Musical Fingerprints in a Digital World

hollis taylor

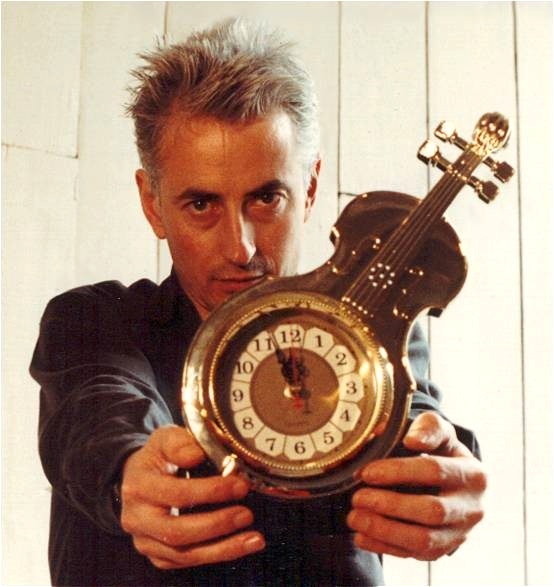

More than a musician, he is an explorer, Austria's Az Tagblatt says of Jon Rose, ranking him in that activity in "a position next to Columbus." Other reviewers compare him to a modern-day Paganini, "conjuring up endless possibilities at the end of his bow," "perhaps taking the violin into the next century," "[a] postmodern Paganini with digital words at his fingertips." The New York Times speaks of his styles as running "from accelerated, tonally centered solos to free-form sonic explorations." Jon Rose, avant-garde musician and composer. "[H]is cello is all corners and ends, spanned by strings everything on board functions. With this he brings all connections to the foreground room ambience, the reaction of the public, satire, personal mood sliding together with unbounded intelligence."

He is controversial. Says The Wire: "Few experimental composers or improvisers divide opinion as sharply as Jon Rose. He is maybe an erratic talent but when he hits the mark he takes you to places other composers wouldn't dream of." Or as El Pais puts it "Jon Rose is more than simply a curiosity, he molests our sense of profundity." From any perspective and whatever culture Australian, Chinese, American, European - Jon Rose is one of the leading figures in avant-garde music, a violinist whose experiments both with deconstructing and electronically reconstructing instruments put him in the vanguard of integrating contemporary electronic and computer technology into the composition and performance of music.

’Chaos’ is the other word that comes up in discussions of Jon Rose’s work. Hurtling in performance into the farthest frontiers of counterpoint, Rose’s various devices enable him to produce sound by the wave of a bow or simply by moving his body. With bow amplification and a vast array of sampled sounds, his violin is less an instrument to be played than a lens for viewing chaos, The Oregonian writes of him. "Master of Chaos" Berlin's Tageszeitung calls him. "The Chaotic Violin" is the name of one of his compositions.

