Drawing the Line

René van Peer

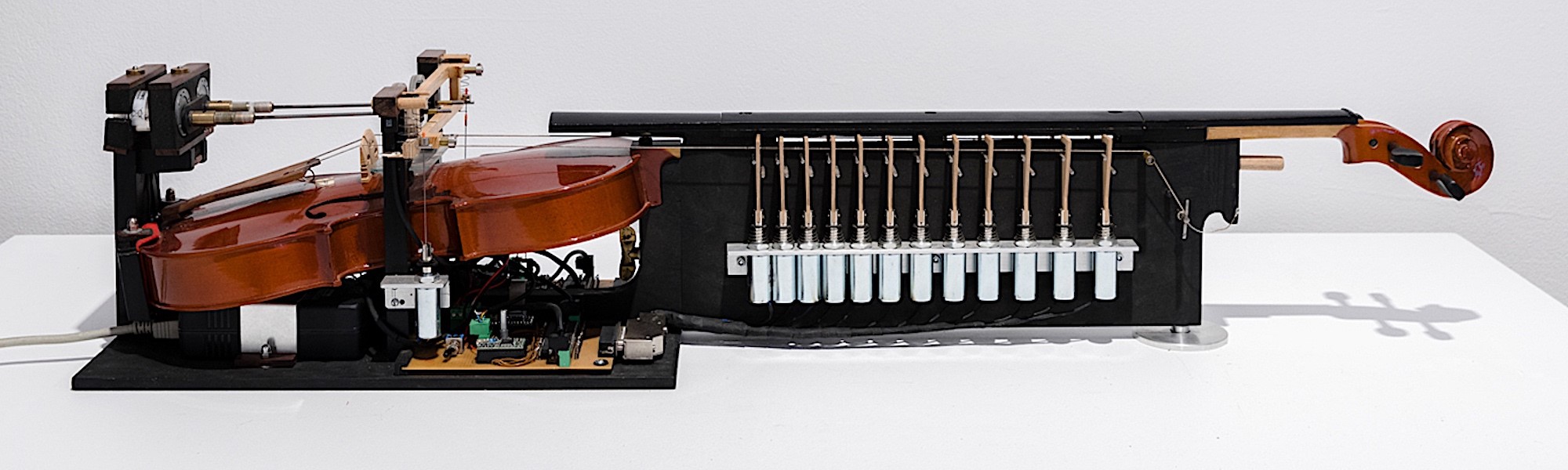

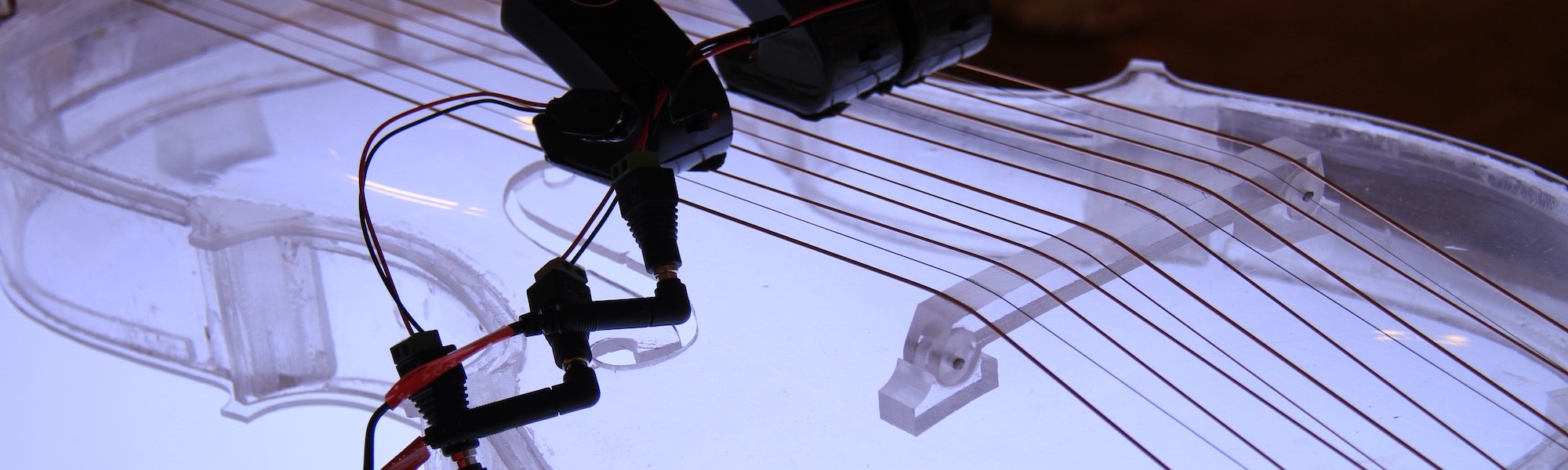

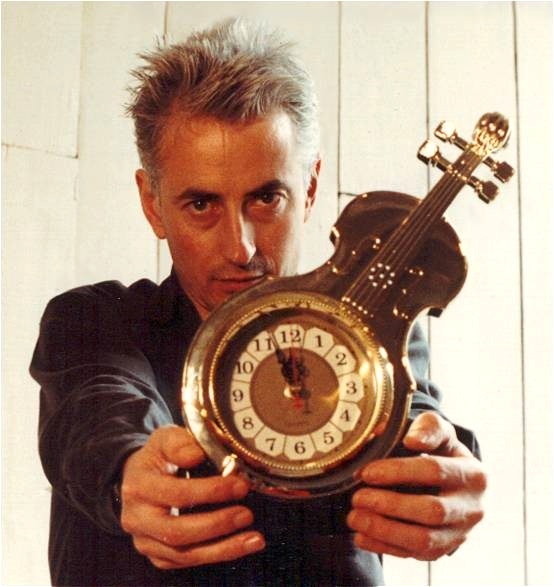

A major achievement of the USA in the 20th century was the victory of the Civil Rights Movement - racial segregation was banned from public life. Finally the basic tenet of the Declaration of Independence, that all men are created equal, had nationwide found its way into legislation and its implementation. A line that had been drawn to separate people, had been erased. Such lines exist everywhere on this world. Violinist Jon Rose ran into one of those when he was in Finland to participate in the 1995 Viitasaari New Music Festival - a barbed wire fence that, marking the border between Russia and Finland, was a remnant of the Iron Curtain. He recreated a model of it for the festival, playing it as a long string instrument. This performance