Wunderkammer 2018

The Rosenberg Museum

By unpopular demand and for the second time in Australia!

Dr Rosenberg's Wunderkammer was curated by Catherine Benz and Jon Rose.

The collection appeared from 10th March to 29th April 2018 at The Delmar Gallery, Sydney

Video extracts taken when the wunderkammer was live are available here. Some of the artefacts on display when the museum was in exhibition mode are available here.

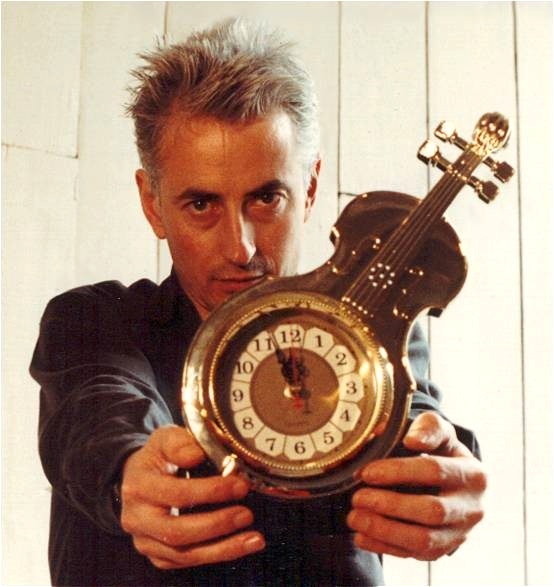

Installations of The Rosenberg Museum have been featured all over Europe in its 30 year life, now it's finally back in Australia and looking for a permanent home - so if you know someone with deep pockets who is into contemporary art, new music, Fluxus, violins... please contact the museum. The museum is the creation of violinist, composer, artist, inventor, writer, Jon Rose and houses a cornucopia of violin iconography - a cabinet of curiosities highlighting violin stories that are musically other, historically twisted, or culturally critical.

Despite being dead for over 20 years, Dr Rosenberg's facebook can be viewed and heard here.