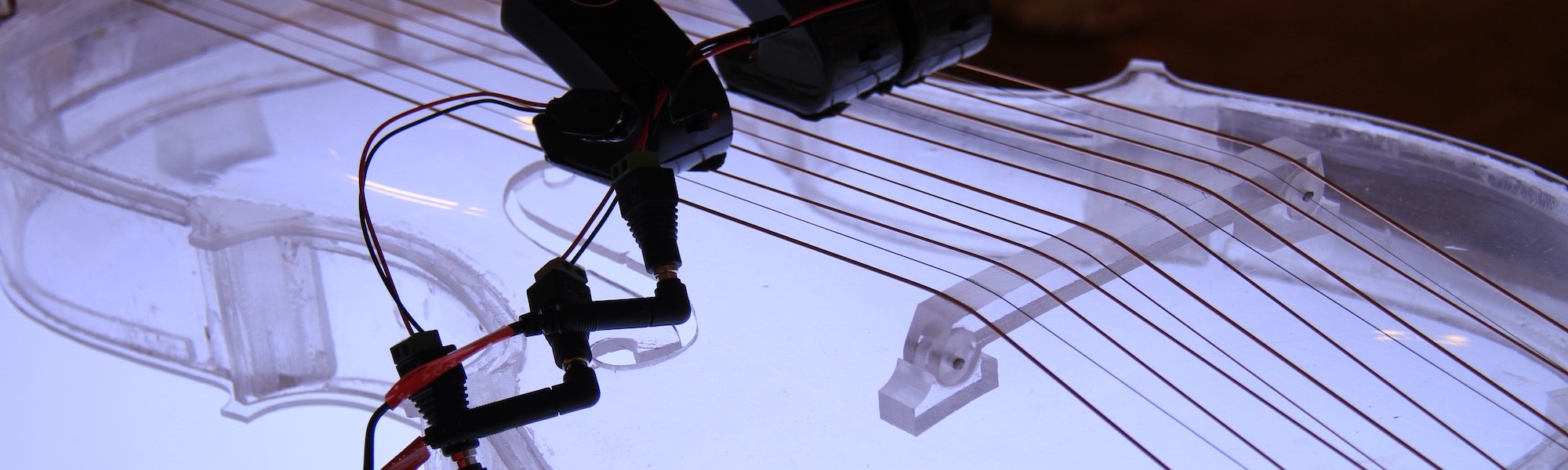

Jon Rose sits in his expansive Berlin loft space, where six violins of his re-making hang behind him, above the grand piano, violins of anomalous hues and even shapes, one with a sitar-like neck, another with double necks sharing a violin body, and two violin bodies sharing a neck, Siamese twins of a sort. Another room is strewn with violin memorabilia and instrument parts, a kind of string instrument hospital. What initially appear to be violins in various stages of repair, or disrepair, or severe undiagnosed trauma, in time reveal themselves as simply part of a working instrument library of a performer become tinkerer/philosopher, and one not limited to acoustic instruments.

"The violin is a powerful icon," he begins. "If you stick it next to anything, there's a commentary there. I take the violin as the commentator, or as the protagonist, into situations where it hasn't necessarily been before, where the violin hasn't achieved the things that interest me."

He likes any possible sound that could emit from a violin, from the cheapest, most terrible sort of scratching to a very standard sophisticated tone. He spends much of his time making and re-making his own string instruments, pushing the limits of musical instrument technology. When he could no longer house his immense and expanding collection of violins and violin memorabilia, he founded a museum in the Slovakian town of Violin.

Jon Rose began playing the violin at age seven. By the 197O's, first in his native England and then Australia, he performed and composed in numerous genres, becoming in the process the central figure in the development of free improvisation, performing either solo or with an international pool of improvising musicians called "The Relative Band". In 1986, he moved to Berlin to continue his work on The Relative Violin, a project that he describes as "a total art form based around the one instrument."

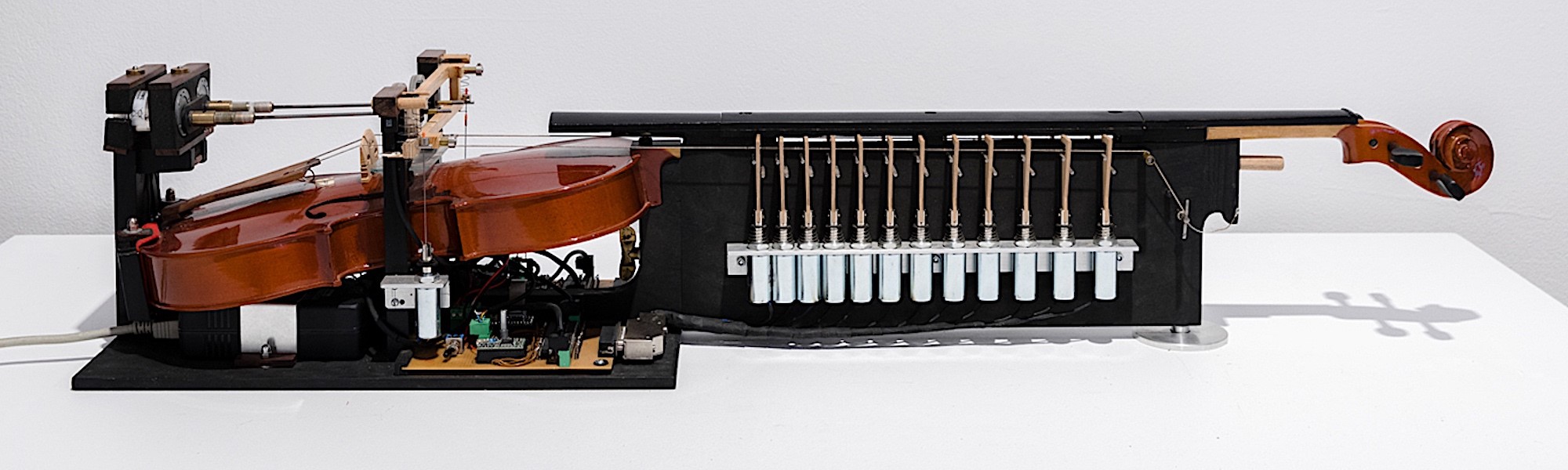

"What's been done so far with the violin and computers hasn't interested me," he says. "But that's why it's important for me to take the violin to the computer, to go in there, and if you like, comment on it, or investigate it, using the violin as a sort of Geiger counter." In 1999, on his American tour, Rose performed his composition, The Hyperstring Project, designed to impel musical expression through the use of MIDI--Musical Instrument Digital Interface, the language spoken by computers and electronic musical instruments--controllers measuring the physicality of high speed improvisation. Its performance requires three primary controllers: a sensor mounted on the violin bow which measures the bow pressure; an accelerometer mounted on the bowing arm, measuring bowing arm movement and, more importantly, speed of movement; and foot pedals which are played independently by both feet, normally playing bass lines and/or rhythmic material. In addition to his innovation in deconstructed violin instruments, Rose is also involved with the development of new instrumental techniques, analogue and interactive digital electronics, experimental radio, writing on contemporary culture, video and environmental performance. When he isn't touring the world (over fifty performances per year) or recording (over fifty CDs), Jon Rose divides his time between Australia, Amsterdam, and here, back in his Berlin loft.

