SCORDATURA

or how to mistune the violin

The tour was going well and Veryan Weston and I arrived at a small club in Vienna to play the next concert. On stage was the piano tuner - he looked to be in an extremely bad mood. Our project Temperament requires that a small upright piano be tuned to Just C temperament. Normally it doesn't pose a problem as we can provide the exact pitches required, and these days most piano tuners use digital tuning devices. However, this piano tuner was adamant he would not do what we asked.

All my polite arguments about the history of temperament, the unsuitability of equal temperament for a piano and violin combination, the fact that equal temperament rendered all intervals out of tune - all of this fell on deaf ears. He informed me that he had spent his professional life tuning (stimmen) pianos; I was asking him to mistune (unstimmen) this instrument now before us. Never in his career had a musician asked him to perform such a perverse act. Eventually he retired to the bar across the road, returning reluctantly to mistune the piano after some hours of alcoholic fortification and the lure of a cash payment.

Scordatura means literally 'to mistune' although it generally refers to the mistuning of bowed string instruments such as violins, viola d'amore, and Hardanger fiddles. The idea of mistuning may also be a reductive and condescending view of history, as up to and including the 18th century there were so many options as to how string instruments might be tuned; it depended on the music and situation confronting a string player. There was no official method of tuning.

With regard to the popular or folk traditions, there is of course no documentation; all we have are the scores of the court composers who, as with the common dance forms, took much of their material and many of their ideas from the contemporary active aural tradition. It is not hard to find relationships between Celtic fiddle music and Biber.

Many years ago I had an uncomfortable epiphany when I realised that some passages of Bach were almost identical to some quite tacky versions of fiddle tunes that I was playing in a Country & Western Band as a hired hack. It took me some time to realise that both musics had a common source and that I was just being an elitist snob.

Biber, Schmelzer, and other violinist/composers of the day wrote stacks of music using scordatura to bring out the different sonorities offered by the violin. The Hardanger fiddle tradition (with the set of four sympathetics as well as the usual four bowable strings) is almost totally dedicated to sonority with no less than twenty scordatura tunings in common use today.

What is it with string players that they are never satisfied with the range and projection of their particular instrument (me too)? The double bass players always want to play higher, the violinists often yearn for those extra notes below G. Everyone wants to sound louder and to have their instrument more brilliant. It is not a new problem and there is no need for therapy from a professional guru.

A brief browse through the history of notated music reveals that Mozart wanted more life out of the viola in his Sinfonia Concertante and gave instructions for the instrument to be tuned a semitone higher. Berg got his cello players to tune down their C strings to play a B in the Lyric Suite. Mahler wanted the violin solo in his Fourth Symphony to sound more folksy and raucous, so it was tuned up a tone. In the previous century, the French deviant Baillot has a cadenza in his L'art du violon where the G-string is tuned downwards through semitones while playing - love that.

Then there is old Nicolo himself who, despite his fecund chops, wanted to get above the orchestra. The famous D major concerto was originally played by the orchestra in E-flat while Paganini played it, with his violin tuned a half step higher, in D. This is like the heavy metal guitarist turning his amp up to eleven.

You would never know it from the super straight violin culture that pervades classical music today, but the string tradition was always a restless and experimental paradigm. How many cellists know that Bach (or indeed Anna Magdalena Bach) intended the Fifth Cello Suite to be a scordatura piece with the A tuned down to a G?

Behold! Hollis Taylor has put together a veritable tour de force of scordatura. In the space of an hour she plays eight violins in nine different tunings. Now if a straight violin soloist changes violin in a concert, it is considered something of a catastrophe requiring months in an expensive Swiss sanitarium to recover. Ms. Taylor is doing the violin equivalent of climbing Mount Everest nine times without oxygen and with a guide who speaks in a different language at every attempt.

Hollis suffers from perfect pitch, which means that when she puts her first finger on the A string in first position she expects the note B perfectly in tune. If the A string is tuned to say F#, the result is a manic neuron panic which must be ignored. If you can put up with that, then scordatura offers intervals and chordal possibilities out of reach with the accepted G,D,A,E tuning.