was the starting point for a larger project about fences all over the world. This resulted in a radio play commissioned by the Berlin broadcasting service SFB, and now released on CD.

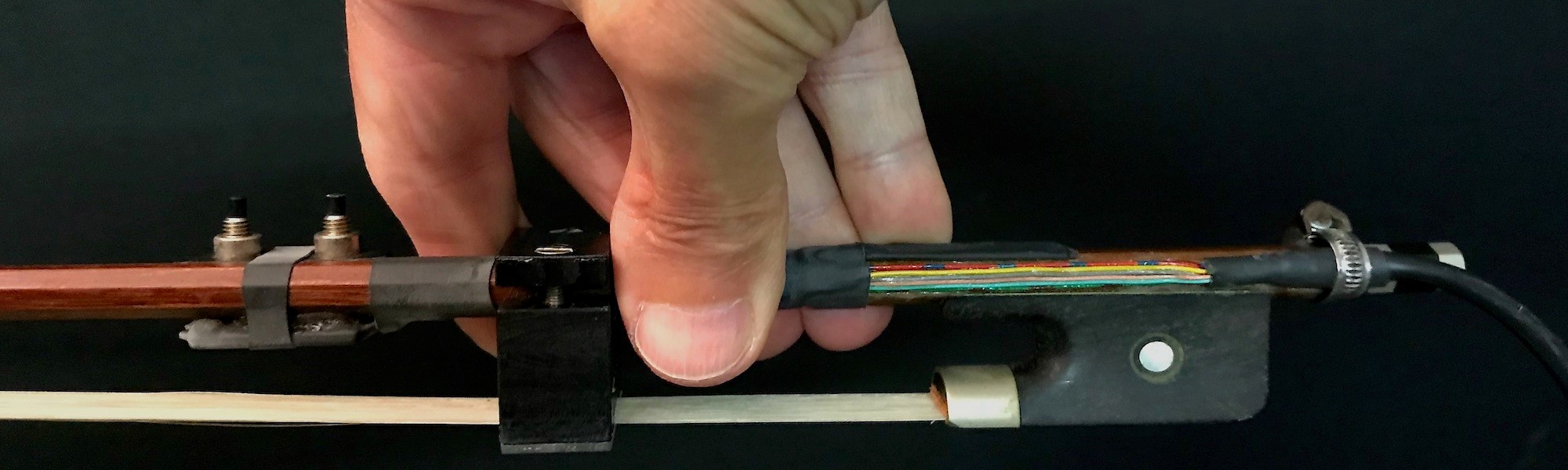

Rose constructed the musical material of the piece mainly from recordings of the long string instrument he built in Finland; one passage is a recording he made of a border fence in the Australian outback that separates desert from emptiness. In some places violin and voice have been added. The sounds coaxed from the long strings are simply magnificent. Bowed, beaten and stroked the strings emit alluring tones, full of shimmering, ringing harmonics. Especially wonderful are the extract recorded in Australia where the strings are played by the wind, and a passage where a voice sensuously curves around the pitch of the string, evoking wildly pulsating difference tones.