We begin with the real.

HT: When I first began to play my MIDI violin in the mid-1980s, I found that making a sound other than that of a violin, on which I had years of training and a long list of 'shoulds', was musically freeing. I reveled in the ability to sound like a steel drum or a brass choir or to play walking bass-lines while the guitarist soloed. I was listening in a different way and taking more chances as an improviser. But you have taken the process a step further, and not an obvious step at all, designing your own MIDI bow. Why?

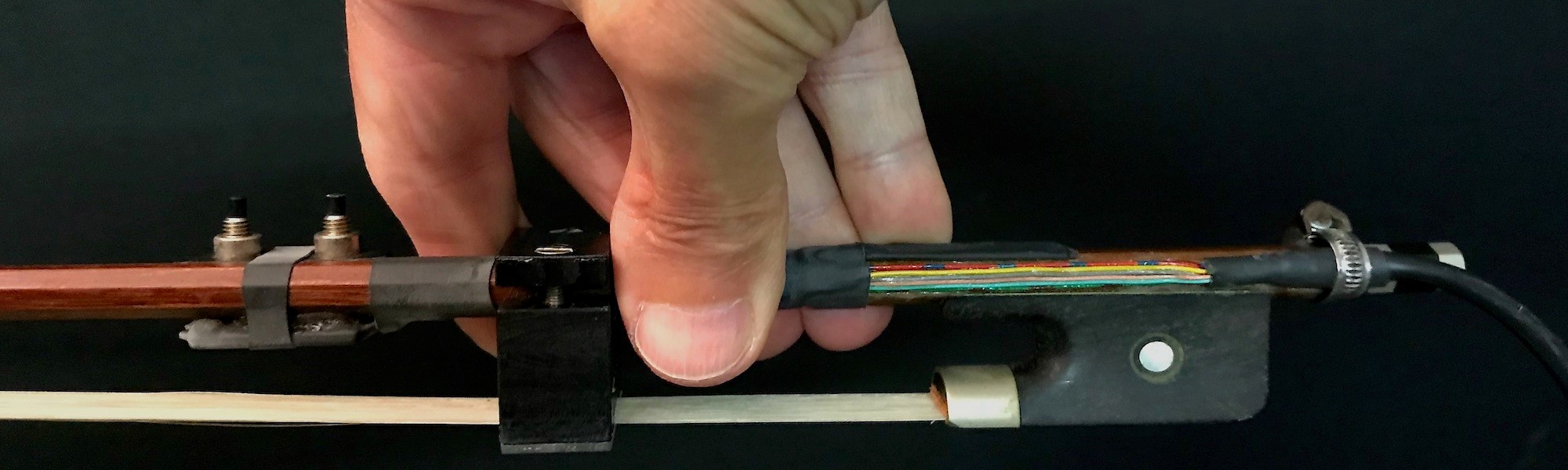

JR: I'm really only interested in digital technology as an improviser, so I'm interested in things that have their own independence and will come back and hit you in the face. Your MIDI violin, in this sense, is the least interesting thing anyone has yet come up with in terms of electronics. I think they even boast how the bridge ignores any kind of lateral bowing, which is like its like having to play in a straight jacket. Beyond that, it's a parrot, and that doesn't interest me at all: You go boink and it goes boink, and something else goes . . . boink. The system I use has 29,000 commands. There's no way it can come back the same way because it depends on how tight you tighten the bow in the first place, the weather, what you played, how the bow is springing back. It's an organic thing, the bow, so if you've just dug into your last note, the hair is slowly trying to breathe out again, and that changes everything: how it reacts to the next thing, which part of the bow you're using, all those things. It's like playing with an improviser who's very good and can have off days too, or have really great days when you just can't deal with him. I program the whole thing, so I am in a way acting as a composer. But within that, the level of decisions and the amount of decisions and the flexibilities are amazing.

HT: Is this the only bow you use when performing?

JR: I use it mainly for solo concerts. Before the bow was developed I used an ultrasound system which was either attached to the bow or the arm, and that measured the movement. It sends ultrasound to a receiver, and a signal comes back, and how long it takes to arrive gives you information, and that's transformed into MIDI information. But it's basically measuring what you're doing, so it's another way of controlling, another way of linking digital technology, which in itself is basically dead and boring, with the business of playing, which is bloody and messy, . . . and sweaty. And for me, I'm not interested in being an electronic music composer, but I am interested in taking the violin into other territories. That's what counts. As I move around the stage, the ultrasound is measuring things all the time, so it is very, very theatrical. It is like waving a magic wand.

HT: Is this ultrasound system as dependable as the newer MIDI bow?

