a characteristic that gives each of these ensembles a unique sound. In any case, the tuning doesn't become stable for about twenty years.

With the Venda people of South Africa, the fourteen note kalimba mbira will be tuned differently by each performer, depending on personal taste, feeling, technique, and competence (since everyone is expected to play music). The pieces, however, are always recognisable, belonging as they do to a common social event. The fact that the pitches of a traditional piece can be variable, not to say wildly unstable, is considered a positive attribute, enriching the tradition.

Likewise, research of the heike-biwa in the north island of Japan shows a similar personalised and variable instrumental input into a traditional music. The distance between the movable frets on a biwa vary from district to district, from village to village, so a melody known throughout a whole region will sound very different due to the way an instrument is set up. If you add to this the standard biwa techniques of extreme pitch bending (pulling the string laterally behind the fret), we enter a tonal world closely resembling The Uncertainty Principle of twentieth century physics (where the observer, merely by observing, changes the observed.)

HT

I assume you mean that for 'observer' read 'musician.' So what you are suggesting is the absolute opposite of the western paradigm, that great composers write God-given music which represents some kind of perfection which cannot be touched or transformed. This is a fairly recent notion. Certainly in the Baroque tradition notation was often merely a map and 'improvisation' was a synonym for 'improve.' It seems clear now that in the period where composer became God, the expectations for the musician were reduced to that of feudal vassal. The audience in turn no longer had expectations that the performers would take responsibility for how the music proceeded and how variation could be applied to fit the moment.

Even the greatest of our classical virtuosos bemoan their total lack of ability to approach this basic tool of music. To their credit, most only try in their studio. To the ears of an improvising musician, the painful attempts at crossover by Yehudi Menuhin, Nigel Kennedy, and Vanessa Mae are embarrassing to say the least.

We are aware of these difficulties and connections between improvising traditions and the classical repertoire now. But thirty years ago, how was improvisation, and at its extreme free improvisation, received in Australia?

JR

Most musicians and audiences did not recognize that this had anything to do with music. A lot of this went on in small art galleries and free spaces. I guess the assumption was, if this isn't music, it must be art. Very few musicians who I knew were either making experimental instruments or playing free improvised music--Louis Burdett, Jim Denley, Greg Kingston, and Rik Rue were amongst the few who were. At the same time, I was doing club gigs, Italian band work, country music, commercial session work, film music, ads, even backing John Denver.

HT

That is the bread and butter work of being a professional musician, but it does not explain your obsession with strings.

JR

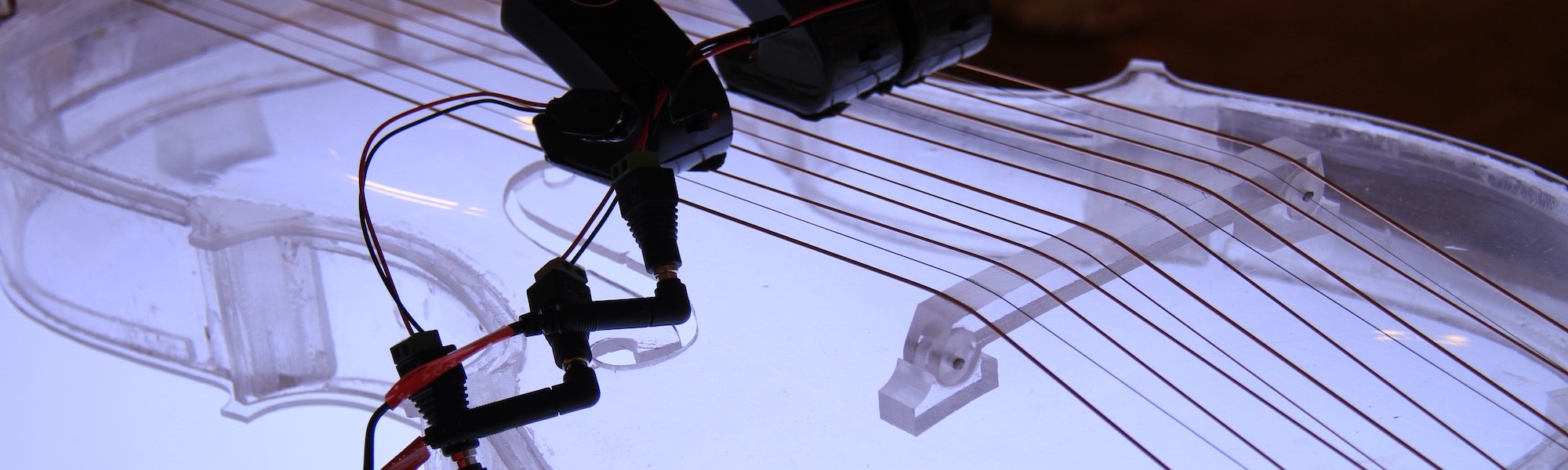

My natural curiousity through playing the violin led me to wonder what happens if the string gets very, very short or very, very long. Maybe there is an analogy with the German artist Paul Klee who spoke of drawing as 'taking a line for a walk.' In some ways, that's what I am doing, 'taking a string for a walk.'