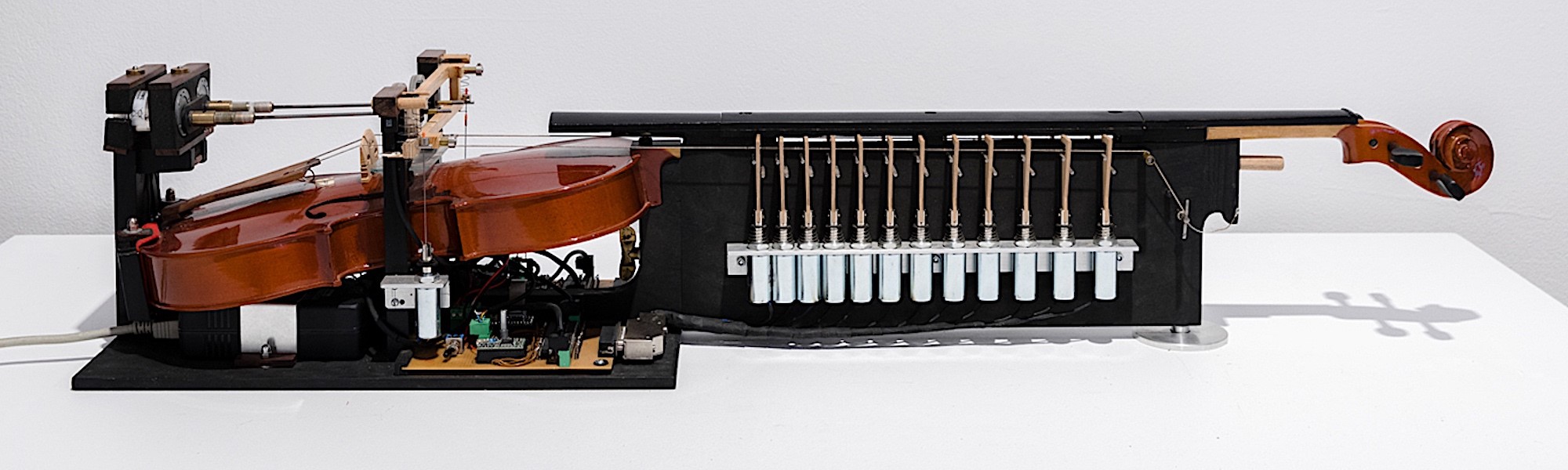

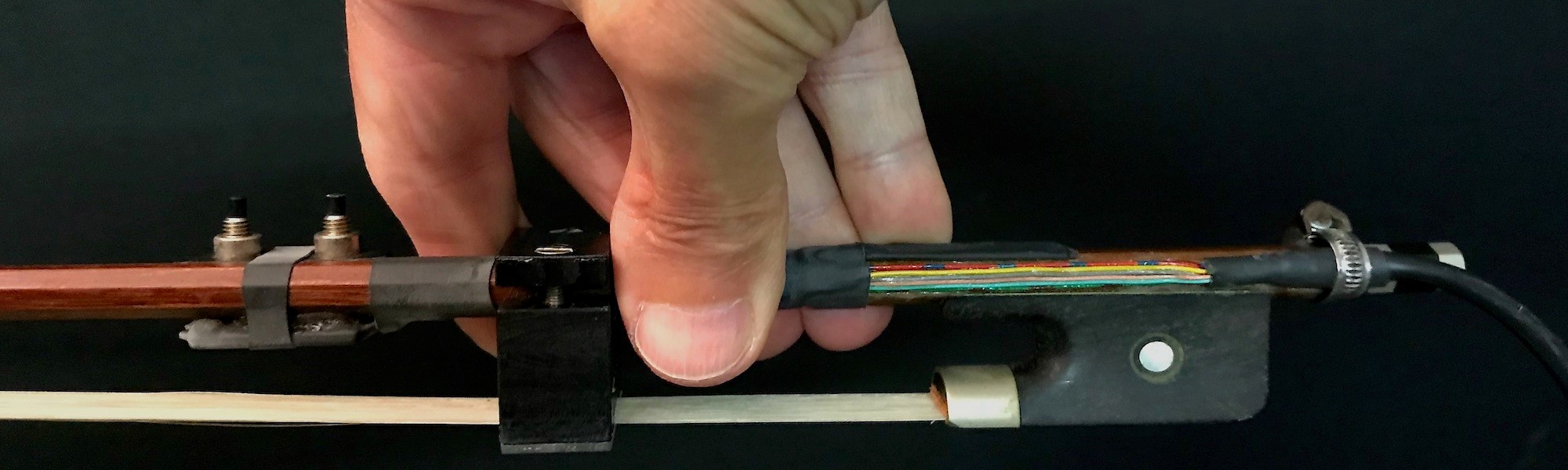

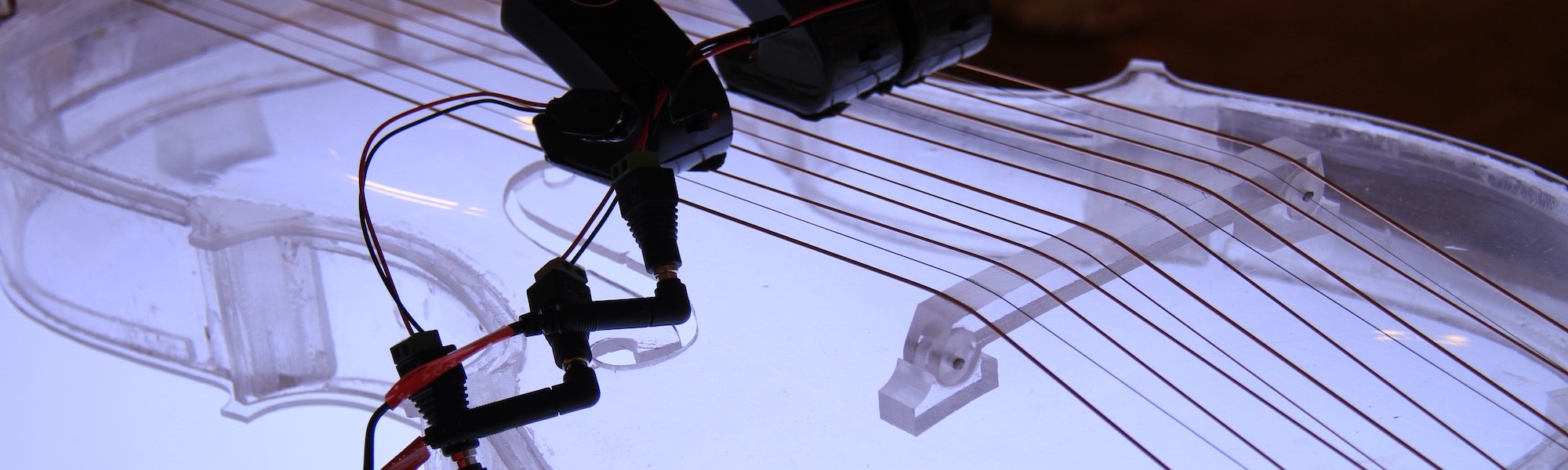

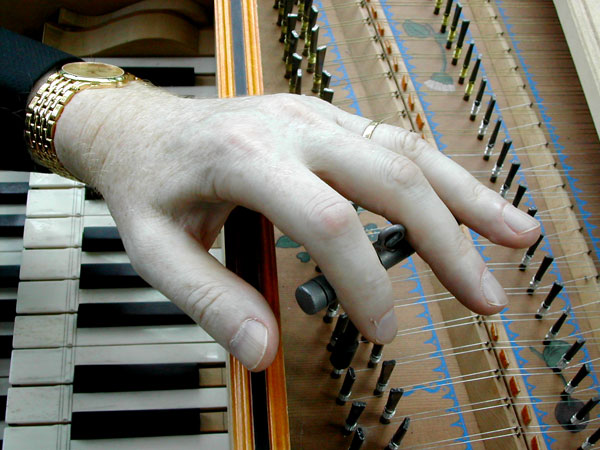

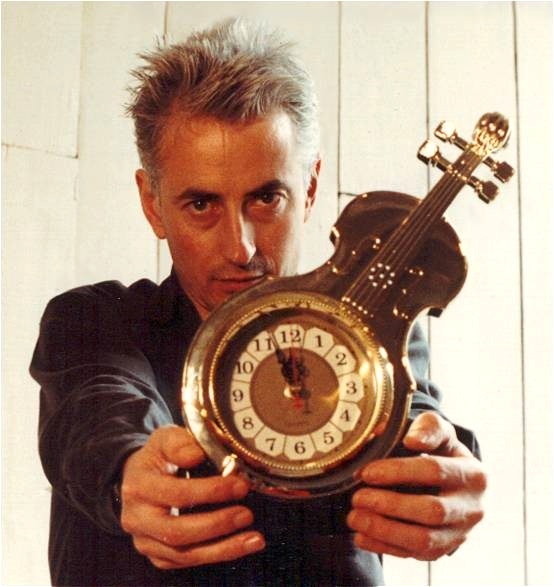

Her program presents aspects of scordatura from both vernacular and the classical traditions. You are listening to extracts from this program which was performed at the Melbourne International Arts Festival on 20/10/05 by Hollis Taylor - violins and David MacFarlane - harpsichord. David tunes his homemade harpsichord to the Tartini Temperament when playing with violinists - it ensures that at least the A-E interval is a perfect 5th. But having said that, it is the subtle differences in intonation between the instruments that present listener and player with such sonorous depth - and quite a wild ride when the music modulates. All the violins are modern instruments and, for the sake of Hollis' sanity, were kept at A=440. The five-string violin tuned in semitones, with a major third hanging off the end of it, is the ninth violin guest spot on the concert - performed by yours truly.

© Jon Rose 2005

The series featured American violinist Hollis Taylor in a feast of remarkable music, playing nine violins, all with different tunings. She performs plenty of Biber to show the value of Scordatura to Baroque composers, as well as her own arrangements and compositions. What really startled was Taylor's ability to move into various tuning situations without hesitation.

The Age 24/10/05