JR: It has about the same degree of dependability, which means there are times when it does not work, of course. There have been moments when it has crashed. It's still a prototype. You can't go into a shop and buy this thing. I've worked on it in conjunction with Steim Studios in Amsterdam. The thing about it is the theater somehow seems eventually to be the connection between these two independent forms at work on the stage, whereas with the bow--you're tied to it. It's like a psycho-drama with physicality. It's the engine that drives the violin, and it's the engine that's driving this other thing, and they're talking to each other. So, there are these systems going on at the same time, and as with all improvising, the best bits are often when there are two independent things, and there's something else going on and you can't say what it is, but there's something there that's connecting it. For me, the bow, with bow pressure, was a much more interesting interface than the ultrasound, which was more movement and theater. Free improvisation has always been the main raison d'être and the main system which I want to use for music. There are other things that I do, like the fictional histories and the radio work, for which improvisation is not so useful. You can use it, but you start to make little stories, and you become more of a composer. But in terms of performing, there has to be a satisfaction, a fulfillment with the physicality of playing. Otherwise, it's of no interest. With the MIDI bow, it's really brought that back, so now I'm playing quite long solo concerts again, which I hadn't done for awhile. There was a period in the early eighties when I was doing very long acoustic concerts as a kind of test, in a way, the longest twelve hours, non-stop. The idea was that the bow could not leave the strings, and you had to really play, too. So I did. I did a whole set: ten hours, eight hours, six hours, three hours. It was quite good technically. I changed position a lot. I played laying down and sitting and standing.

HT: All of that is extremely physical. But you are equally involved with technology in music, which would seem the opposite end of things.

JR: Don't forget that my ultimate project is to make a history about the violin, which means that my range has got to be pretty wide. Yes, I'm involved with technology. But there always has to be a reason behind it, a logic. There's always a reason why things happen, and often the most beautiful and surreal juxtapositions are when you apply some very basic logic to something for which it was not designed. For example, the wheeling violin I designed--the logic that you could measure music in distance instead of in hours. You could have a piece that runs for one kilometer. Why not? The idea of going backward for retrograde. Basically, you're getting an arpeggio. That's why I like sport, the relationship to sport. They are similar activities. You start somewhere, and you don't go anywhere. You do something and it's gone. You could not have done it. You'd still be in the same position, wouldn't you? That appeals to me.

Having begun with the real, the time comes to move on. "What about virtual reality?" I ask him.

JR: I am definitely not doing virtual reality as in toys. New ideas are required for this new technology and to date they don't exist. Right now, the technology is just used to perpetuate basic Hollywood myths or whatever, but fundamentally there's no new idea. Having said that, radio was probably the first virtual reality, in the sense that you could be anywhere and do anything using the clues inherent in the sonic world. So playing God at budget prices has its benefits, especially when you can make, write, and compose most of it yourself. Also, the quality is much better than any virtual reality game and, being radio, the images are really happening. For me, there's no point unless you're doing something which is absolutely a fundamental part of the new music, in the same way that the Bach unaccompanied violin sonatas have to do absolutely with the state of violin playing, the technique, the music, the language, the culture, the society--everything is encapsulated in those works. If you start using modern technology, there has to be a good reason why--a musical reason.

My aesthetic in purely musical terms is the idea of counterpoint. This is the one invention of Western music that is truly incredible, and counterpoint is the fundamental business of improvisers, too. For me, this new technology is getting into another relationship with counterpoint, one which was not possible before. When you're playing on stage, there are bizarre things going on, and I couldn't tell you what is happening, even though I programmed it. The audience certainly can't. I think in terms of pure musical phenomenon. That, for me, is the cutting edge. The one thing that's for sure, about the only thing that's for sure, is that there will be computers.

I saw Jon Rose's The Hyperstring Project performance and found 'hyper' an apt prefix. He was hyperkinetic, hyperfast, a one-man band in a blur of motion and commotion, a hyperactive clown with dead-serious intentions. Hyperstring brings together some thirty years of Rose's experimentation with legitimate, historical, modern, and deconstructed string instruments, 'The Relative Violin' he speaks about. These instruments exist in any performance as real instruments (such as the tenor violin), modified instruments (various amplified violin bows), virtual instruments (samples from a whole range of bowed, plucked, scraped, blown, etc., homemade string instruments), and generated wave forms and acoustic phenomena based on strings. This project tries to extend the usual paradigm of live electronic music which is normally concerned with expanding (padding out the same sound), extending (the ubiquitous minimalist loop), or intensifying (effects such as digital delay), in Rose's words, "what in essence are usually simple one-line ideas, not to say simplistic." By contrast, Hyperstring creates a volatile musical environment where the inherent subconscious intelligence of physical actions determines contrapuntal sonic events. The counterpoint of the violinist's body, arms, feet and finger movements are fundamental to the language and expression of the music. Counterpoint is a form of music which takes full advantage of the human brain's unique ability to identify and follow layer upon layer of sound, and Hyperstring confirms Rose's identification of it as his motivating aesthetic. I asked him to elaborate on the new dynamic of 'rogue counterpoint' found in this work.