In my early years of violin improvisation, I was concerned with manipulating string noise, using the instrument like some kind of analogue synthesizer. I avoided regular pitch by covering the strings into short sections with tape. Preoccupied with rhythmic complexity in the bow and rhythmic independence between the two hands, I wanted a language where the engine of the violin (the bow) could work in counterpoint with the pitch shifter (the left hand). It was hard-core, extreme. Then, I realised that I could create instruments that would accommodate this stuff much better than the violin. After that realisation, I decided to play the regular violin in a fairly straightforward manner, allowing it to do what it is good at.

I'm interested in intonation, multiphonics, big tone production. It's hard enough just keeping regular violin chops together without all the other stuff. You, too, have developed a unique approach to bowing, getting it to swing and move across the beat.

HT

I made an about-face from classical music to Texas fiddling, bluegrass, western swing, and country music. What I do with my bow depends on what music we are talking about. Of course I spent hours transcribing those who came before me, studying their bowings and accents and every detail of their phrasing. My own style has me constantly speeding my bow up and slowing it down, often suddenly, pushing and pulling against the beat. I try to take this as far as it will go while remaining within the group perception of where the beat is. This is how I underline and project certain notes and rhythms. In any case, I think it should be learned on the bandstand and not in a university. I stood on many a bandstand in isolated towns with dancers looking up at me, awaiting a beat, a feel, that would inspire them to dance. One night sticks out in my memory, when I watched a bunch of dancers walk off the floor once as we started a tune. I had to dig deep and figure out how to get them back on their feet. This kind of music is so related to dance that if you have not played for dancers, you cannot really have the proper feel. Of course, the rock approach is to just hire a loud bassist and drummer, but even without them, there is still a way to reach people. My place, the American West, with its remnants of square dancers, swing dancers, country dancers, contra dancers--this patchwork of dancers is always in my playing.

JR

I think everybody has their own personal rhythm, and this basic rhythm underlines your improvisation, whether you state it or not. I agree that you are never going to learn this in an institution. I remember a solo concert in Hanover in the early 80's where I was playing acoustic violin, and I looked down at the feet of the audience in the front row and they were all tapping their feet, but all in a different tempo. Somehow I was conveying a sense of rhythmic propulsion without giving them a set meter. A personal rhythmic propulsion is something that differentiates the genuine improvising musician from someone who is told by a composer in the score to play alleatorically.

HT

I assume that you can't keep all your projects going at the same time. Do you still play The Relative Violins? If not, do you miss them?