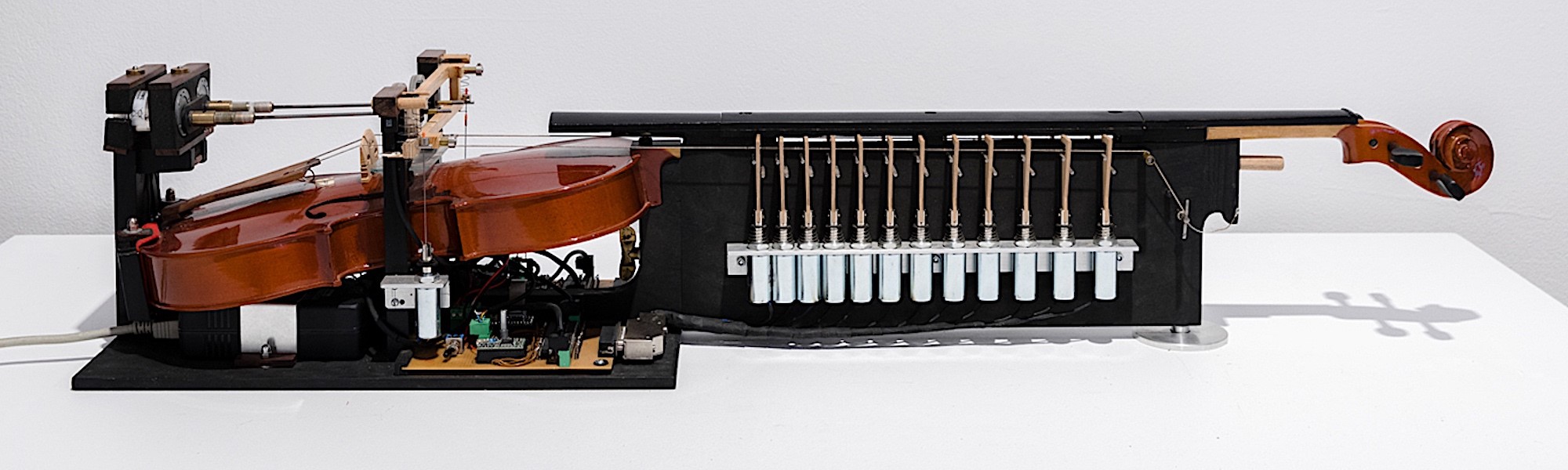

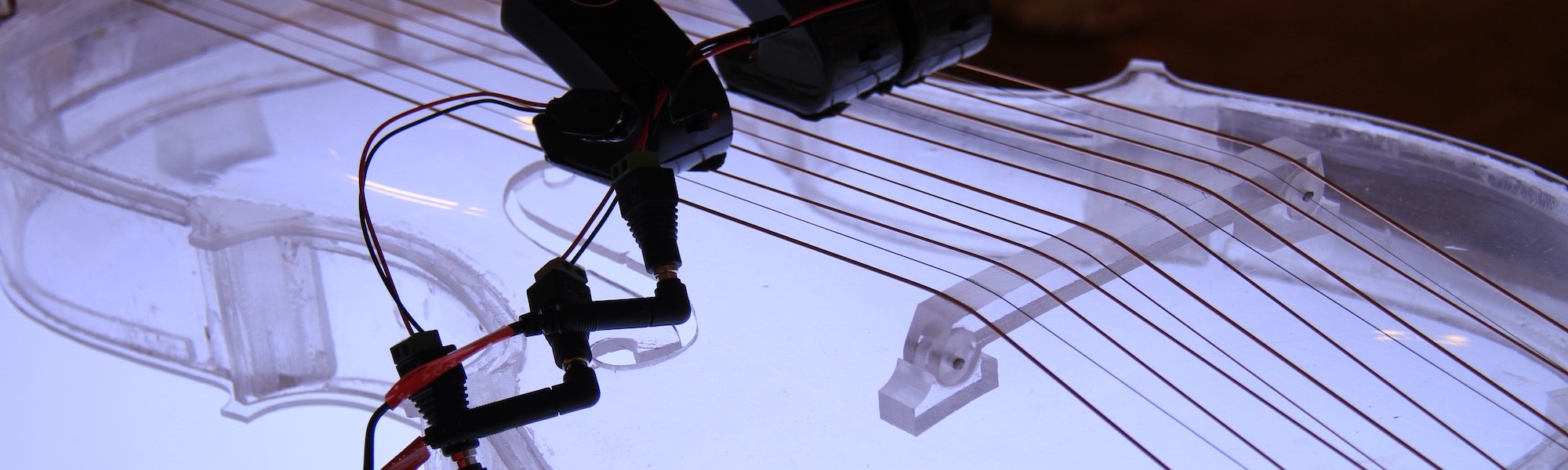

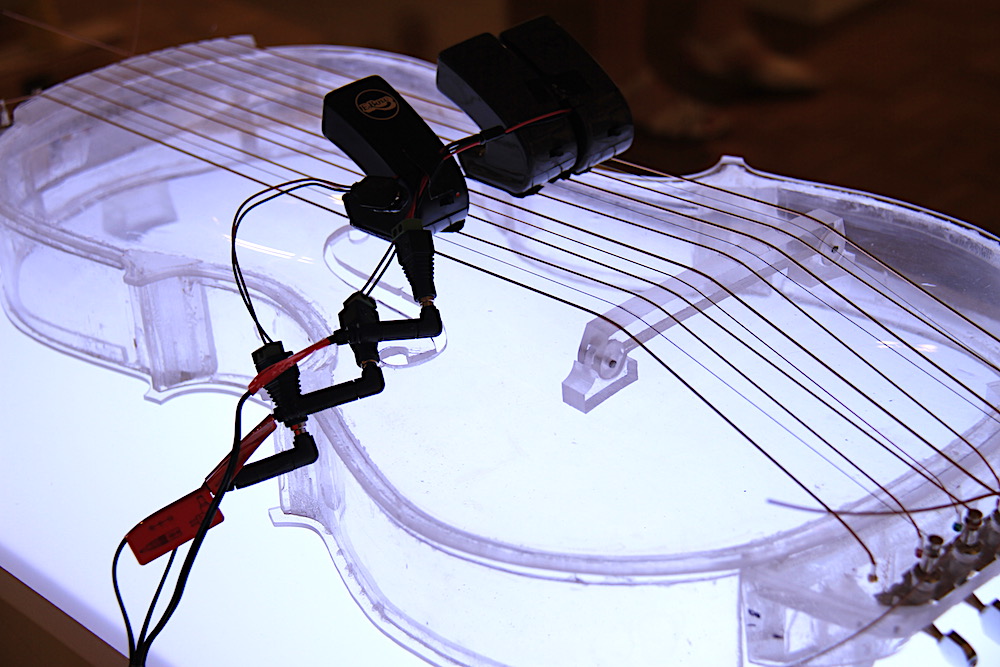

Amongst the collection was featured the new Diaphonium, the One String Horn, the Chair Harp, Ross Manning's RotoViolin, the restored Violin Record Player, a reinforced steel violin case owned by a Gurkhas Battalion in WW2, the ammunition box made in the trenches at the battle of Bannertreu in WW1, a robot violin played live by very wealthy Wall Street traders, a player piano transcription of a Las Vegas casino where extremely poor people lose the rest of their money, violins powered by Robbie Avernaim's SARPS, the ever popular well strung amplified coffin, a plethora of home-made instruments including The Fence, The Plectraphone, The Traveling Monochord, the 6 String Downpipe, the Bowing Wheel, a replica of Paganini's penis, an abandoned electric organ, the ultimate book of music criticism 'rosenberg 3.1 - not violin music', and violin iconography that is profound, humorous, bent, and often transgressively challenging.

Special guest instruments to be heard and on view were The Guitello by Ruben Palmer and the Oil Drum Cello by Danniel Biedermann. Many people have wondered what a piece of amplified strung corrugated iron sounds like when struck with the wind screen wiper of a Holden VR Commodore - now the Rosenberg Museum is able to supply the answer and it is awesome.

Big thank you to the following Musicians who took part in the Wunderkammer:

Ross Manning, Freya Schack-Arnott, Ruben Palma, Noam Yaffe, Mimi Kind, Robbie Avenaim, Jenny Eriksson, Tommie Andersson, Michaela Davies, Erkki Veltheim, Dave Ellis and his double bass orchestra, and Daniel Weltinger and his band.

A visitor to The Wunderkammer asked me why do I continue to make so many musical instruments?

There is empirical logic; a new instrument will produce only new music. There maybe references to other musics played on other instruments by experienced hands and ears, but a new instrument, by definition, is going to generate new sounds previously unavailable. What are the other driving forces to keep doing this? It certainly doesn't help a career in music, it's often impractical and time consuming. There is not much to recommend it beyond the sheer pleasure of the doing. However, no matter how sophisticated the project, there is a moment which comes to all new musical instruments, the point at which a string is attached to a previously un-resonated object. And that moment cannot be replicated. Further on down the track I may find other ways of playing this new instrument, or a re-purpose it altogether. But that initial sonic moment is the magic bit. Sometimes I will cheat and I'm stringing the instrument up before it's really finished - patience please!