JR: Hyperstring can create improvised rogue counterpoint in two, three, or more parts. This is a counterpoint as much between independent physical movements (of the body) and controller devices, as between lines of musical information. The continuous control of any contrapuntal lines, however, still rests with the business of playing the violin, basically a monophonic instrument. There are almost no MIDI sequences used in the Hyperstring software; the MIDI-derived counterpoints operate in real time. When a set of MIDI parameters are switched in, the movements of the bowing arm continually disrupt or interpolate the material (usually pitch and speed). Hyperstring follows a long tradition of polyphonic improvisation in the musics of the world. Particularly inspirational to this project are the one-man band pioneers of the late nineteenth-century street music culture, and music hall 'novelties'; the Balinese Gamelan; the group improvisation of early trad jazz; and the essential contrapuntal skills of Palestrina, Bach, Schoenberg, etc.

HT: Our brain seeks out patterns and connections. Do you find that the inherent intelligence of the physical makes for inherently intelligible music?

JR: No, but it certainly is a fundamental factor in determining the parameters of musical experience. Imagine what the history of music would have been like if the species had evolved with three or more arms instead of two? I guess that's why I've always been attracted to the idea of the one-man band and how far you can take it.

HT: How does muscle memory come into play in your improvisation, and do you ever say 'no' to it?

JR: The memory or intelligence of muscles, fingers, sinews, etc. is a huge part of most improvisation. It's what I call 'physicality' in music. It's the stuff that all improvisers share and can immediately sense in each other's playing, and the stuff that most composers, laptop types, and sound artists don't have a clue about. It's blindingly obvious to an improviser that a computer by itself is not a musical instrument. There is no physiological feedback, there is no idio-kinetic parameter to the playing. The computer is dumb and plastic. That's why I've gone to so much effort to search out ways of bringing this physicality to interactive software in the form of interfaces like ultrasound, accelerometers and pressure sensors. Improvisation takes place on many levels of consciousness. At its best I would say that when you are in a state of improvising, the control part of the brain is just sitting back there and watching the whole thing going on at incredible speeds of decision making. If you had to think out each of those decisions about what the fingers were doing, when and how on such a micro time level (why is not a useful question!), you'd never get past the first note, sound or gesture. If you like, the intelligence has to operate independently within the fingers, within the body. So how do you get this intelligence? You can't get it at the store, and it's not in the manual. There is no shopping short cut to this. It takes hours, days, years and your whole life to develop your little universe. You might call it a personal language. Others call it a bunch of clichés, which in an unoriginal, non-challenging, non-risk-taking person could be true. But this body of reflexes, this personal language, is a transport that can take you (given other parameters like playing with responsive musicians, a good audience, and other stimulations) into the new situation of every single performance. The physicality of response to a given moment in a concert can have you suddenly facing in another direction altogether--change of bowing, making a counter-statement, screwing up your intonation, stopping dead in your tracks, etc., which might not be very comfortable. Like everything to do with improvisation, if you say what it is, there will come along a situation that will redefine that. Improvisation resists analysis. Apart from the most enjoyable experiences, which are normally about playing with other musicians, I enjoy the challenge of playing in situations which discount that option, like the marathon, non-stop solo-violin solos I used to play or playing in situations completely out of my control when the music is being conducted by the speed and frequency of traffic flow at a street junction. In these kind of situations, it is often the gestalt, it is the tension and juxtaposition between two diametrically-opposed systems that causes combustion. Do I ever say 'No' to the memory? I have been in an improvisation where I seemed to have reacted on a level which is saying "No, I don't want that again." But normally I would be aware of it after the actual event. The moment has already gone. Saying 'Yes' or 'No', the decision-making process, brings a whole other side to music and computers. Whenever you work out a piece with interactive technology and let the computers, rather than the musician, have random access to the decision making, in my experience, you are asking for an extremely reductive and boring result. I built an interactive badminton game (modeling the Jekyll and Hyde brain of the brilliant composer, pervert and sadly racist Percy Grainger). The rackets triggered a whole lot of sound and images; movements of the rackets modified the material. But the program didn't see it when the players dropped or broke their rackets, or tripped over the cables, scratched their arses, or when someone in the audience yelled out something. We can suddenly transform our perspective of the moment to include all kinds of lateral thinking way beyond a computer. We can do these contextual.

HT: How do you feel when you are in the midst of playing with all the computer interaction?