JR

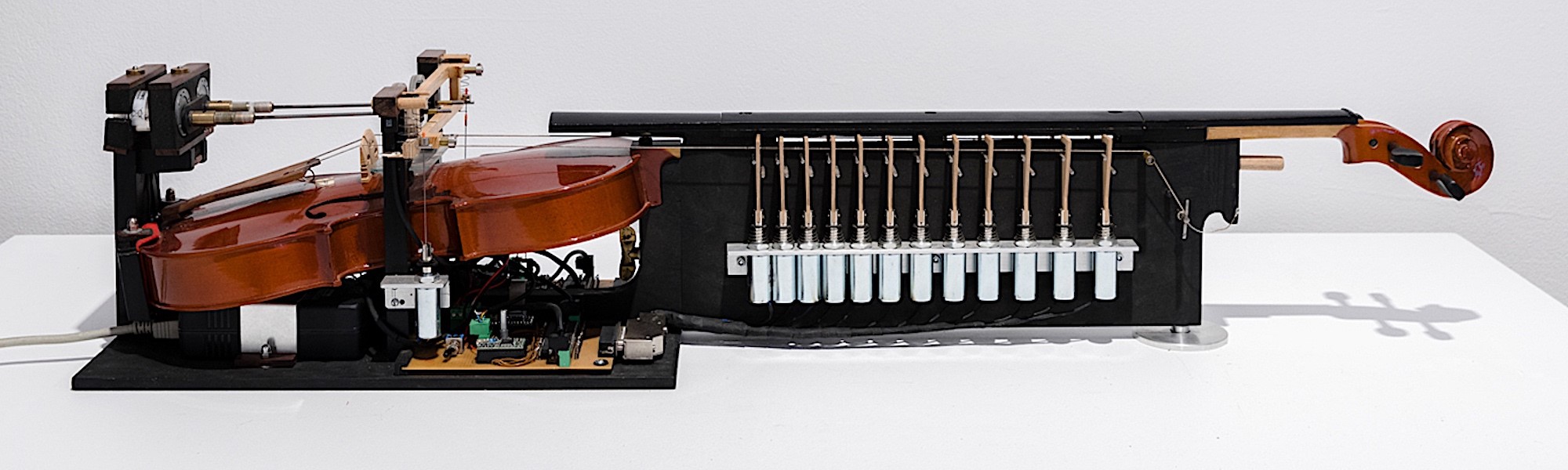

Last year I used the 16-string long neck violin for a recording project while I was on tour in Slovakia. The 19-string cello and the 2-string pedal board have both been used recently in an Amsterdam project with nine other string players. I have an extensive recorded sample collection from many of the instruments which I use in my interactive pieces like 'The Chaotic Violin' and 'The Hyperstring Project.' Everything that I sample I have played myself. It's no substitute for the real experience, but I have some access to that sound world. I have the sense that I can still use the sound but that is not the same as playing them.

HT

You abandoned your homemade instruments for computers?

JR

Not exactly, although instrument making has been on the back burner for the last fifteen years because I have been more focused on interactive systems. I return to them now and again, and when I do there is a completely different angle. I did not make a sudden jump to computers--I had always been building analogue electronics. One had a ring modulator, FM radio, and amplifiers inside, plus outside amps. In the 80's I did some experimentation with a theramin and violin where the movements of the violinist influenced the theramin because of the way its aerial was set up. Signal interference is a major theme in my life. Only a few years later I discovered that I could interface to MIDI. Any voltage with differential could be used to run MIDI, and with that came the whole possibility of movement, physicality triggering and controlling sound. I wanted a system that would respond and contribute to the processes of improvisation.

HT

Do you believe that music can resist commodification, that it has a life beyond a middle-class extension of the leisure and lifestyles industry?

JR

No, as we speak it is being codified and commodified; there's a bunch of people seeking ways to sell it and give it a brand name. They've run out now, trying to find some way to say this is new when it is not. Music can only be the stuff that is made by musicians, by definition. You do meet people who do make music even today, and those people might not even be professional musicians. Is there a future for it--yes. Right now is a bad period because the production of music is being mixed up with the experience of music. Sound is ubiquitous.

HT

Are you disappointed with the twentieth century? Is yours a vision running in opposition to the times? If so, do you create your art in part as a refuge of dissent?

JR

I am not disappointed in that the most unbelievable things have been articulated, discovered, and explored in all fields, not just music, but for other reasons, yes, I am. I would have liked to have been alive in the 20s. Even after the end of the First World War, the first major blast of cynicism, people had a view of 'That's it, now we'll get on with life.' But the Second World War, to have that in the space of one lifetime--I don't think you can recover from that, except by burying your head in the sand, denial, collective amnesia, which I think my father's generation has. To get back on some kind of footing after that--well, we still haven't recovered from it, the Germans are still freaked out, the holocaust industry is on, and that legacy runs through all other kinds of notions of art. Though we are in a new century, it hasn't made any difference apart from the party. I think we're still in the 80's, the Reagan-on-acid, acid being computers. The results are depressing but the ideas remain disturbingly wonderful--Dadaism, for example, probably the most beautiful and wonderful idea of the twentieth century. There were elements of that before, as with most ideas which always exist. It's just how they get expressed, having someone who can isolate them and put them forth. Dadaism is an aspirin for existentialist pain, an aspirin or something more sparkling like Alka-Seltzer.

HT

OK The Relative Violins are to be found at the Rosenberg Museum, on recordings, and also on this web site. What is the goal of the site?

JR

It has a practical side, as in trying to get work, but it's not just self-promotion but ideas and observations and cultural commentary not available in mainstream culture. I'm a cultural protagonist, and the results of that and the information and stimulation possible from that is there for all. I think 99.99% of the population wouldn't care, but there are a few people who can get something out of it. In the makeup of humanity, there are always minorities. If you don't have religion or a workplace, it's comforting to come across someone who is vaguely on the same wavelength.

©Hollis Taylor 2001