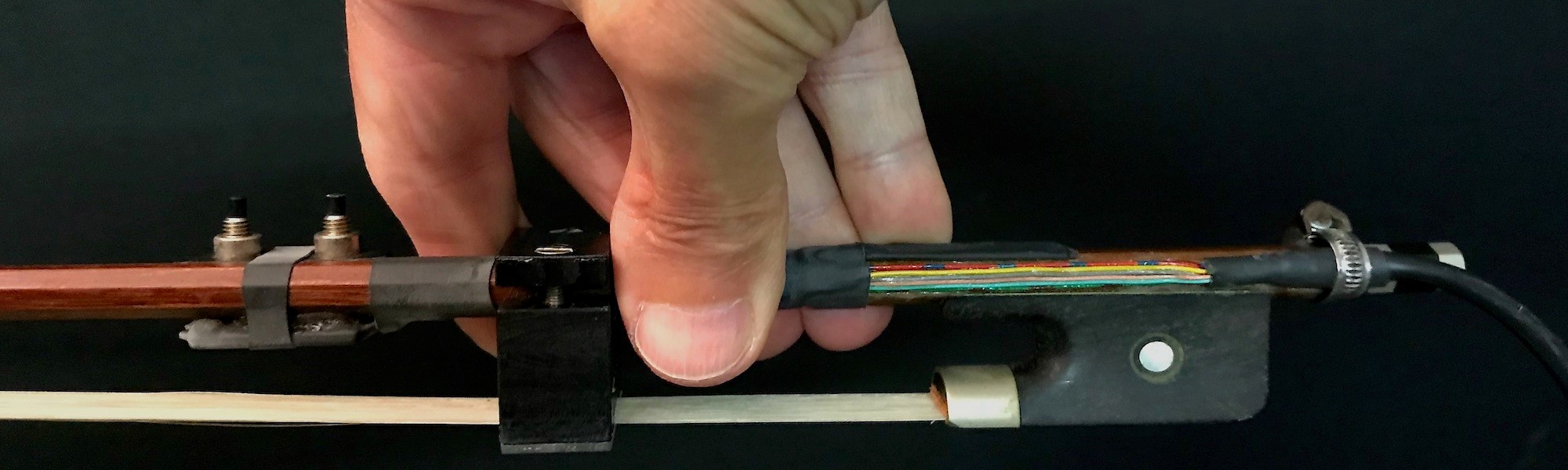

Most sonic objects that I have requisitioned are man made - fences, doors, chairs, fences, drainpipes, coffins, car wrecks, sports equipment, kitchen sinks, bicycles, plywood, corrugated iron - I notice DIY building materials are prevalent in the list. The list also refers to the time in which I live, I can't pick another time. (re-casting the function of the 500 year old violin was a given, it's what I was presented with at the age of seven). If I had been living pre-industrial revolution, I may have been more interested in pumping up sheep stomachs or harnessing the power of the local town windmill. And who did invent the all purpose wheel? But we are now post-industrial, so inevitably I have had to deal with binary, hence the interactive MIDI violin bow. But I notice in recent years, despite the wide ranging and joyful digital experiments, I have returned to the analogue physical world - the irreplaceable bones of music.

In traditional Aboriginal perception there is no such thing as an inanimate object; animal, vegetable, mineral are all connected to a living continuum. That rock, river, animal, and kinship experience of living may exist potentially in a mythical past or the every day present - or simultaneously in both. The object may lie in wait for the relevant song with which we humans will recognise that quality of livingness. There is also very little on this planet that does not make a sound when excited by bow, stick, wind, water, electricity, whatever. Living in Australia with its pre-curser of ancient indigenous musical instrument appropriations juxtaposed with its most recent flimsy white infrastructure actually makes some sense to me.

The plastic stuff comes from white fella culture, and even if useful, tends to be treated as outside of Aboriginal cosmology - ie. despite any utility, it is treated like trash, can never be anything more than trash.

Jon Rose June 2018

If you are a violinist, a string player of any instrument, or someone just interested in the why, how, and wherefore of music, I can thoroughly recommend a visit to Dr Rosenberg's Wunderkamer. This collection of over one thousand artefacts featuring everything on, with, or about violins, is the brain child of violinist, composer, improviser, and inventor Jon Rose. And not just your regular violins. In this museum are assembled violins of fantasy and the fantastic. There are violins with extra necks, violins with way too many strings, robot violins, wheeling violins, violins joined together like Siamese twins, violins to be played on and by a bicycle. Added to this are home made instruments and historic gems from the last 200 years There are violins made from metal drain pipes, plexiglass, vegetable boxes, 78 record players, and other unlikely materials and objects. There is a collection of now obsolete digital interactive violin bows. And by way of contrast is a vast assortment of kitsch with the violin featured in a kaleidoscope of everyday objects; a set of ten plastic clocks, book and album covers, telephones and telephone directories, schnapps bottles, stamp collections, playing cards, musical boxes, pencil sharpeners, fashionable ties, a door matt, jigsaw puzzles, shopping bags, cookie cutters, opium spoons, political badges, film posters - for example of Sherlock Holmes and of Charlie Chaplin playing the violin. There are countless postcards that depict romantic subjects with the ubiquitous violin - some sexually explicit. On the wall are nearly a hundred framed pictures of the violin often portrayed in some extremely weird situations.

Stringendo Magazine May 2018