JR: I was on tour in Japan with trumpet player Toshinori Kondo, and we were relaxing in a bar when this big burly American professional tennis player came over and started to talk at us. Kondo gave me a look - "Boring", we thought. But after a few drinks he started describing the business of playing doubles at the international level. He said that the player had to see or be aware of the whole court as a three-dimensional space, from the outside, while involved in the playing. If you just waited to hit the ball, you would be too late. This seemed one way of looking at improvisation and is really pertinent to playing in the middle of interactive systems. When all the equipment is working okay, then I feel very clear, quiet in my head, I notice things from a distance, although the music might be very busy with four lines of counterpoint running (that's one real improvised violin line and three interactive lines). If something goes wrong or my attention is disrupted by something (a member of the audience throwing a beer bottle at me, for example), then I seem to surface to another sort of reality altogether. On specific feelings to do with the touch of the different interfaces, the bow is probably the most problematic in the sense of its duality of purpose. On one level, it drives the violin. Then, with the same information (pressure), the bow is simultaneously driving an interactive system. This information causes independent lines to function. This is real time MIDI, I'm not setting off sequences that take care of themselves. If there is no pressure information, then there is no sound. These lines can be as complicated or simple as I chose to make them, they can be pseudo-random (there is no such thing as random in computers as you always have to set parameters at some stage); selected notes, as in a tonal scale but not in any particular order; a linear, exponential, or logarithmic wave form between two points; or one note if you want to cop out. There are other parameters dealing with the speed of change and the way the MIDI information is accessed. The accelerometer is dealing with the movement of the bowing arm in a similar way, although as I have it set up at the moment, there are a few sequential slots. In these the movements of the arm cause interference to the sequence using an alternative set of random notes, so the two note systems are interpolating as my bowing arm moves. Also, with an accelerometer you get two kinds of information for the price of one. There is the basic linear information if you move your arm through 90% and there is a sudden surge of data if you move your arm suddenly. It feels a bit like throwing a bucket of MIDI information at the wall with a resulting mass of sound. I also have MIDI (note on) pedals. I first thought of having s omething like an organ pedal board (this was directly inspired by a certain Nicholas Bruhns (1665-97), town organist of Husum, who became famous for improvising on the violin while adding a bass part from the pedal board of the church organ). But then I realized the practical horrors of carting this junk around the globe and realized that just three small pedal switches would be enough, one pedal for each foot and one pedal to change the function of the other two foot pedals. These operate quite simply and trigger samples. Some of the samples are quite long, so they give the impression of the content being sequential. Rhythmically stomping up and down on these pedals is very physical and exhilarating, something that would not go over much at the violin academy.

HT: How much does one performance vary from another?

JR: Limited amounts of sample space, limitation of RAM, unreliability of a PowerBook (I won't use one on stage) mean that I am dealing with an interactive system that is far from what I ideally want. But being an improviser means that I am always dealing with the imperfect situation. Music is the transitory and impermanent expression of the failed human being. I could set the whole decision-making process (via MIDI program change commands) to random select, also all the notes on information, which would mean that every concert would by definition be different. But, as with improvising on an instrument, it is the combination of familiar usage with radical surprise that generates a useful and versatile language. However, I'm constantly changing the sounds and tinkering with the software (with a lot of help from the software engineers at Steim--I am too old [Rose was born in 1951] to have been brought up as a cyber-nerd). With regard to the violin, that's what changes the most from performance to performance, of course. I couldn't repeat a violin performance even if I wanted to. (A joke I have with one of the software guys at Steim is that if I had a violin that crashed as much in one day as his Macintosh, I'd put it on the bonfire). To analyze what goes on with the bow on the transient of each of the tens of thousands of notes that I play each concert would keep a research scientist in work for life. Those subtle shifts of weight, speed, position, intensity, touch are extraordinary if not metaphysical. You can't get anywhere close to that with computer-based note production. Even with a different sample for each of the notes used on a violin, we are still nowhere; even with ten different sampled notes for each on a violin, we are still nowhere. Even with changing the envelopes [the actual shapes of parameters in sound] with two different LFO's [Low Frequency Oscillator], thus making the note sound different each time, it comes back; we are still nowhere compared to the subtlety heard from a good violin player (or even a bad one).

HT: Has technology undercut the status of the acoustic violin, the violinist, the human?

JR: The music industry today is only about status and the marketing of that status. Everything else is irrelevant. The better, the faster, the more far-reaching the technology means the better the marketing and the higher the status. Yawn.

HT: So, are you suggesting that technology has undercut music as a transforming experience? All technology? Since you yourself are a user, where is the dividing line?

JR: I'm just coming from a concert that I gave at a small club in Poland--one of those exceptional nights when you never seem to run out of ideas and feel that you can just keep on playing and playing. In fact, I was so 'transformed' that I didn't see the edge of the stage, and fell quite badly, but I can honestly say that it felt that we reached moments of first-hand experience that defied the rationality of mathematics, even though I was using an interactive computer system. As with the best of improvisation, we seemed to be existing at times in a story that was more than the logical sum of its parts. Not every night is like that, of course; sometimes it's just hard work. Music seems to me to be as basic as sex and almost as old. It satisfies a basic purpose, a shared sense of existence. It has no meaning (except in a dumb sense of "this is a minor chord so it means sad, this is a major chord so it means happy"), but the playing of music satisfies a need. You have to do it because you have to do it. The use of music as a marketing tool for cigars (Bach), ice cream (Handel), etc., (make your own list) is so the identified shopper can strike the appropriate emotional, pseudo-sophisticated pose. It has no meaning, anymore than any symbol actually has meaning. In the complexities of improvisation, recognition of beauty or order does not mean that you have to explain it. It's no coincidence that the decline of live music performance exists simultaneously with the mind-numbing Muzak [canned music, e.g. as in elevators or telephone 'on hold'] that emanates from just about every orifice in public spaces. We are living surrounded by Muzak. What was once a musical experience has been reduced to an electronic Muzak drone. I've heard Thelonius Monk in supermarkets--it doesn't get much more perverse than that. I'm often in a public space, and I hear Muzak and I think: Someone voluntarily put that on. No one put a gun to his head and said, "You must help liquefy the brains of all who will hear this." It was done voluntarily. Does humanity have a suicide wish? Remember that the entrepreneurial John Cage copyrighted and marketed silence way back in 1952; he knew it was a vanishing commodity. I'm surprised that 'silence' isn't up there as a big investment on the stock exchange, along with all the start up e-companies that don't make anything. There is no escaping it because all rebellion against the status quo eventually becomes product (sometimes only a few seconds later).