Rose constructed the musical material of the piece mainly from recordings of the long string instrument he built in Finland; one passage is a recording he made of a border fence in the Australian outback that separates desert from emptiness. In some places violin and voice have been added. The sounds coaxed from the long strings are simply magnificent. Bowed, beaten and stroked the strings emit alluring tones, full of shimmering, ringing harmonics. Especially wonderful are the extract recorded in Australia where the strings are played by the wind, and a passage where a voice sensuously curves around the pitch of the string, evoking wildly pulsating difference tones.

These sounds provide the setting for ten miniatures portraying fences in different places. The narrative, sometimes based on clips from radio programs reporting on one of these metal dividing lines, consists of studio constructed cameos of the places and voice-over commentary by Rose in German. Starting in Finland he moves to Belfast, the demilitarized zone between the Koreas, Cyprus and several other hotspots, where fences are used to deny people access to a certain territory. He takes the listener on a tour of conflicts stemming from the various differences people may perceive between each other. Ethnic, as in Cyprus and Bosnia-Hercegovina. Religious, as in Northern Ireland. Political, as in Korea. Or particularly potent admixtures of motivational differences, as on the Golan Heights between Israel and Syria.

Most of these conflicts have exacerbating secondary motives - especially strong when they are economical in nature. There is a bitter irony to this, and this is where Rose's satire unfolds in full force. The Berlin Wall, replacing barbed wire fencing in 1961, was breached by people from the eastern part of the city who didn't want their movements to be constrained anymore by their political leaders. After the Wall had been pulled down, the huge serpentine scar of no-man's-land running across the reunified city was to be developed as soon as possible. Not only should the city be prepared for its reinstatement as Germany's capital; looking into the brave new future on yonder side of the millennium divide, it apparently wanted no reminder of recent history to remain. The most coveted part of this immense vacant lot, the Potsdamer Platz, was sold away to corporations who match their bid with the dimensions of the highrises erected there. It is here that the irony kicks in: the new, capitalist, owners have erected fences around their property to protect their building investment. And so, again, the movements of the people are constrained. Now by powers on the other end of the politico-economical spectrum.

These fences are here to stay. Jon Rose likes to point out that, after this recording was made, enmity has flared up in several places he portrayed here. There is more to it than that, however - as dividing lines between people fences are the manifestation of a mentality that is ingrained in our very being. Their being erased from the law has not removed them from individual hearts or minds, or indeed from society. In its setup The Fence is similar to other albums by Jon Rose - it documents a radio play of his, in which his music underpins a narrative that is replete with satire. What makes it stand out is the seriousness of the topic. Although Rose still directs your attention towards the absurdity of the human condition, he goes beyond merely poking fun at human folly. The juxtaposition of the serious and the absurd lights up in the iridescence of the long strings. While Rose makes your ears bask in an alluring lustre, he taunts your ease of mind like a gadfly.

This piece is paired off with Bagni di Dolabella, rather more run-of-the-mill Rose. The ingredients are similar - music (here realtime and sampled violin) with a satirical narrative built on top, consisting of a monologue and evocative sound effects. Based on "an original document found by the Rome City Sewage Department" this radio play for RAI in Italy transports you to Ancient Rome where a masseuse guides you on a tour around the thermal baths, divulging the corruption of a top brass politician. Apparently nothing much has changed since those times. Although Rose's playing is superb as always, The Fence reaches further and deeper as a composition and a narrative. In pieces such as Bagni di Dolabella Rose is merely an observer from the sidelines, amused by the futility of human endeavor. The Fence seems to stem from genuine personal involvement. That makes the bite of its satire hit home. It is as if Rose has discovered something within himself that he is not at ease with. He has looked straight into it, and now offers it to the listener, saying, "And how about you?"

René van Peer

Leonardo Magazine