HT: I wonder if Muzak 'musicians' and garage bands and laptop musicians could accomplish more without this access to technology. I would guess they are simply not destined to be great composers. Aren't most of us just hosts for ideas that get replicated, although perhaps in modified form, from person to person, hosts for ideas rather than creators of them? Great composers have always been a rarity. Why the concern?

JR: I'm not supporting the view that the only music worth having is western and great. On the contrary, I believe that improvising in all its forms should be considered the world norm, and what happened in European culture (the rise of the autocrat composer, the romance of the genius) to be a bit of an appendage, and the results (when married to the shopping enterprise culture today) quite disastrous. I was talking more about the ease with which it is possible to replicate yourself all over the planet, whether you have any talent or originality. The concern is that we are drowning in a sea of audio, most of which we probably don't need, like the people using mobile phones on trains who insist on telling all the other passengers on the train very loudly that they are "on the train".

HT: Do you think that technology, including the global nervous system that is the Internet, can affect us to such an extent that we will find ourselves with increasingly and irreversibly deadened ears and dulled musical sensibilities? Could the cultural then become the physical?

JR: The whole industry of digital repetition might be dulling our hearing sense. We might be getting more stupid. Repetition on computers is ubiquitous, it's what they do well. But that's also the problem. All this laptop stuff is just the machine regurgitating away. It's easy, requires no energy; no one questions the machine, no one questions the loop, it's on page one of the manual. The other thing that seems to pass the lap top generation by is the whole notion of pitch itself. It's like they are saying, hey, man, pitch is redundant, now there's only noise, texture and a non-stop 4/4 beat. I get the feeling sometimes that people don't hear pitch relationships anymore, hence the massive popularity of the electronic drone. It's sad. Pitch is such a wonder, it's a fundamental of sound. Music-making is being rendered the activity of a bunch of recording engineers at best. I have nothing against recording itself (remember I've made over twenty major experimental radio pieces about the violin). But recording by itself is not an interesting story; it's not even half a story. It's too reductive. Listening by means of the physical experience of playing an instrument is not the same thing as sitting passively in a chair listening to sound coming out of a stereo system, enjoyable as that may be. I've been busy working with computers over the last twelve years to maximize the intelligence of the human body (as in a violin player) and its inherent qualities, not to replace it.

HT: Your mind is implicated, and your music sophisticated; yet you return again and again to the physicality of it all. How much do we miss by not being in your shoes on the interactive pieces?

JR: Listening is so personal. Audience members sometimes remark on an aspect of a concert that I'm not aware of at all. Certainly, no one can be in my shoes, nor I in anyone else's. A consensus of mood can be faked up (everybody say 'yea') at performances like the Nuremberg Rallies or a big rock 'n roll concert or The Love Parade (a dance/party festival every summer in Berlin where two million tourists turn up). It's not a problem I will ever have to deal with. A hundred thousand years ago in the Savannah, we had to have an extremely well-developed physical intelligence just to survive from day today, to perform the regular tasks like hunting with a bow, then being able to play music with a bow. We are letting ourselves be turned into unemployed vegetables, a species with no functionality and delusions of freedom. Computers are making us stupid. There are some amazing examples of memory by famous Persian singers from the last millennium (all women incidentally). I came across them in Al-Isfahari (The Great Book of Songs), which was compiled in 976 AD--some twenty-one volumes and over 2,000,000 words. It records that a singer named Uraib had a repertoire of 21,000 songs; another, Badhl, had an incredible 30,000 hit tunes; but poor old Ziryab could only manage a miserable 10,000 numbers from her memory bank. Even if they were exaggerating their mental prowess, even if a lot of the songs were almost identical, we are talking about the slow death of the aural tradition here. Jazz would be the paradigm of this disaster, as it is now mostly learned at college, from books and play-along CDs, not from a live music tradition where the player learns through the 'playing ears'. The ability to send huge amounts of data whizzing around cyber space is a dangerous and destructive toy in the hands of an adolescent species. I'm talking about data that negate the responsibility of content, of personal investment of your life (time), that negate generating new content, the cut, paste and control of everyone else's experience that negates the deep, personal and irreversible; except soon, there will not be 'everyone else's experience;' it will all be the same experience. There's your global nervous system for you. The laptop generation of 'musician' (I think they seriously believe they are) assumes that the world of music has unlimited potential to be ripped off and plundered--there'll always be more where that came from. Excuse me, but there's not an unlimited supply of extraordinary music (pick your own hyperbole, unique, radical, revolutionary, etc.). En masse, humans are not that smart or that interesting. Unless artists get off their arses and generate new content in their various traditions, the whole notion of a living culture is going to disappear. I was as guilty as anyone when I first used sampling technology. Now, as much as possible, I only sample the sounds of my own home-made instruments, or sounds I have actually created electronically, or I sample unique sonic situations that I have witnessed first hand. This is not a moral position, it has only to do with the replenishment of sonic resources.

HT: Is the sound of a homemade acoustic instrument discernible by the average ear once it has been digitally processed? What sets you apart from the people you criticize for endangering the ear's ability to hear intelligently?

JR: There is probably not too much that is discernible to the modern average ear. If there was, there would be riots in public places with the speakers that convey Muzak ripped out of their sockets. If this sounds elitist, then I will die as one. I'm sure that very few people in any live audience of mine care if my sounds are from my own instruments or bought off the shelf from Woolworth's. But I care--otherwise, I wouldn't bother.

HT: Some futurists predict that as computers become many times more powerful in the decades to come, they will start to resemble life forms. Then, will they be able to take your place as the Hyperstring Project violinist?

JR: And the Internet is going to save the planet, right? This idea is straight out of the religious zealotry upon which the US is built. I understand that in the US now, for $60,000 you can have your body frozen (cryonics) and kept for the time when medical science will be able to bring you back to life. Even if this is possible, what are all these rich frozen vegetables going to do with all that eternity--watch repeats of Baywatch, listen to repeats of the pop music of their youth? I intend to be fully fried, not frozen. What would a computer want to do, having been programmed by a human being or even another computer? The same old boring stuff, of course. These kinds of leaps in imagination are beyond our constructs. As someone wrote on the wall at Steim Studios, "If the human brain were simple enough that we could understand it, then we would be so simple that we couldn't." However much we learn about the brain, there will always be another level of incomprehension to deal with. There is still no actual theory of cognition. I think that recognition of mystery is the most significant part of the human condition. Very few people can put up with that, hence religion. The paintings in the caves at Lascaux in France and elsewhere show that the human brain 30,000 years ago is the same brain as we have today (except the contemporary one is slightly smaller). Those are modern and highly skilled works of art in those caves. The artists dealt with the same mysteries as we have today. In essence, we remain the same. I don't see us fundamentally changing, although new drugs may make us able to improve out fading memories, we could live longer, we could maximize our potential much more. But maybe the question is what kind of life form would it be worth a computer trying to resemble? Surely not us, hence no violin music of any kind would be required!

HT: Music is too complex to be processed by any one part of the brain. Even as brain science inches along, we know that acoustic sounds are the easiest for the brain to process, and speaking personally, the ones most likely to leave me standing outside myself. Going back to an earlier time in our history, to a brain that never heard an electronic sound, to a brain that made the Lascaux cave paintings, to take your example--could this brain follow The Hyperstring Project?

JR: That's some question. The conceit would be that he would have no problem dealing with the various uses of a bow. He might well consider (like me?) that the bow has magic qualities, although there is no evidence that the bow and arrow were invented by that time (but plenty of evidence for spears). As for comprehension of musical language, that appears to be only a comparatively recent problem. I tend to believe that 'dumbing down' was not a fashionable option in those days; music then had a clear social value and set of functions, and all those listening shared the same belief system. Music was probably supposed to take you up not down. There is something about playing a violin amidst all the perceived digital complexity, it gives a sense of scale and human struggle, fragility, vulnerability, and of course association of emotional and rational ideas. Everybody knows what a violin is, right? So, with a violin in your hand, you can go hunting in the digital jungle. It gives a little credence in a situation where you need all the credence you can get. I'm not sure that The Hyperstring Project is something to 'follow'; it's more like something you find yourself in the middle of. The idea of physically morphing with the medium might have been quite a common notion 30,000 years ago.

HT: You seem intent on making a musical fingerprint in a digital world despite the inherent contradictions and oppositions at every turn: physical/technological, acoustic/electronic, emotional/rational, home-made/machine-made, artificial intelligence/human intelligence, programmed/improvised, user/critic. Trying to walk an honorable path, or to even seeing one, seems quite daunting.

JR: All this may give you the impression that I am some kind of Luddite dressed up in digital clothes. I am not. I just don't see the necessity for digital technology to destroy acoustic music-making or at least reduce it to some exotic freak show. Technology has always been an inherent part of music (the church organ, the piano, the saxophone, etc.), and it should remain so. Creative and critical use (working around the corners and in the gray areas) of these hypertools can be where it's at, but let's not all voluntarily drown ourselves in a sea of digital porridge.

Hollis Taylor

Centro Galego de Arte Contemporanea, Madrid extract from the book 'Connecting Creations', published in English and Spanish ISBN 84-453-2862-x